- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

Finite declarative complement clauses in Afrikaans prototypically take the form of a dependent clause embedded in a superordinate clause, usually called the main clause or matrix clause. This happens most frequently in a matrix clause with a subject and verb, to which the complement clause relates as an object clause, but declarative complement clauses can also be integrated as subject clauses or predicate clauses, as presented in the topic Finite Declarative complement clauses: Syntactic distribution.

The finite declarative complement clause completes the meaning of a verb in the higher clause, and there is in the prototypical case a relationship of semantic dependency of the complement clause on the matrix clause. The functionally subordinate status of finite complement clauses may be formally encoded by dependent word order, and marked by the presence of a complementiser.

Finite declarative complement clauses in standard Afrikaans take two construction forms: dat+[SXV] and Ø+[SVX]. The first construction form displays both markers of structural dependency: it includes the complementiser dat that, and uses verb-final dependent word order, in which all verbs occur in the final position. We refer to this construction as the dat+[SXV] construction.

If the verb phrase consists of a single past or present-tense lexical verb only, the verb occurs in the final position, as in (1) and (2). Combinations of auxiliary and lexical verbs are desribed below.

| Die ontwikkelaar sê dat die eenhede aansienlik minder kos. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) die ontwikkelaar sê [(CC) [(COMP) dat] [(SUB) die eenhede] [(ADV) aansienlik minder] [(VF) kos]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the developer say.PRS.PRS that.COMP the units considerably less cost.PRS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The developer says that the units cost considerably less. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Die ontwikkelaar sê dat die eenhede aansienlik goedkoper was. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) die ontwikkelaar sê [(CC) [(COMP) dat] [(SUB) die eenhede] [(ADJ) aansienlik goedkoper] [(VF) was]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the developer say.PRS that.COMP the units considerably cheaper be.PRT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The developer says that the units were considerably cheaper. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bosch (1999:12) points out that in spoken language, the complementiser dat may be replaced with laat/lat let, as in example (3) and (4), and Feinauer (1989:31) adds wat which as another possibility.

| "Ma' Oupa, hoekom sê onse mammas lat ons’ie aan hulle moet raak of hulle doodmaak'ie?" | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| but grandpa why say.PRS our mothers that.COMP we=not against them must.AUX.MOD touch.INF or them dead.make.INF=PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| "But Grandpa, why do our moms say that we shouldn't touch them or kill them?" | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| "Jy moet nou lat Kleinbooi en Hendrik vir jou leer rook, hoor!" | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| you must.AUX.MOD now that.COMP Kleinbooi and Hendrik for you teach.LINK smoke.INF hear.IMP | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| "You must now let Kleinbooi and Hendrik teach you to smoke, hear!" | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The construction with the complementiser and verb-final word order corresponds to the construction for finite declarative complement clauses in standard Dutch, which are obligatorily introduced by the complementiser dat that and followed by dependent verb-final word order (Biberauer 2002:32; Van Bogaert and Colleman 2013: 496). However, in Afrikaans, as in English, the complementiser may be omitted. If this is the case, word order in the complement clause reverts to independent verb-second order. We refer to this form as the Ø+[SVX] construction. This phenomenon also occurs to a limited extent in (spoken) German Auer (1998), Weinert (2012), and in – but in Afrikaans it is widespread, occurring in between a third and two thirds of all cases, depending on text type (Biberauer 2002:36, Van Rooy and Kruger 2016).

In this alternative construction for the finite declarative complement clause in Afrikaans, if there is a single past or present-tense lexical verb only, the verb occurs in the second position, as in (5) and (6). Combinations of auxiliary and lexical verbs are treated in Read More.

| Die ontwikkelaar sê die eenhede kos aansienlik minder. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) die ontwikkelaar sê [(CC) [(SUB) die eenhede] [(V2) kos] [(ADV) aansienlik minder]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the developer say.PRS the units cost.PRS considerably less | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The developer says the units cost considerably less. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Die ontwikkelaar sê die eenhede was aansienlik goedkoper. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) die ontwikkelaar sê [(CC) [(SUB) die eenhede] [(V2) was] [(ADJ) aansienlik goedkoper]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the developer say.PRS the units be.PRT considerably cheaper | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The developer says the units were considerably cheaper. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The choice between the two standard variants, dat+[SXV] and Ø+[SVX] is mainly an issue in object complement clauses. The verb of the main or matrix clause is the most important factor, with a number of high-frequency communication and mental verbs, such as sê to say, dink to think and weet to know usually taking the variant Ø+[SVX], while semantically more specific verbs (like meedeel to inform, eis to demand, bespiegel to speculate) and those that convey a causative meaning (like sorg to ensure, veroorsaak to cause) usually take the variant dat+[SXV]. Besides the verb of the matrix clause, first and second person singular pronoun subjects for this verb also increases the likelihood of the Ø+[SVX] variant, while inanimate third person subjects are more likely with the dat+[SXV] variant. Spoken language increases the likelihood of the Ø+[SVX] variant, while the more formal written registers are more likely to take the dat+[SXV] variant.

