- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

The final consonant of the present tense stem of the verbs dwaan /dwa:n/ to do, hawwe /havə/ to have, hoege /huɣə/ need to, sille /sɪlə/ will, shall, sjen /sjɛn/ to see; to look, and wolle /volə/ to want, to wish is often not realized. The consonant-final stem is shown to be the basic form. The consonant-less stem of the highly frequent verb hawwe have appears to have a more independent status.

The verbs dwaan /dwa:n/ to do, hawwe /havə/ to have, hoege /huɣə/ need to, sille /sɪlə/ will, shall, sjen /sjɛn/ to see; to look, and wolle /volə/ to want, to wish have the present tense stems doch /doɣ/, haw /hav/, hoech /huɣ/, sil /sɪl/, sj{o/u}ch /sj{o/ø}ɣ/, and wol /vol/, respectively. With the exception of hoege, these are strong/irregular verbs.

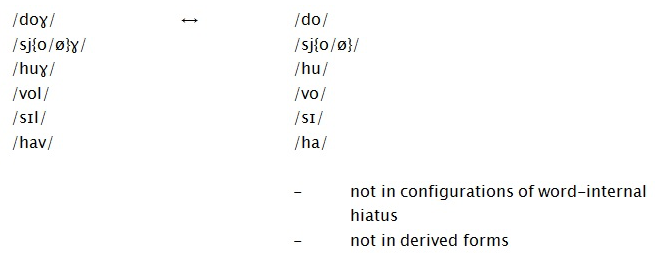

The stem-final consonant is often not realized, which gives rise to the alternating forms in (1) (see also Visser (1988:210-216):

| Verbs with and without final consonant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | With and without final /ɣ/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| doch | /doɣ/ | to do | ~ | do | /do/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| sj{o/u}ch | /sj{o/ø}ɣ/ | to see; to look | ~ | sj{o/u} | /sj{o/ø}/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| hoech | /huɣ/ | to need to | ~ | hoe | /hu/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | With and without final /l/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| wol | /vol/ | to want, to wish | ~ | wo | /vo/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| sil | /sɪl/ | will, shall | ~ | si | /sɪ/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | With and without final /v/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| haw | /hav/ | to have | ~ | ha | /ha/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| hoef | /huv/ | to need to | ~ | hoe | /hu/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

With the exception of ha, the forms in the right-hand column of (1) are not recognized in the official spelling. This also holds for dost and dot (the shortened forms of dochst and docht) in (2) below.

In the remainder of this topic, the stems hoech /huɣ/ and hoef /huv/ will be collapsed into hoech.

In the second and third person singular, both the full and the shortened stem are regularly inflected, as shown for dwaan do in (2):

| The second and third person singular of dwaan 'to do' | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| do dochst | / | do dost | you do | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| hy docht | / | hy dot | he does | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The first person singular present tense of strong/irregular and weak -e-verbs does not carry overt inflection. Since they belong to the class of the so-called preterite present verbs, the third person singular present tense of sille will, shall and wolle to want, to wish is not inflected with /-t/, so it is hy sil he shall, he will and hy wol he wants, he wishes, not *hy silt /sɪl+t/ and *hy wolt /vol+t/. This implies that these shortened stems are free to occur in sentence-final position, which is exemplified in (3):

| The shortened stems in sentence-final position | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik leau, dat ik dat noait wer do | I believe that I that never again do | I believe that I will never do that again | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik tink, dat ik him dêr sj{o/u} | I think that I him there see | I think that I see him there | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik haw sein, dat ik neat hoe | I have said that I nothing want/need | I have said that I do not want/need anything | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik kin dwaan, sa't ik sels wo | I can do as I self want/wish | I can do as I like/please | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik leau, dat ik mar ris op bêd si | I believe that I just a time on bed will | I believe it is about time I go to bed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik leau, dat er ek mei wo | I believe that he also along wants/wishes | I believe that he also wants to come with us | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leausto, dat er dat dwaan si? | believe.2SG that he that do will | Do you really believe that he will do that? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In sentence-final position − as in ik leau, dat ik mar ris op bêd si I think it is about time I went to bed and leausto, dat er dat dwaan si? do you really think that he will do that? − the shortened stem si /sɪ/ sounds somewhat strange and uncommon. In any case, si is (far) less common in that position than the other shortened stems.

The present plural form of strong/irregular verbs ends in schwa. This schwa drops quite easily if the verb is followed by another word in the same sentence, especially when the latter is vowel-initial (see Schwa deletion as a synchronic process: other configurations than hiatus). This conditioning factor is absent if the verb is in sentence-final position. Moreover, schwa is generally not deleted preceding a pause.

