- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

This section discusses some general issues related to the clause-initial position, subsection I starts with a review of the operation that moves the finite verb from its clause-final position into the C-position in the left-periphery of the clause; see Chapter 10 for a more extensive discussion. Verb movement results in verb-first (henceforth: V1) structures and Subsection II will demonstrate how verb-second (henceforth: V2) clauses can be derived by subsequent topicalization or question formation, subsection III will show that the clause-initial position can be filled by at most one constituent, subsection IV will show that there are no constraints on the syntactic function of the constituent occupying the clause-initial position; it seems that virtually any clausal constituent can occupy this position. This is related to the fact, discussed in Subsection V, that the clause-initial constituent normally has a specific information-structural function, subject-initial main clauses are exceptional in this respect but Subsection VI will show that there are more reasons to set such cases apart, subsection VII concludes by showing that main and embedded clauses exhibit different behavior with respect to their initial position: for example, while the initial position of declarative main clauses is normally filled by the subject or some topicalized element, the initial position of declarative embedded clauses is normally empty.

- I. Verb movement: Verb-first/second

- II. Topicalization and question formation

- III. The clause-initial position contains at most one constituent

- IV. The syntactic function of the constituent in clause-initial position

- V. Clause-initial constituents are semantically marked

- VI. Subject-initial sentences are special

- VII. Main versus embedded clauses

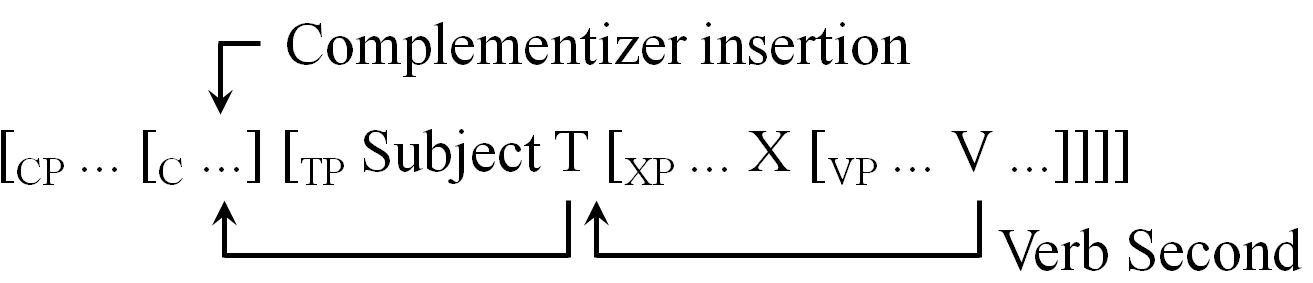

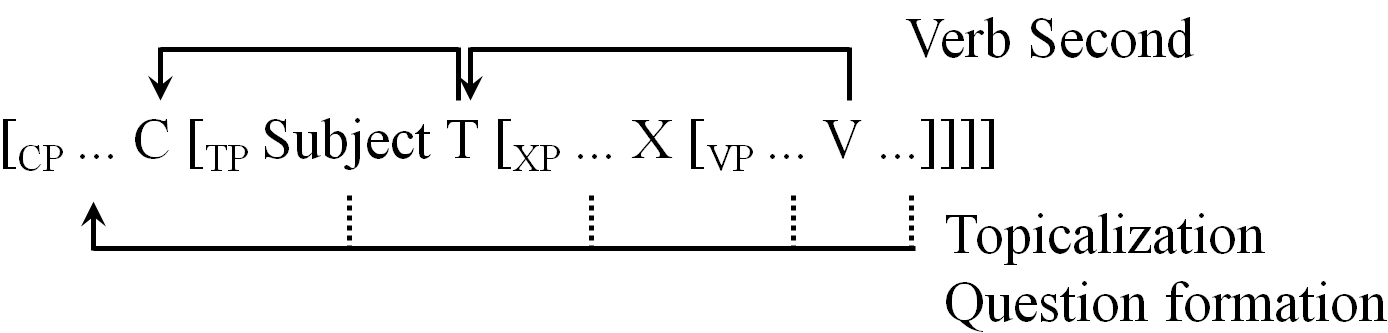

Since Paardekooper (1961) it has normally been assumed that complementizers in embedded clauses and finite verbs in main clauses occupy the same structural position in the clause. In the traditional version of generative grammar this is derived as depicted in (4). In embedded clauses, the complementizer dat'that' or of'if' must be inserted in the C(omplementizer)-position. In main clauses, the finite verb is moved into this position from its original VP-internal position via the intermediate T(ense)-position; note that, for theoretical reasons, it is normally also assumed that the finite verb also moves through all intermediate X-positions, but this is not depicted here. Verb-movement is blocked in embedded clauses because complementizer insertion is obligatory in this context and thus occupies the target position of the finite verb. The obligatoriness of verb-movement in main clauses follows if we assume that the C-position must be filled but that complementizer insertion is restricted to embedded clauses.