In addition to the two main structural variants, a third construction variant exists. In this variant, the complementiser dat that is present, but main-clause verb-second word order is used. We refer to this form as the dat+[SXV] construction. This construction, illustrated in (7) is regarded as non-standard, or a grammatical error (Steyn 1976:46; Olivier 1985:93-102; Feinauer 1989; Carstens 1989:70-72), but is nevertheless widespread in spoken language.

| Ek dink dat dit is vir my rêrig cool. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek dink [(CC) [(COMP) dat] [(SUB) dit] [(V2) is] [(PP) vir my] [(COMPLM) rêrig cool]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I think.PRS that.COMP it be.PRS for me really cool | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I think that to me it is really cool. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Biberauer (2002) finds that the non-standard dat+[SXV] form is associated with two conditions. Firstly, the matrix-clause verb is one of a limited set of high-frequency epistemic verbs: dink to think, sien to see, sê to say, weet to know, glo to believe and voel to feel account for more than 90% of instances of the non-standard dat+[SXV] form. Secondly, the verb occurring in the verb-second position is typically (in 84% of cases) a non-thematic verb (a copular, modal or auxiliary verb).

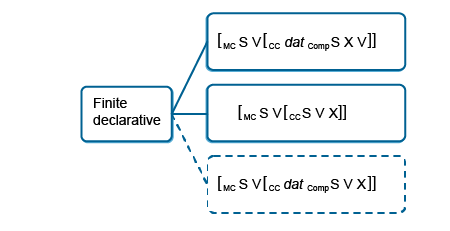

The three possible subconstructions for finite declarative clauses in Afrikaans are summarised in Figure 1, with the subconstruction perceived as non-standard indicated by dashed rather than solid lines.

- Introduction

- Word order in complement clauses with multiple verbs

- Topicalisation in complement clauses

- The alternation between the dat+[SXV] and Ø+[SVX] constructions: Frequency

- Factors that condition the choice between the dat+[SXV] and Ø+[SVX] constructions

- The development of Ø+[SVX]: Contrastive and historical data

- The dat+[SVX] construction

Variation in the form of the finite declarative complement clause is mainly encountered in the object clause use, and therefore the discussion will focus on the object clause use only. When used as a subject clause or predicate clause, the finite declarative complement clause almost always takes the form dat+[SXV]. If a finite declarative complement clause functions as subject clause, dat+[SXV] is obligatory, as illustrated in (8a), with (8a') judged ungrammatical.

More detail on the limited use of the Ø+[SVX] construction beyond the object clause use is provided in Finite declarative complement clauses: Syntactic distribution. In the following Read More sections, further word order options within finite declarative complement clauses are discussed first: word order variation in declarative complement clauses with multiple verbs, and the limited occurrence of topicalisation in finite declarative complement clauses. Thereafter, the frequency of the two standard variants, dat+[SXV] and Ø+[SVX], and factors related to the choice between the variants are discussed, before their historical development is considered. Finally, more detail about the non-standard variant dat+[SXV] is presented, including frequency, factors that correlate with its occurrence, and its historical development.

In the Quick Info, the word order in complement clauses with a single lexical verb was presented in (1) and (2) for the variant dat+[SXV], and in example (5) and (6) for the variant Ø+[SVX]. If the main verb is accompanied by a modal auxiliary in the variant dat+[SXV], the modal verb occurs directly before the main verb, as in (9). The same holds for any aspectual verbs accompanying the main verb, as in (10).

| Die ontwikkelaar sê dat die eenhede aansienlik minder kan kos. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) die ontwikkelaar sê [(CC) [(COMP) dat] [(SUB) die eenhede] [(ADV) aansienlik minder] [(VF) kan kos]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the developer say.PRS that.COMP the units considerably less can.AUX.MOD cost.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The developer says that the units could cost considerably less. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Die ontwikkelaar sê dat die eenhede nou aansienlik minder begin kos. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) die ontwikkelaar sê [(CC) [(COMP) dat] [(SUB) die eenhede] [(ADV) nou aansienlik minder] [(VF) begin kos]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the developer say.PRS that.COMP the units now considerably less start.LINK cost.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The developer says that the units are now starting to cost considerably less. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In past-tense constructions formed with the auxiliary het have, the auxiliary always occurs after the main verb in the past-participle form, as in (11) and (12).

| Die ontwikkelaar sê dat die eenhede aansienlik minder gekos het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) die ontwikkelaar sê [(CC) [(COMP) dat] [(SUB) die eenhede] [(ADV) aansienlik minder] [(VF gekos het]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the developer say.PRS that.COMP the units considerably less cost.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The developer says that the units cost considerably less. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Die ontwikkelaar sê dat die eenhede aansienlik minder kon gekos het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) die ontwikkelaar sê [(CC) [(COMP) dat] [(SUB) die eenhede] [(ADV) aansienlik minder] [(VF) kon gekos het]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the developer say.PRS that.COMP the units considerably less can.AUX.MOD.PRT cost.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The developer says that the units could have cost considerably less. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the other construction form, Ø+[SVX], an auxiliary is found in the second position, with the main verb and other auxiliaries in the clause-final position. If the main verb is only accompanied by a modal auxiliary, the modal verb takes the verb-second position, and the main verb is in the final position, as in (13). The same holds for any aspectual verbs accompanying the main verb, shown in (14).