The shortened verb stems at hand resist inflection with -e. The only exception is hoeë /hu+ə/, in which case we end up with a bisyllabic surface form, with the glide [w] inserted between stem-final /u/ and schwa (see The resolution of hiatus between a monophthong and a following vowel): [(hu)(wə)]. But doë /do+ə/, sjoë //sjo+ə/ or sjuë /sjø+ə/, woë /vo+ə/, and sië /sɪ+ə/ do not occur. This may be due to the short monophthong they contain, for glide insertion only takes place after a long monophthong. Since glide insertion is impossible, inflection with -e creates a word-internal configuration of two vowels in hiatus, which is not allowed in Frisian (see The resolution of vocalic hiatus). But why then are these inflected stems not realized with a centring diphthong, resulting in the monosyllabic forms doë /do+ə/ [(doə)], sjoë /sjo+ə/ [(sjoə)] or sjuë /sjø+ə/ [sjøə], woë /vo+ə/ [(voə)], and sië /sɪ+ə/ [(sɪə)]? Words ending in /-oə/ and /-øə/ are rare in Frisian, though they do occur, whereas words ending in /-ɪə/ are quite common. The right generalization here seems to be that it is only tautomorphemic vowel sequences which translate into diphthongs in Frisian, as a consequence of which sequences of stem vowel + inflectional vowel do not. Therefore, if the embedded clauses in (3) have a plural subject, only the inflected full stems of the verbs occur, as in (4):

| The impossibility of the shortened stems with a plural subject in sentence-final position | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik leau, dat sokken dat noait wer dogge /*do | I believe that such people that never again do | I believe that such people will never do that again | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik tink, dat wy him dêr sj{o/u}gge/*sj{o/u} | I think that we him there see | I think that we see him there | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik haw sein, dat wy neat hoege/*hoe | I have said that we nothing want/need | I have said that we do not want/need anything | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wy kinne dwaan, sa't wy sels wolle /*wo | we can do as we self want/wish | We can do as we like/please | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik leau dat wy mar ris op bêd sille/*si | I believe that we just a time on bed will | I think it is about time we go to bed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik leau, dat de bern ek mei wolle/*wo | I believe that the children also along want/wish | I believe that the children also want to come with us | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leausto, dat se dat dwaan sille/*si? | believe.2SG that they that do will | Do you really think that they will do that? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the context of inversion the inflectional -e ( [-ə]) of the plural form of verbs drops quite easily. As argued above, the shortened verb stems under discussion resist inflection with -e, so the inversion context should be a kind of ‘natural habitat’ for them. And so it is, as shown in (5), which contains the same sort of sentences as (4), but now with inversion of subject and finite verb:

| The shortened stems with a plural subject in the context of inversion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dat dogge/do sokken noait wer | that do such people never again | They will never do that again | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dêr sj{o/u}gge/sj{o/u} wy him | there see we him | We see him there | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dat hoege/hoe wy net | that want/need we not | We do not want/need that | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dat wolle/wo wy sa hawwe | that want we so have | That is how we want it | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sille/si wy mar net ris op bêd? | shall/will we just not a time on bed | Is not it about time we went to bed? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wolle/wo jim ek mei? | want you (subject form, pl., familiar and polite) also along | Do you also want to come with us? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sille/si jim dat wier dwaan? | shall/will you (subject form, pl., familiar and polite) that truly do | Will you really do that? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The shortened verb forms are so common in this context that the full forms seem to be restricted to a more formal and 'correct' speech style.

Since inflectional -e easily drops in the context of inversion, the full forms without final schwa − dogg' /doɣ/, sj{o/u}gg' /sj{o/ø}ɣ/, hoeg' /huɣ/, woll' /vol/, and sill' /sɪl/− are also expected to occur in the sentences in (5). Realizations like woll'wy [volvi] and sill'jim [sɪljɪm] occur, although they are less frequent than both wolle wy/sille jim and wo wy/si jim. On the other hand, both dogg'se [doɣzə] and sj{o/u}gg'wy [sj{o/ø}ɣvi] are very uncommon, if not unacceptable, realizations. Since woll' and sill' end in the liquid /l/, a segment with a high degree of sonority, there is a much better syllable contact in woll'wy [(vol)(vi)] and sill'jim [(sɪl)(jɪm)] than there is in dogg'se [(doɣ)(zə)] and sj{o/u}gg'wy [(sj{o/ø}ɣ)(vi)], in which the first syllable ends in an obstruent (the voiced velar fricative /ɣ/). This may cause the differences in commonness or acceptability here.