|

The claim that complementizers in embedded clauses and finite verbs in main clauses are placed in the C-position is empirically motivated by Paardekooper's observation that they display similar placement with respect to referential subject pronouns like zij'she'. Putting subject-initial main clauses aside for the moment, the examples in (5) show that such pronouns are always right-adjacent to the finite verb in main clauses or right-adjacent to the complementizer in embedded clauses.

| a. | Gisteren | was zij | voor zaken | in Utrecht. | main clause | |

| yesterday | was she | on business | in Utrecht | |||

| 'Yesterday she was in Utrecht on business.' | ||||||

| a'. | * | Gisteren was voor zaken zij in Utrecht. |

| b. | Ik | dacht | [dat | zij | voor zaken | in Utrecht was]. | embedded clause | |

| I | thought | that | she | on business | in Utrecht was | |||

| 'I thought that she was in Utrecht on business.' | ||||||||

| b'. | * | Ik dacht dat voor zaken zij in Utrecht was. |

This observation can be derived immediately if we assume that subject pronouns obligatorily occupy the regular subject position, that is, the specifier position of TP, which is indicated by "Subject" in representation (4).

The derivation of V1 and V2-clauses is now very straightforward and simple. The clause-initial position can be identified with the specifier position of CP, indicated in (4) by the dots preceding the C-position. V1-clauses arise if this position remains empty, while V2-clauses arise if this position is filled by some constituent. Prototypical cases of V1-clauses are yes/no-questions such as (6a); whether the clause-initial position is truly empty or filled by some phonetically empty question operator is difficult to establish; we will postpone this issue to Section 11.2.1. V2-clauses arise if some constituent is moved into the specifier position of CP, that is, the clause-initial position: the movement operation involved is used to derive various different kinds of constructions like the topicalization construction in (6b) and the wh-question in (6c); the traces indicate the original position of the moved phrase.

| a. | Heeft | Jan dat boek | met plezier | gelezen? | V1; yes/no-question | |

| has | Jan that book | with pleasure | read | |||

| 'Has Jan enjoyed reading that book?' | ||||||

| b. | Dat boeki | heeft | Jan ti | met plezier | gelezen. | V2; topicalization | |

| that book | has | Jan | with pleasure | read | |||

| 'That book, Jan has enjoyed reading.' | |||||||

| c. | Welk boeki | heeft | Jan ti | met plezier | gelezen? | V2; wh-question | |