| Die ontwikkelaar sê die eenhede kan aansienlik minder kos. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) die ontwikkelaar sê [(CC) [(SUB) die eenhede] [(V2) kan] [(ADV) aansienlik minder] [(VF) kos]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the developer say.PRS the units can.AUX.MOD considerably less cost.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The developer says the units could cost considerably less. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Die ontwikkelaar sê die eenhede begin nou aansienlik minder kos. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) die ontwikkelaar sê [(CC) [(SUB) die eenhede] [(V2) begin] [(ADV) nou aansienlik minder] [(VF) kos]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the developer say.PRS the units start.LINK now considerably less cost.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The developer says the units are now starting to cost considerably less. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In past-tense constructions formed with the auxiliary het have, the auxiliary occurs in the second position, with the past-participle form of the lexical verb in last position, as in (15). If a modal verb is present in addition, the modal verb occurs in the second position, with the past-tense auxiliary verb in the final position, preceded by the lexical verb, as in (16).

| Die ontwikkelaar sê die eenhede het aansienlik minder gekos. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) die ontwikkelaar sê [(CC) [(SUB) die eenhede] [(V2) het] [(ADV) aansienlik minder] [(VF) gekos]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the developer say.PRS the units have.AUX considerably less cost.PST | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The developer says the units cost considerably less. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Die ontwikkelaar sê die eenhede kon aansienlik minder gekos het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) die ontwikkelaar sê [(CC) [[(SUB) die eenhede] [(V2) kon] [(ADV) aansienlik minder] [(VF) gekos het]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the developer say.PRS the units can.AUX.MOD.PRT considerably less cost.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The developer says the units could have cost considerably less. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In complement clauses introduced by the complementiser dat that, non-subject elements (adverbials or topicalised elements) are barred from occurring in the initial position (Biberauer 2002:34), as shown in (17a) and (17b).

In Biberauer's (2002) corpus of written Afrikaans, topicalised elements do not occur at all in dat+[SXV] constructions. Adverbials occur in first position around 5% of the time in written Afrikaans, but these are all adverbial clauses that are consistently and obligatorily of the interpolative type(Biberauer 2002:34), as in (18).

| Hy glo dat, as die span positief voel, hulle enige iemand kan klop. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| he believe.PRS that.COMP if the team positive feel.PRS they any somebody can.AUX.MOD beat.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| He believes that, if the team feel positive, they can beat anyone. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Biberauer (2002:34) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Biberauer (2002:33) points out that the Ø+[SVX] construction theoretically allows a variety of first-position elements, unlike the dat+[SXV] construction. Sentences like (19a) (with the adverbial in initial position) and (19b) (with the object in initial position) are therefore acceptable.

However, in practice topicalised elements as well as adverbials are very infrequent in Ø+[SVX] constructions in contemporary Afrikaans. In Biberauer's (2002:33) data, adverbials occur in less than 3% of Ø+[SVX] clauses in modern written Afrikaans, and topicalised elements do not occur at all. Where adverbials do occur, they typically occur in an adjunction structure, as in (20) (from Biberauer 2002:33).

| Ek weet, as hy kom, gaan ons lekker partytjie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I know.PRS if he come.PRS go.PRS we nicely party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I know, if he comes, we are going to have a ball. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Biberauer (2002:33) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Generally there are no prescriptive restrictions on the dat+[SXV] and Ø+[SVX] forms. According to Stell (2011:175), it is mentioned by early standardisers, but with no proscription, and current normative sources do not prescribe the use of one form rather than the other.

There has been little comprehensive research on the frequency of dat+[SXV] and Ø+[SVX] in Afrikaans until recently. Among earlier research, Malherbe (1966:13) points out that in spoken Afrikaans, Ø+[SVX] is prevalent, while in written language dat+[SXV] and Ø+[SVX] forms occur with equal frequency. While Ponelis (1979:440-441) classifies the omission of dat that as a less common strategy, he also points out that in written as well as spoken language, unmarked subordinate clauses are well established and very common. Similarly, Feinauer (1990:117) comments on the frequency of Ø+[SVX] in both written and spoken language. There are some remarks on regional differences: Steyn (1976:18) observes that in the speech of rural white speakers of Afrikaans dat that occurs much less frequently, and the Ø+[SVX] form is the most frequent.

There are a few recent studies that quantify the frequency of the alternation between the two forms. Biberauer's (2002) analysis of a 80,000 word corpus of modern written Afrikaans from newspapers and magazines finds that the Ø+[SVX] construction occurs at a rate of 37%, a rate which is very similar for her 80,000 word corpus of early written Afrikaans composed of letters, diaries, newspaper columns, and novel extracts dating from 1887 to 1923, where the rate is 35% (Biberauer 2002:31-32). In a comprehensive corpus analysis of 104 verb lemmas that control finite declarative complement clauses, using the Taalkomissiekorpus of around 57 million words of written, published Afrikaans, Van Rooy and Kruger (2016) find an occurrence rate of 67% for Ø+[SVX]. Colleman et al. (2016) report an occurrence of 56% for Ø+[SVX] in their analysis of a newspaper corpus of more than 6 million words.

In contemporary spoken Afrikaans the frequency of Ø+[SVX] is 46%, based on a corpus of 80,000 words of interview and television and radio broadcast data (Biberauer 2002:36). Stell (2011) analysed a limited set of high-frequency verbs typically associated with Ø+[SVX] (dink to think, glo to believe, hoop to hope, hoor to hear, sê to say, verstaan to understand, vertel to tell, weet to know and wens to wish), using a 415,000-word corpus consisting of different varieties of spoken Afrikaans, across different age cohorts. He finds that with these verbs the Ø+[SVX] form is selected between 70% and 100% of the time, and argues that the Ø+[SVX] form is becoming more generalised, across different varieties. For most groups, the rate of Ø+[SVX] is above 90%. Contrasts only exist in older age cohorts, with the Namibian Afrikaans samples as well as the sample of Afrikaans from northern, white, urban speakers demonstrating a comparably more limited preference for the Ø+[SVX] form (Stell 2011:175).