| what book | has | Jan | with pleasure | read | |||

| 'Which book has Jan enjoyed reading?' | |||||||

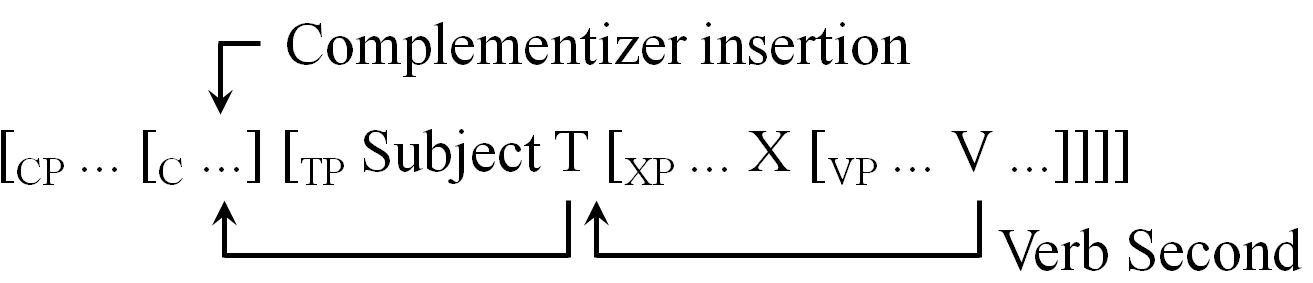

Consider again the representation in (4), repeated below as (7). Functional elements like T and C are generally assumed to contain certain semantic and morphosyntactic features. The functional element T(ense), for example, is normally assumed to contain the feature ±finite; this verbal feature is what enables the movement of the finite verb into T, as depicted in representation (7). A positive value for this feature enables T to assign nominative case to the subject of the clause, and it is assumed that this morphosyntactic relation between T and the subject enables the latter to be moved into the specifier position of T; we refer the reader to Section 9.5 for arguments showing that the subject is base-generated in a VP-internal position.

|

For our present discussion it is important to emphasize that the relation between the T-head and the subject is unique: a finite clause has (at most) one nominative argument. In the active clause in (8a) nominative case is assigned to Peter/hij and in the passive clause in (8b) it is assigned to Marie/zij, but there are no clauses with two nominative nominal arguments: *Hij bezocht zij'*He visited she'.

| a. | Peter/Hij | heeft | gisteren | Marie/haar | bezocht. | |

| Peter/he | has | yesterday | Marie/her | visited | ||

| 'Pete/He visited Marie/her yesterday.' | ||||||

| b. | Marie/zij | werd | gisteren | door Peter/hem | bezocht . | |

| Marie/she | was | yesterday | by Peter/him | visited | ||

| 'Marie/she was visited by Peter/him yesterday.' | ||||||

It is often assumed that the element C has features related to the illocutionary force of the clause: the feature ±q, for example, may determine whether we are dealing with a declarative or an interrogative clause. Contrary to ±finite, the feature ±q has no overt morphological manifestation on the verb in Dutch but it does affect the morphological form of the complementizer: the feature -q requires it to be spelled-out as dat'that' while +q requires it to be spelled-out as of'if'.

| a. | Marie | zegt [CP | dat[-Q] | Peter het boek | met plezier | gelezen | heeft]. | |

| Marie | says | that | Peter the book | with pleasure | read | has | ||

| 'Marie says that Peter has enjoyed reading the book the book.' | ||||||||

| b. | Marie | vraagt [CP | of[+Q] | Peter het boek | met plezier | gelezen | heeft]. | |

| Marie | asks | if | Peter the book | with pleasure | read | has | ||

| 'Marie is asking whether Peter has enjoyed reading the book the book.' | ||||||||

The examples in (10) show that the value of the feature ±q also determines what element may occupy the specifier position of CP in main clauses: while the (a)-examples show that it is possible to topicalize the direct object het boek or the indirect object aan Marie in the declarative clauses, the (b)- and (c)-examples show that topicalization is excluded in interrogative clauses; the feature +q only allows the specifier of CP to be filled by a wh-phrase. Note that (10b'&c') are (marginally) acceptable as echo-questions but this is of course not the reading intended here.

| a. | Dit boeki | heeft | Peter ti | aan Marie | aangeboden. | |

| this book | has | Peter | to Marie | prt.-offered | ||

| 'This book, Peter has offered to Marie.' | ||||||

| a'. | Aan Mariei | heeft | Peter dit boek ti | aangeboden. | |

| to Marie | has | Peter this book | prt.-offered | ||

| 'To Marie, Peter has offered this book.' | |||||

| b. | Welk boeki | heeft | Peter ti | aan Marie | aangeboden? | |

| which book | has | Peter | to Marie | prt.-offered | ||

| 'Which book has Peter offered to Marie?' | ||||||

| b'. | * | Aan Mariei | heeft | Peter | welk boek ti | aangeboden? |

| to Marie | has | Peter | which book | prt.-offered |

| c. | Aan wie | heeft | Peter dit boek ti | aangeboden? | |

| to who | has | Peter this book | prt.-offered | ||

| 'To whom has Peter offered this book?' | |||||

| c'. | * | Dit boek | heeft | Peter ti | aan wie | aangeboden? |

| this book | has | Peter | to who | prt.-offered |

The examples in (11) further show that the specifier position of CP can contain at most one constituent; it is impossible to move more than one constituent into the clause-initial position. First, although the (a)-examples in (10) have shown that the direct and the indirect object can both be topicalized, example (11a) shows that they cannot be topicalized simultaneously. Second, although example (11b) shows that a clause may contain more than one wh-phrase, example (11b') shows that it is not possible to place more than one wh-phrase in its clause-initial position.