The choice between the two standard forms of the finite declarative complement clause in Afrikaans is conditioned by a number of lexicogrammatical and discourse factors. The choice between the two constructions is, in the first instance, lexically conditioned, in that some verbs demonstrate a distinct preference for the dat+[SXV] form, while others prefer the Ø+[SVX] construction (Braeckeveldt 2013, Colleman et al. 2016, Van Rooy and Kruger 2016).

Van Rooy and Kruger (2016) find that the following verbs do not allow Ø+[SVX] at all: aanstip to note, aframmel to rattle off, agiteer to agitate, antisipeer to anticipate, bepleit to plead, bluf to bluff, deklameer to declaim, deursein to signal through, dikteer to dictate, gewaar to notice, herbeklemtoon to re-emphasise, herbevestig to reconfirm, konkludeer to conclude, konstateer to state, neul to nag, ontgaan to escape, paai to placate, postuleer to postulate, profeteer to prophesy, propageer to propagate, rondvertel to blab, stateer to state, teëkap to retort, teoretiseer to theorise, terugskryf to write back, verifieer to verify, verordineer to ordain, volg to follow and wink to beckon.

They also report a set of verbs with very low percentages of Ø+[SVX], which are the following, with the percentage that occurs without the complementiser in brackets: vind to find (10), vra to ask (10), argumenteer to argue (6), bemerk to notice (6), spekuleer to speculate (6), afspreek to agree (6), verswyg to withhold (5), beveel to command (4), aanbeveel to recommend (4), stipuleer to stipulate (3).

Verbs that do not allow omission, or generally prefer the full form, tend to be more formal, low-frequency verbs, with a higher incidence of communication verbs. Braeckeveldt (2013) lists more verbs that strongly prefer the dat+[SXV] construction, to the extent that the alternative is felt to be ungrammatical and hardly ever occurs, including sorg to ensure, veroorsaak to cause and eis to demand.

The alternations in (21), (22) and (23) demonstrate the unacceptability of the Ø+[SVX] construction with these verbs.

These verbs, where the Ø+[SVX] form is felt to be unnatural or even ungrammatical, form a distinct group of verbs within the general class of verbs that control complement clauses, as discussed in more detail in Finite declarative complement clauses: Lexical and semantic associations. Most of the verbs that control complement clauses entail what Dor (2005), in his research on that-deletion in English, terms a truth claim: (Dor 2005:345). Complement-controlling verbs that involve this semantic entailment allow the deletion of the complementiser. Conversely, verbs that do not have this entailment generally disallow the omission of the complementiser. The verbs in (21), (22) and (23) do not meet this requirement, and it appears that many Afrikaans verbs which strongly disfavour the Ø+[SVX] construction share the feature of non-entailment of a truth claim. A very salient subset among these verbs is causative verbs, which are used with a complementiser most of the time (Colleman et al. 2016).

For other verbs, it is less a case that the Ø+[SVX] form is judged unnatural or ungrammatical, but simply a case that the dat+[SXV] form occurs more frequently with these verbs than the Ø+[SVX] form does. Van Rooy and Kruger (2016), for example, find that verbs like postuleer to postulate, argumenteer to argue and vind to find occur infrequently with the Ø+[SVX] – despite the fact that these verbs do semantically entail a truth claim by a cognitive agent and the Ø+[SVX] form is acceptable. The alternations with these three verbs are illustrated in (24), (25) and (26). Despite the fact that the second Ø+[SVX] example in each pair is not unacceptable, it is simply extremely unlikely to occur.

Feinauer (1990:117) proposes that the omission of dat that has the effect of placing greater emphasis on the semantic content of the embedded clause. Consequently the omission of dat that typically takes place after a main clause that is semantically less dominant (Feinauer 1990:117). This means that the Ø+[SVX] form is more likely to occur after a matrix verb that is semantically more neutral (e.g. sê to say) than one which is not (e.g. stamel to stammer). The Ø+[SVX] form after semantically specific verbs is not generally viewed as grammatically unacceptable, but is less common. According to Dor (2005:348), “manner of speaking” predicates do not semantically entail a truth claim, but may be pragmatically extended to imply such a claim. For this reason, language users have more ambiguous judgements about the acceptability of the zero form with such verbs – which results in a lower frequency of the zero form with semantically rich verbs like these. Example (27) illustrates this with the verb mor to grumble – which only occurs with dat+[SXV] in the Taalkomissiekorpus.

In this analysis, the semantic richness of a verb like mor to grumble (further emphasised by the adverbial al lank for a long time) of necessity correlates with a semantic emphasis on the main clause, with the complement clause completing the meaning of the semantically dominant main verb. This prototypical relationship of subordination between main and complement clause is marked by the preference for dat+[SXV]. While the Ø+[SVX] form in (27a') is not grammatically incorrect, the use of the main-clause word order and the absence of the complementiser, which shifts the emphasis to the complement clause, is at odds with the discourse centrality implied by the semantic richness of the main-clause verb – which is most likely why the Ø+[SVX] form does not occur with mor to grumble.

On the other side of the spectrum, there are verbs that occur more frequently with the Ø+[SVX] form than with the dat+[SXV] form. Verbs with the strongest preference for the Ø+[SVX] form (as indicated by the percentage of occurrence in brackets) are the following: sê to say (90), dink to think (86), wed to bet (82), wens to wish (82), weet to know (68), hoor to hear (66), voel to feel (65), wis to know (63), afkondig to announce (63), and skat to guess/estimate (61). With some exceptions, these verbs tend to be high-frequency mental verbs.

While both forms are equally acceptable with these verbs (as shown in (28), (29) and (30)) the Ø+[SVX] form is much more frequent, for these three verbs, for example, Van Rooy and Kruger (2016) show that it is selected more than 80% of the time).

Braeckeveldt (2013:45) observes that the verbs preferring Ø+[SVX] tend to be morphologically simple, are usually semantically general rather than specific and are more informal, in contrast to the verbs preferring dat +[SXV], which tend to me more formal and morphologically complex.

In addition to the collocational preferences of particular main-clause verbs (see also Colleman et al. 2016, Van Rooy and Kruger 2016) demonstrate that three main factors predict the choice between dat+[SXV] and Ø+[SVX] in Afrikaans. The first factor is the frequency of the matrix verb, with high-frequency verbs favouring Ø+[SVX]. Within the group of high-frequency verbs, a second factor comes into play, namely the semantics of the matrix verb. Matrix verbs that are not mental verbs expressing a truth claim prefer the dat+[SXV] form most of the time, leading to the conclusion that non-epistemic verbs favour the overt form. The last factor is register: for mental verbs expressing a truth claim, more formal registers prefer dat+[SXV], whereas the others prefer Ø+[SVX] in the study of Van Rooy and Kruger 2016. In earlier research, Malherbe (1966:14) also touches on issues of register, pointing out that the omission of the complementiser is less likely in formal texts, and more frequent in texts where the intention is to create a colloquial style. Based on the higher frequency of Ø+[SVX] in spoken than in written Afrikaans, Biberauer (2002:36) identifies a register effect, but also argues that the high omission rate even in written Afrikaans means that Ø+[SVX] in Afrikaans is not just the supposedly informal, spoken-language feature it is assumed to be in English (Biberauer 2002:34).

These factors correspond to many of the factors that have been shown to condition the alternation between the form with and without the complementiser in English (Thompson and Mulac 1991; Biber 1999; Dor 2005; Tagliamonte and Smith 2005; Boye and Harder 2007; Kearns 2007; Torres Cacoullos and Walker 2009; Dehé and Wichmann 2010; McGregor 2013).

Until recently, there has been little systematic investigation of the factors that condition the choice of the dat+[SXV] and Ø+[SVX] constructions in Afrikaans, with some, like Malherbe (1966:15) describing this choice as more or less random. However, in his study, he nevertheless proposed a number of factors that may be relevant, which more recent corpus investigations support. Malherbe (1966:13) observes that the omission of dat most frequently occurs after “werkwoorde wat gewoonlik basiese menslike gevoelens of basiese waarnemings van die menslike sintuie uitdruk”. Specifically, he lists the following verbs where omission of dat is attested: belowe to promise, besef to realise, beteken to mean, beweer to claim, bewys to prove, dink to think, droom to dream, help to help, hoor to hear, onthou to remember, reken to reckon, skat to guess, sweer to swear, toon to demonstrate, uitvind to find out, verbeel to imagine, verdra to tolerate, verneem to gather, verwag to expect, vind to find, voel to feel and weet to know (see also Donaldson 1993:314-315). These verbs typically occur together with a pronoun as subject in the main clause – often ek I, and Malherbe (1966:13) suggests that it is particularly in this collocational environment that the omission of datthat has become all but fixed. Feinauer (1990:118) argues that it is the combination of these general verbs of perception and feeling with pronominal subjects that contribute to the “low semantic value” of the matrix clause, leading to a reduced information focus on the matrix clause in favour of increased emphasis on the complement clause – formally expressed in the Ø+[SVX] form.

Malherbe raises other diverse factors that appear to play a role in conditioning the use of the Ø+[SVX] form in Afrikaans. He mentions that the form without dat that in reported speech may be preferred because it does not require adjustment of the word order, and may thus be easier for some speakers (Malherbe 1966:13). Stylistically, dat that may be omitted for purposes of emphasis (Malherbe 1966:14), which in spoken language is followed by a pause, and in written language by a colon or dash (see also Bosch 1999:11). Lastly, he refers to a number of syntactic constructions in which omission is either avoided, or more common (Malherbe 1966:14-16), some of which may be related to complexity factors.