| a. | * | Dit boeki | aan Mariej | heeft | Jan ti tj | aangeboden. |

| this book | to Marie | has | Jan | prt.-offered |

| b. | Welk boeki | heeft | Jan ti | aan wie aangeboden? | |

| which book | has | Jan | to who prt.-offered | ||

| 'Which book did Jan offer to whom?' | |||||

| b'. | * | Welk boeki | aan wiej | heeft ti tj | Jan | aangeboden? |

| which book | to who | has | Jan | prt.-offered |

The examples in (10) and (11) show that the specifier position of CP resembles the specifier position of T in that it can be filled by at most one constituent which is compatible with its feature specification: like the specifier of T[+finite] can only be occupied by a nominative argument, the specifier of C[+Q] can only be occupied by a wh-phrase. Note that the C-feature +q postulated in this subsection may be part of a larger set of features, as the constituents in clause-initial position may have a variety of special semantic functions; we return to this in Section 11.3.

The fact illustrated in (11) that the clause-initial position may contain at most one constituent underlies the standard Dutch constituency test: anything that may occur in clause-initial position can be analyzed as a constituent. The utility of this test is based on the fact that virtually all clausal constituents can occupy this position. The examples in (12), for instance, show that topicalization and question formation affect arguments and adverbial phrases alike.

| a. | Jan zal | morgen | dat boek | lezen. | |

| Jan will | tomorrow | that book | read | ||

| 'Jan will read that book tomorrow.' | |||||

| b. | Dat boeki | zal | Jan morgen ti | lezen. | object | |

| that book | will | Jan tomorrow | read | |||

| 'That book, Jan will read tomorrow.' | ||||||

| b'. | Wati | zal | Jan morgen ti | lezen? | |

| what | will | Jan tomorrow | read | ||

| 'What will Jan read tomorrow?' | |||||

| c. | Morgeni | zal | Jan ti | dat boek | lezen. | adverbial phrase | |

| tomorrow | will | Jan | that book | read | |||

| 'Tomorrow Jan will read that book.' | |||||||

| c'. | Wanneeri | zal | Jan ti | dat boek | lezen? | |

| when | will | Jan | that book | read | ||

| 'When will Jan read that book?' | ||||||

The examples in (13) show that complementives can also be placed in clause-initial position. For the sake of brevity, (13) illustrates this for wh-questions only, but similar examples are common in topicalization constructions as well; cf., e.g., Boven mijn bed hang ik jouw schilderij'Over my bed, I will hang your painting.'

| a. | Ik | wil | dierenarts | worden. | Wati | wil | jij ti | worden? | |

| I | want | vet | become | what | want | you | become | ||

| 'I want to be a vet. What do you want to be?' | |||||||||

| b. | Ik vond de film | saai. | Hoei | vond | jij | hem ti? | |

| I found the movie | boring. | how | found | you | him | ||

| 'I thought the movie boring. What did you think of it?' | |||||||

| b'. | Ik | hang | jouw schilderij | boven mijn bed. | Waari | hang | jij | het mijne ti? | |

| I | hang | your painting | above my bed | where | hang | you | the mine | ||

| 'Iʼll hang your painting over my bed. Where will you hang mine?' | |||||||||

It should be noted however, that the clause-initial position is not only accessible to clausal constituents, but may sometimes also contain parts of clausal constituents. This is illustrated in the (a)-examples in (14) for so-called R-extraction: although the primeless example shows that prepositional objects are normally wh-moved as a whole, the primed example shows that they can easily be split if they have the pronominalized form waar+P; see Section P5 for extensive discussion. Example (14b) shows the same for so-called wat voor-phrases; cf. N4.2.2.

| a. | <Naar> | wie | zoek | je <*naar>? | ||

| for | who | look | you | |||

| 'Who are you looking for?' | ||||||

| a'. | Waar | <naar> | zoek | je | <naar>? | |

| where | for | look | you | for | ||

| 'What are you looking for?' | ||||||

| b. | Wat | <voor een boek> | wil | je <voor een boek> | lezen? | |

| what | for a book | want | you | read | ||

| 'What kind of a book do you want to read?' | ||||||

We must therefore be aware not to jump to the conclusion that we are dealing with a clausal constituent if a certain string of words occurs in clause-initial position: all we can conclude is that we are dealing with a constituent, which may be a clausal constituent but which may also be a subpart of clausal constituent.