According to a number of scholars, Standard Dutch does not allow the Ø+[SVX] construction (Biberauer 2002:32, Van Bogaert and Colleman 2013:496). However, both Lubbe (1983) and Feinauer (1990) point out that examples of this usage have been recorded. Feinauer (1990:118) cites the examples in (31), (32), (33) and (34), from data in Geerts et al. (1984:928) and Den Hertog (1973:57,67).

| Het spijt me ik kan niets voor u doen. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it cause.regret.PRS me I can/AUX.MOD nothing for you do.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I regret I can do nothing for you. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| U zult zien dat is niet zo moeilijk. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| you will.AUX.MOD see.INF that be.PRS not so difficult | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| You will see it is not that difficult. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik wil het niet verhelen, die onderneming heb ik nooit vertrouwd. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I want.to.AUX.MOD it not conceal.INF that business have.AUX I never trust.PST.PTCP | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I won't hide it, I never trusted that business. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Het valt niet te ontkennen zijn houding is in the laatste tijd aanmerkelijk veranderd. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it fall.PRS not PTCL.INF deny.INF his attitude be.PRS in the recent time noticeably change.PST.PTCP | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It cannot be denied his attitude changed noticeably in recent times. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In addition, Dutch recognises an intermediate category of semi-direct reported speech, which takes the Ø+[SVX] form. Semi-direct reported speech is a category in between direct reported speech and indirect reported speech. It differs from indirect reported speech in that the quote has the form of a main clause. In this analysis, the complementiser is obligatory in indirect reported speech constructions with declarative quotes, but cannot be used in semi-direct reported speech constructions. Semi-direct reported speech is illustrated in (35b), in comparison with indirect reported speech, in (35a).

In this interpretation, the Ø+[SVX] form is a special, limited subset of reported speech in Dutch, and not a generalisable pattern that extends to complement clauses more broadly. The consensus appears that the construction is very infrequent and highly marked in Dutch.

The high frequency of the construction in Afrikaans therefore raises questions about the factors that account for this divergence between Afrikaans and Dutch. Most scholars point to the fact that Afrikaans had been in contact with English for more than 100 years before standardisation as an important factor (Biberauer 2002:32). However, Donaldson (1988:277) and Stell (2011:174) argue that the omission of the complementiser can, in fact, be traced back to Middle Dutch. Feinauer (1990:118) demonstrates that constructions without the complementiser are present in eighteenth-century Afrikaans Dutch, in a limited way, becoming more widespread in nineteenth-century Afrikaans. Steyn (1989:24-25) and Van der Merwe (1960:55) additionally point to a tendency in some forms of Settler Dutch to omit the complementiser after illocutionary verbs like sê to say(Steyn 1989:24-25). In other words, the form without the complementiser may in the first instance have been introduced into eighteenth-century Afrikaans-Dutch from the input varieties while contact with English, in the second instance, may account for the extension of the construction to other verbs and the rapid dissemination of the feature (Feinauer 1990:119, Ponelis 1979:242, Donaldson 1988:279). In addition, Malherbe (1966:13) raises the possibility that the development of the Ø+[SVX] construction may have been reinforced by the greater cognitive ease and availability associated with the main-clause form. In spoken language particularly, speakers may be more prone to stringing together coordinated clauses, rather than opting for subordinated clauses.

Using Kirsten's (2016) twentieth-century Afrikaans Historical Corpus, we examined the distribution of the two variants for the ten most frequent verbs. The corpus consists of 250,000 words for each of the decades 1911-1920, 1941-1950, and 1971-1980. A total of about 400 complement clauses were extracted for each decade, and these numbers were compared to the values for the corresponding verbs in the Taalkommissiekorpus. The results show relative stability in the early and middle parts of the century, with ommission rates at 35% and 28%, but then omission increases sharply to 45% by the 1970s, and even further to 72% for these ten verbs in the corpus of contemporary Afrikaans (thus slightly higher than the 67% found by Van Rooy and Kruger (2016).

The use of the complementiser dat that with verb-second main-clause word order in the complement clause is proscribed by normative sources, and is generally viewed as a grammatical error that is the consequence of English influence (Carstens 2003:42-53; Prinsloo and Odendal 1995; Van der Merwe 1967). Despite proscriptions on dat+[SVX], it occurs widely (Steyn 1976:46; Conradie 2004:160), and is particularly associated with spoken language. It also occurs with the colloquial variants of dat that: lat that/let, laat let and wat which(Feinauer 1990:31), as in (36).

| Hulle vertel my lat hier annerkant op Kraandraai het nou laasjaar 'n meisietjeent weggeraak. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| they tell.PRS me that.COMP here other.side on Kraandraai have.AUX now last.year a girl.child away.get.PST | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| They tell me that over there in Kraandraai a girl went missing. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Estimations of the frequency of the construction vary widely. Research on the extent to which this variant occurs agrees on the finding that it is almost absent from the written language, with the exception of Lubbe (1983:99), who claims that the phenomenon is not restricted to the spoken language but occurs widely selfs by persone wat hulle moedertaal goed beheers (even among people with good command of their native tongue). Lubbe (1983:100) offers textual examples of the occurrence of dat+[SVX] in late nineteenth-century Transvaal newspapers as well, but he offers no quantification of the data. According to Biberauer (2002:39), in her corpus of contemporary spoken Afrikaans, about 41% of complement clauses with dat that occur with main clause verb-second word order. Feinauer (1987) and (1989) reports a frequency of 18% for this word order in her data, while Olivier (1985:101) claims that 50% of the examples in her spoken corpus have this word order. Stell (2011:180) demonstrates that the probability of dat+[SVX] is much higher for coloured speakers of Afrikaans (south-western, Namibian and north-western), at around 33%, than for white speakers (northern white urban: 17%, northern white rural: 15%, southern white: 5%, Namibian white: 7%). He further finds increasing divergence between the two groups regarding this feature, with an increase among coloured speakers and a decline among white speakers across different age cohorts.