The previous subsection has shown that there are no syntactic restrictions on the constituent in clause-initial position, that is, the specifier position of CP; in principle any clausal constituent may be placed in this position. In this respect, the specifier position of CP is of an entirely different nature than the specifier of TP, which is a designated position of the subject. The movements involved in filling these specifiers are therefore also of an entirely different nature, which is sometimes expressed by saying that there is a distinction between A- and A'-movement. A(rgument)-movement is restricted to the nominal arguments, that is, subjects and direct/indirect objects. These movements are triggered by morphosyntactic features like ±finite or ±agreement, which play a role in syntactic relations like structural case (nominative, accusative and dative) assignment and subject/object-verb agreement. A'-movements are not restricted to nominal arguments and are not triggered by morphosyntactic but by semantic features. Features that may play a role in topicalization constructions are the features ±topic and ±focus. The feature +topic introduces the clause-initial constituent as the active discourse topic. An example such as (15a) introduces the referent of the direct object as a (new) discourse topic and it is consequently likely that in a follow-up sentence more information will be provided about this referent. The feature ±focus marks the clause-initial constituent as noteworthy in some sense, which is emphasized by the fact that this constituent is normally assigned extra accent (indicated here by small caps). Example (15b), for example, contrasts the referent of the clause-initial constituent with other entities in a contextually given set.

| a. | Peteri | heb | ik | nog | niet ti | gesproken. | Hij | is nog | op vakantie. | |

| Peter | have | I | not | yet | spoken | he | is still | on holiday | ||

| 'As for Peter, I havenʼt spoken to him yet. Heʼs still on holiday.' | ||||||||||

| b. | Peteri | heb | ik | nog | niet ti | gesproken | (maar | de anderen | wel). | |

| Peter | have | I | not | yet | spoken | but | the others | aff | ||

| 'Peter, I havenʼt spoken to yet, but I did speak to the others.' | ||||||||||

The fact that topicalization does not occur in embedded clauses suggests that the features ±topic and ±focus can be found on the C-heads of main clauses only. This does not hold for the feature ±Q that we find on the C-heads of interrogative clauses, as is clear from the fact illustrated in (16) that such clauses can also be embedded.

| a. | Ik | weet | niet [CP | of[+Q] | ik | dit boek | zal | lezen]. | |

| I | know | not | if | I | this book | will | read | ||

| 'I donʼt know if Iʼll read this book.' | |||||||||

| b. | Ik | weet | niet [CP | welk boek | (of[+Q]) | ik ti | zal | lezen]. | |

| I | know | not | which book | if | I | will | read | ||

| 'I donʼt know which book Iʼll read.' | |||||||||

Observe that the interrogative complementizer of'if' is optional in examples such as (16b), which is related to the fact that there is a certain preference for not pronouncing the complementizer if the clause-initial position is filled. This phenomenon is also found in other languages; see, e.g., Chomsky & Lasnik (1977), who account for this by means of the so-called doubly-filled-compfilter, and Pesetsky (1997/1998), who provides an account in terms of optimality theory.

There are also features like ±relative that occur in embedded clauses only. This feature creates relative clauses and can be held responsible for the movement of relative pronouns into clause-initial position. The percentage signs in the examples in (17) express that the complementizer dat[+rel] is normally not pronounced in Standard Dutch but that it was possible in Middle Dutch and is still possible in various present-day Dutch dialects; see, e.g., Pauwels (1958), Dekkers (1999:ch.3) and references cited there.

| a. | de brief [CP | diei | (%dat[+rel]) | ik | gisteren ti | ontvangen | heb]. | |

| the letter | which | that | I | yesterday | received | have | ||

| 'the letter which I received yesterday' | ||||||||

| b. | de plaats [CP | waari | (%dat[+rel]) | ik | ga ti | slapen] | |

| the place | where | that | I | go | sleep | ||

| 'the place where Iʼm going to sleep' | |||||||

The previous subsection has shown that clause-initial constituents normally play a specific information-structural role (wh-phrase, topic, focus, etc.) in the clause. This was confirmed by the results of a recent corpus-study: "Non-subject material in the Vorfeld (= clause-initial position) is characterized by its (relative) importance." (Bouma 2008). The reason for providing this quote is that Bouma also found that this general characterization does not extend to subject-initial clauses: these are special in that they are normally the most unmarked way of asserting a proposition. That subject-initial clauses are unmarked is clear from the fact that they are generally used if the full sentence consists of new information: the word order in example (18a) is the one we typically get as an answer to the question Wat is er gebeurd?'What has happened?'. This raises the question as to whether subject-initial main clauses have the same overall structure as other V2-constructions, as is assumed in the more traditional versions of generative grammar where an example such as (18a) is derived as in (18a).

| a. | Marie | heeft | haar boek | verkocht. | |

| Marie | has | her book | sold | ||

| 'Marie has sold her book.' | |||||

| b. |  |

If the movement into the specifier of CP is indeed motivated by some semantic feature, the fact that (18a) is the unmarked way of expressing the proposition have read(Marie,this book) would be quite surprising. Furthermore, Section 9.3 has shown that there are various other conspicuous differences between clause-initial subjects and other topicalized phrases. The most conspicuous difference is that the former can be a phonetically reduced pronoun, but the latter cannot. Consider the examples in (19). The primeless examples show that the subject can be clause-initial regardless of its form: it can be a full noun phrase like Marie, a full pronoun like zij or a phonetically reduced pronoun like ze. The primed examples show that topicalized objects are different: topicalization is possible if it has the form of a full noun phrase like Peter or a full pronoun like hem, but not if it has the form of the weak (phonetically reduced) pronoun 'm. The reason for this is that while topicalized objects must be accented (which is indicated by means of small caps) clause-initial subjects can remain unstressed.

| a. | Marie helpt | Peter/hem/'m. | |

| Marie helps | Peter/him/him | ||

| 'Marie is helping Peter/him.' | |||

| a'. | Peter | helpt | Marie/zij/ze. | |

| Peter | helps | Marie/she/she | ||

| 'Peter, Marie/she is helping.' | ||||

| b. | Zij | helpt | Peter/hem/'m | |

| she | helps | Peter/him/him. | ||

| 'Sheʼs helping Peter/him.' | ||||

| b'. | Hem | helpt | Marie/zij/ze. | |

| him | helps | Marie/she/she | ||

| 'Him, Marie/she is helping.' | ||||

| c. | Ze | helpt | Peter/hem/'m | |

| she | helps | Peter/him/him. | ||

| 'Sheʼs helping Peter/him.' | ||||

| c'. | * | ʼM | helpt | Marie/zij/ze. |

| him | helps | Marie/she/she |

That topicalized phrases must be accented can also be illustrated by the examples in (20). The (a)-examples show that while the adverbial pro-form daar'there' can readily be topicalized, the phonetically reduced form er cannot. The (b)-examples illustrate the same thing for cases in which these elements function as the nominal part of a pronominal PP.