There are a number of factors that appear to correlate with the use of the to construction. Biberauer (2002:42) suggests that when an often lengthy parenthetical adverbial clause is in the first position in the complement clause, preceded by dat that, the main-clause verb-second word order is more common because of an anacoluthon effect – a syntactic discontinuity because of the interruption of the adverbial clause, as in (37). It is likely that the interruption of the adverbial clause leads to a construal of the complement clause as a main clause.

| Die reëls bepaal dat, as daar nie 'n botsing tussen die bote is nie, kan daar nie 'n diskwalifikasie wees nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the rules determinePRS that.COMP if there not a collision between the boats be.PRS PTCL.NEG can.AUX.MOD there not a disqualification be.INF PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The rules determine that, if there is not a collision between the boats, there cannot be a disqualification. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Biberauer (2002:41) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Furthermore, the majority of the verbs (84%) occurring in second position in the complement clause in dat+[SVX] constructions are nonthematic or functional verbs, including the copular verb is to be, modals like moet must, and the auxiliary het have. Where lexical verbs do occur, they tend to be restricted to high-frequency verbs.

Lastly, the semantics of the matrix-clause verb also plays a role. In spoken Afrikaans, the high-frequency epistemic verbs dink to think, sien to see, sê to say, weet to know, glo to believe and voel to feel account for more than 90% of instances of dat+[SVX](Biberauer 2002:43, see also Stell 2011:182).

As far as the development of the dat+[SVX] form is concerned, it should be noted that the tendency to use main-clause word order in dependent clauses is not restricted to finite declarative complement clauses, but also occurs after other subordinators, like omdat because, in interrogative complement clauses, and in relative clauses, particularly after wat which(Feinauer 1989:30, Biberauer 2002). It is particularly widespread in specific interrogative complement clauses(Biberauer 2002).

The non-standard use of verb-second word order in dependent clauses more generally is widely ascribed to the influence of English (Carstens 2003:42-43, Ponelis 1993:341-342, Steyn 1976:47-48). A number of scholars, however, point to other factors that may be at the root of the phenomenon, with contact with English accelerating its diffusion.

Feinauer (1989:32-33) posits that the main-clause word order occurs so frequently after dat that as a consequence of the fact that it is semantically neutral, and is not strongly associated with subordination. As a consequence, for many language users, the boundaries between coordination and subordination are not very distinctly cognitively represented in compound sentences formed with dat that. She cites the fact that dat that can often be replaced with the coordinating conjunctions maar but and en and, as shown in (38) and (39) (from Feinauer 1989:32) as support for the diffuse status of dat that. Steyn (1976: 48) adds ja yes as another replacement for dat that, as in (40) (from Steyn 1976:48).

Because speakers do not perceive a clear distinction between coordination and subordination, they therefore also do not select the normatively expected construction – leading to the use of the dat+[SVX] form (Feinauer 1990:33). In addition, in spoken language there is a processing constraint imposed by time pressure, which leaves the speaker with too little time to make a decision about the appropriate word order, causing her to revert to the default main-clause word order (Feinauer 1990:33). The use of the complementiser dat that, in itself, may be a filler strategy to buy time for cognitive processing – after which the speaker may no longer keep track of the fact that what follows is supposed to be a dependent clause, and simply treats the complement clause as if it were a main clause (Steyn 1976:48).

In terms of the historical development of dat+[SVX] many scholars point to the influence of English, but other factors also appear to have played a role. According to Feinauer (1989:33-34), the dat+[SVX] form also occurs in Dutch and German. It is attested as far back as the Hildebrandslied (Old High German), shown in (41) (Schneider 1938:56, cited in Feinauer 1989:34).

| "… dat Hiltibrant haetti min fater." | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| COMP Hiltibrant be.call.PST my father | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| '...that Hiltibrand was called my father " | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Schneider (1938:56), cited in Feinauer (1989:34) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In Old High German as well as Middle Dutch SVX word order sometimes occurs in dependent clauses, and Gerritsen (1980:125) argues that subordinate clauses in Middle Dutch could also have SVX placement (and frequently did), instead of the SXV-only placement of modern Dutch – based on an analysis of Het Limburgse leven van Jezus (1275).

Feinauer (1989) shows that dat+[SVX] form occurs in a limited way in early eighteenth-century written Afrikaans-Dutch. It increases over time to a frequency of around 20% in modern spoken Afrikaans, which she ascribes to the influence of English. Steyn (1989:25) also raises the possibility of English influence, but points out the presence of the Ø+[SVX] form in early Afrikaans-Dutch. He suggests that as part of the processes of standardisation in Afrikaans, the use of dat that may have increased, but that by that time the SVX word order associated with the zero form (and with main clauses) had become so entrenched that the word-order implications of the reintroduction of the complementiser were not perceived by all speakers.

Of course, it may well be that dat+[SVX] was more common in the earlier spoken forms of Afrikaans as well, of which there are no records. Furthermore, Den Besten (2012:287) argues that SVX and VSX word order would have existed as competing forms from the earliest stages of Cape Dutch, because of competing substrates – the Khoi SXV substrate and the SVX Creole Portuguese and Malay substrates. Stell (2007:112-113) finds evidence for this claim in the fact that SVX word order in dependent clauses is widespread in Cape Malay manuscripts from the late-nineteenth century, the variety most influenced by these substrates and least influenced by the normative conventions of Dutch.