| a. | Jan heeft | daar/er | gewandeld. | |

| Jan has | there/there | walked | ||

| 'Jan has walked there.' | ||||

| a'. | Daar/*Er | heeft | Jan gewandeld. | |

| there/there | has | Jan walked |

| b. | Jan heeft daar/er mee gespeeld. | |

| Jan has there/there with played | ||

| 'Jan has played with that/it.' |

| b'. | Daar/*Er | heeft | Jan mee | gespeeld. | |

| there/there | has | Jan with | played |

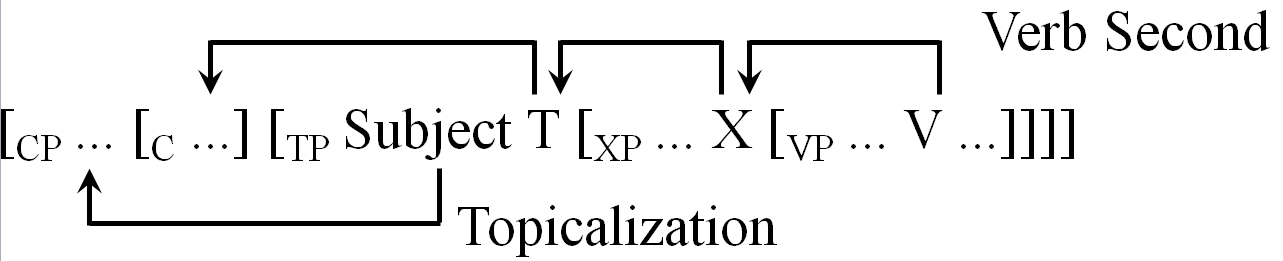

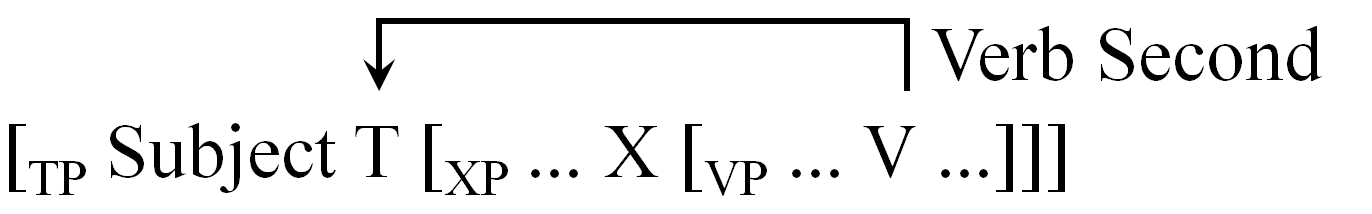

We can readily account for these differences between subject-initial main clauses and other types of V2-clauses if we assume that these have the two different representations in (21): if sentence-initial subjects are not topicalized, there is no reason to expect that such constructions give rise to a marked interpretation or require a special intonation pattern.

| a. | Subject-initial main clause | |

|

| b. | Topicalization and question formation in main clause | |

|

Accepting the two structures in (21) would also make it possible to account for the contrast in verbal inflection in the examples in (22) by making the form of the finite verb sensitive to the position it occupies; if the verb is in T, as in (22a), second person singular agreement is realized by means of a -t ending, but when it is in C, as in (22b&c), it is realized by means of a null morpheme.

| a. | Jij/Je | loop-t | niet | erg snel. | |

| you/you | walk-2sg | not | very fast | ||

| 'You donʼt walk very fast.' | |||||

| b. | Erg snel | loop-Ø | jij/je | niet. | |

| very fast | walk-2sg | you/you | not | ||

| 'You donʼt walk very fast.' | |||||

| c. | Hoe snel loop-Ø | jij/je? | |

| how fast walk-2sg | you/you | ||

| 'How fast do you walk?' | |||

The discussion above thus shows that there are good reasons not to follow the traditional generative view that Dutch main clauses are always CPs; subject-initial main clauses may be special in that they are TPs. This hypothesis may help us to account for the following facts: (i) subject-initial clauses are unmarked assertions, (ii) sentence-initial subjects can be a reduced pronoun and (iii) subject-verb agreement may be sensitive to the position of the subject.

There is a conspicuous difference between the clause-initial positions of main and embedded finite declarative clauses: the examples in (23) show that while the former are normally filled by the subject or some topicalized phrase, the latter are normally empty.

| a. | Jan heeft | Vaslav van Arthur Japin | gelezen. | |

| Jan has | Vaslav by Arthur Japin | read | ||

| 'Jan has read Vaslav by Arthur Japin.' | ||||

| a'. | Vaslav van Arthur Japin | heeft | Jan gelezen. | |

| Vaslav by Arthur Japin | has | Jan read | ||

| 'Vaslav by Arthur Japin Jan has read.' | ||||

| a''. | * | Ø | heeft | Jan | Vaslav van Arthur Japin | gelezen. |

| * | *Ø | has | Jan | Vaslav by Arthur Japin | read |

| b. | Ik | denk [CP Ø | dat [TP | Jan | Vaslav van Arthur Japin | gelezen | heeft]]. | |

| I | think | that | Jan | Vaslav by Arthur Japin | read | has | ||

| 'I think that Jan has read Vaslav by Arthur Japin.' | ||||||||

| b'. | * | Ik | denk [CP | Jani | (dat) [TP ti | Vaslav van Arthur Japin | gelezen | heeft]]. |

| I | think | Jan | that | Vaslav by Arthur Japin | read | has |

| b'' | * | Ik | denk [CP | Vaslav van Arthur Japini | (dat) [TP | Jan ti | gelezen | heeft]]. |

| I | think | Vaslav by Arthur Japin | that | Jan | read | has |

Observe that we placed the complementizers in the primed (b)-examples within parentheses because we have seen that the phonetic content of a complementizer is often omitted if the specifier of CP is filled by phonetic material; see the discussion of the doubly-filled-compfilter in Subsection V.