Biberauer (2002:39), however, finds a very low frequency (less than 3%) for the dat+[SVX] form in her corpus of early Afrikaans letters, diaries, newspaper articles and novel extracts from 1887-1923 – a frequency that is very similar to the rate in modern written Afrikaans. She argues that her pre-standardisation corpus closely reflects spoken Afrikaans, and based on this, she argues that the high frequency of dat+[SVX] in contemporary spoken Afrikaans cannot be seen as a feature that has always been present in spoken Afrikaans. Rather, she argues, it is an innovation of contemporary spoken Afrikaans (Biberauer 2002:39).

A number of scholars raise the question of whether the dat+[SVX] form constitutes an instance of ongoing language change. Feinauer's (1989) argument is that it does not, because speakers never consistently shift to this construction – instead it always exists in alternation with the normative dat+[SXV] construction – even in the same utterance. She also argues that the increases in frequency of the dat+[SXV] form do not provide sufficient evidence of the ascendancy of this form to the degree that it replaces the normative construction. Biberauer (2002) suggests otherwise, arguing that dat+[SXV] (together with the widespread use of main-clause verb order in wh-interrogative clauses) is an innovation in contemporary spoken Afrikaans that is gaining ground, resulting in a process of linguistic change which may superficially alter the embedded V2 characteristics of the language (Biberauer 2002:48).

- 1998Zwischen Parataxe und Hypotaxe: “Abhängige Hauptsätze” im gesprochenen und geschriebenen DeutschZeitschrift für Germanistische Linguistik26(3)284-307

- 1999A register perspective on grammar and discourse: Variability in the form and use of English complement clausesDiscourse Studies1(2)131-150

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Bundels

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: Is this a unitary phenomenon?Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics3419-69

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: Is this a unitary phenomenon?Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics3419-69

- 1999Die onderskikker 'dat': 'n korpus-gebaseerde bespreking (Deel 2).South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde172-15,

- 1999Die onderskikker 'dat': 'n korpus-gebaseerde bespreking (Deel 2).South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde172-15,

- 2007Complement-taking predicates: Usage and linguistic structureStudies in Language31(3)569-606

- 2013De skoon bysin in Afrikaanse krantentaal: voorkomen en parameters.Thesis

- 2013De skoon bysin in Afrikaanse krantentaal: voorkomen en parameters.Thesis

- 2013De skoon bysin in Afrikaanse krantentaal: voorkomen en parameters.Thesis

- 1989Norme vir Afrikaans: enkele riglyne by die gebruik van Afrikaans.Academica

- 2003Norme vir Afrikaans: enkele riglyne by die gebruik van Afrikaans.Van Schaik

- 2003Norme vir Afrikaans: enkele riglyne by die gebruik van Afrikaans.Van Schaik

- 2016Over lexicale voorkeuren in de alternantie tussen de “skoon bysin” en de “dat-bysin”: Een distinctieve collexeemanalyse.Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe56117-133,

- 2016Over lexicale voorkeuren in de alternantie tussen de “skoon bysin” en de “dat-bysin”: Een distinctieve collexeemanalyse.Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe56117-133,

- 2016Over lexicale voorkeuren in de alternantie tussen de “skoon bysin” en de “dat-bysin”: Een distinctieve collexeemanalyse.Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe56117-133,

- 2016Over lexicale voorkeuren in de alternantie tussen de “skoon bysin” en de “dat-bysin”: Een distinctieve collexeemanalyse.Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe56117-133,

- 2004Verb sequence and placement: Afrikaans and Dutch compared.Bundels

- 2010Sentence-initial I think (that) and I believe (that): Prosodic evidence for use as main clause, comment clause and discourse marker.Studies in Language34(1)36-74

- 2012From Khoekhoe foreigner talk via Hottentot Dutch to Afrikaans: the creation of a novel grammar.Bundels

- 1991The influence of English on Afrikaans: a case study of linguistic change in a language contact situation.Academica

- 1991The influence of English on Afrikaans: a case study of linguistic change in a language contact situation.Academica

- 1993A grammar of Afrikaans.ReeksMouton de Gruyter

- 2005Toward a semantic account of that-deletion in EnglishLinguistics43(2)345-382

- 2005Toward a semantic account of that-deletion in EnglishLinguistics43(2)345-382

- 2005Toward a semantic account of that-deletion in EnglishLinguistics43(2)345-382

- 2005Toward a semantic account of that-deletion in EnglishLinguistics43(2)345-382

- 1987Sinsvolgorde in Afrikaans. [Aequence of sentences in Afrikaans.]Thesis

- 1989Plasing in Afrikaanse afhanklike sinne.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde730-37,

- 1989Plasing in Afrikaanse afhanklike sinne.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde730-37,

- 1989Plasing in Afrikaanse afhanklike sinne.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde730-37,

- 1989Plasing in Afrikaanse afhanklike sinne.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde730-37,

- 1989Plasing in Afrikaanse afhanklike sinne.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde730-37,

- 1989Plasing in Afrikaanse afhanklike sinne.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde730-37,

- 1989Plasing in Afrikaanse afhanklike sinne.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde730-37,

- 1989Plasing in Afrikaanse afhanklike sinne.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde730-37,

- 1989Plasing in Afrikaanse afhanklike sinne.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde730-37,

- 1989Plasing in Afrikaanse afhanklike sinne.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde730-37,

- 1989Plasing in Afrikaanse afhanklike sinne.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde730-37,

- 1990Skoon afhanklike sinne in Afrikaanse spreektaal.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde8116-120,

- 1990Skoon afhanklike sinne in Afrikaanse spreektaal.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde8116-120,