Such a difference between finite main and dependent clauses does not arise in the case of interrogative clauses. The examples in (24) show that the initial position is phonetically empty in yes/no-questions but filled by some wh-phrase both in main and in embedded clauses.

| a. | Ø | Heeft | Jan | Vaslav van Arthur Japin | gelezen? | |

| Ø | has | Jan | Vaslav by Arthur Japin | read | ||

| 'Has Jan read Vaslav by Arthur Japin?' | ||||||

| a'. | Wati | heeft | Jan ti | gelezen? | |

| what | has | Jan | read | ||

| 'What has Jan read?' | |||||

| b. | Ik | weet niet [CP | Ø of [TP | Jan Vaslav van Arthur Japin | gelezen | heeft]]. | |

| I | know not | Ø if | Jan Vaslav by Arthur Japin | read | has | ||

| 'I donʼt know whether Jan has read Vaslav by Arthur Japin.' | |||||||

| b'. | Ik | weet niet [CP | wati | (of) [TP | Jan ti | gelezen | heeft]]. | |

| I | know not | what | if | Jan | read | has | ||

| 'I donʼt know what Jan has read.' | ||||||||

Finite main and embedded clauses do differ in that only the latter can be used as relative clauses. The examples in (25) show that such clauses require some relative element to be placed in clause-initial position; we already mentioned in Subsection V that the complementizer dat is normally omitted in Standard Dutch relative clauses.

| a. | Dit is de roman [CP | diei | (*dat) [TP | Jan ti | gelezen | heeft]]. | |

| this is the novel | rel | that | Jan | read | has | ||

| 'This is the novel that Jan has read.' | |||||||

| b. | * | Dit is de roman [CP Ø | (dat) [TP | Jan | die | gelezen | heeft]]. |

| this is the novel | that | Jan | rel | read | has |

The initial position of infinitival clauses is normally phonetically empty. Examples such as (26a) are possible but seem to be of an idiomatic nature in colloquial speech; cf. Section 4.2. Note that the complementizer must be empty in these examples, and that PRO stands for the phonetically empty subject of the infinitival clause. For examples such as (26b) it is sometimes assumed that the clause-initial position is filled by a phonetically empty operator OP; we will not discuss such examples here but refer the reader to Section N3.3.3 for more information.

| a. | Ik | weet | niet [CP | wati [C Ø] [TP PRO ti | te doen]]. | |

| I | know | not | what | to do | ||

| 'I donʼt know what to do.' | ||||||

| b. | Dat | is een auto [CP OPi [C | om] [TP PRO ti | te zoenen]]. | |

| that | is a car | comp | to kiss | ||

| 'That is a car to be delighted about/an absolutely delightful car.' | |||||

- 2008Starting a sentence in Dutch. A corpus study of subject- and object-frontingUniverisity of GroningenThesis

- 1977Filters and controlLinguistic Inquiry8425-504

- 1999Derivations & evaluations. On the syntax of subjects and complementizersAmsterdamUniversity of AmsterdamThesis

- 1961Persoonsvorm en voegwoordDe Nieuwe Taalgids54296-301

- 1958Het dialect van Aarschot en omstrekennullnullnullBelgisch Interuniversitair Centrum voor Neerlandistiek

- 1997Optimality theory and syntax: movement and pronunciationArchangeli, Diana & Langendoen, Terence (eds.)Optimality theoryMalden/OxfordBlackwell134-170

- 1998Some optimality principles of sentence pronunciationBarbosa, Pilar, Fox, Danny, Hagstrom, Paul, McGinnis, Martha & Pesetsky, David (eds.)Is the best good enough?Cambridge, MA/LondonMIT Press/MITWPL337-383