Attaching a vowel-initial suffix to these shortened stems creates a configuration of word-internal vocalic hiatus, which is disallowed in Frisian (see The resolution of vocalic hiatus). On purely phonological grounds therefore these stems cannot figure in such derivations. Examples of derivations on the basis of the full stem are provided in (6):

| Examples of derivations with vowel/initial suffixes based on the full stems | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| drokdoggerich | /drok+doɣ+ərəɣ/ | fussed, fussy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| spoeksjoggerich | /spu:k+sjoɣ+ərəɣ/ | skittish, shy (of a horse) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| steksjoggerich | /stɛk+sjoɣ+ərəɣ/ | short-sighted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| dogger | /doɣ+ər/ | doer, go-getter | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| neidogger | /[[nai#doɣ]+ər]/ | imitator | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| sjogger | /sjoɣ+ər/ | spectator, onlooker | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| neisjogger | /[[nai#sjoɣ]+ər]/ | corrector | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ûnsjoggens | /[[un+sjoɣ]+əns]/ | unsightliness, ugliness | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Consonant-initial derivational suffixes, however, combine with the full stem as well:

| Examples of derivations with consonant-initial suffixes based on the full stems | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ûnsjochber | /[un+[sjoɣ+bər]]/ | invisible | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| dochsel | /doɣ+səl/ | what one can do | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Also when the verb is the right-hand part of the derivation, it is only the full stem which shows up:

| Examples of derivations with the full stems as the right-hand part | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| gedoch | /ɡə+doɣ/ | goings-on, fuss | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| besjoch | /bə+sjoɣ/ | in: | gâns - hawwe | attract a great deal of attention, notice | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (foar)útsjoch | /[[([fwar#])[yt]]#[sjoɣ]]/ | prospect, outlook | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| omsjoch | /om#sjoɣ/ | in: | yn in - | in the wink of an eye | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| steksjoch | /stɛk#sjoɣ/ | short-sighted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ûnsjoch | /un+sjoɣ/ | unsightly, ugly | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The full stem is also in use in the gerund form of the infinitive, which ends in -en ( /-ən/) (see Infinitive):

| The full stems in the gerund form of the infinitive | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it/te hoegen | /huɣ+ən/ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it/te wollen | /vol+ən/ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it/te sillen | /sɪl+ən/ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The gerund of dwaan and sjen is it/te dwaan and it/te sjen, respectively, and not *it/te doggen and *it/te sj{o/u}ggen. Both dwaan and sjen belong to the seven verbs with an infinitive ending in -n, all of which have a gerund form which equals that of the infinitive.

All in all, there is a good deal of evidence that the full form of these verb stems is the basic form, from which the shortened form is an allomorph.

The verb hawwe /havə/ stands out. For many speakers, the full stem haw /hav/ has been replaced by the shortened stem ha /ha/. Firstly, as noted before, the finite forms of both the second and the third person singular present tense no longer show any variation between forms with and without [f] (< stem-final /v/). It is do hast [hast] you have and hy hat [hat] he has, respectively, whereas *do hafst [hafst] and *hy haft [haft] are out. Secondly, ha can occur in sentence-final position, whether it is in agreement with a singular or a plural subject:

| Examples of ha in sentence-final position | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik tink dat ik wol in kopy ha | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik tink dat wy wol in kopy ha | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Thirdly, ha can also be used as an infinitive, both the verbal infinitive and the gerund. This is a most outstanding feature of ha: as a verbal infinitive, it is the only one ending in a full vowel, and as a gerund, it is the only one which does not end in -en. This behaviour is exemplified below:

| Ha as an infinitive | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dat moatte wy net ha | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It ha fan in eigen hûs is djoer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hy hoecht gjin grut kado te ha | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This, however, is not the whole story. Though do hast [hast] you have and hy hat [hat] he has do not have the variants *do hafst [hafst] and *hy haft [haft], the form ha in (10) and (11) does have variant realizations with /v/:

| Variant realizations with /v/ of ha | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik tink dat ik wol in kopy haw | [haf] | I think that I all right a copy have | I think that I do have a copy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik tink dat wy wol in kopy hawwe | I think that we all right a copy have | [havə] | I think that we do have a copy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dat moatte wy net hawwe | [havə] | that must we not have | we would not want that to happen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It hawwen | [havən] | fan in eigen hûs is djoer | the having of an own house is expensive | having a house of one's own is expensive | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hy hoecht gjin grut kado te hawwen | [havən] | he needs no huge present to have | We need not give him a huge present | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also the derivations in (13):

| Derivations based on the full stem /hav/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| gelykhawwerich | /ɡəlik+hav+ərəɣ/ | insistent on being right (all the time) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| leafhawwer | /[[lɪəv#hav]+ər]/ | lover | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The impossibility of the shortened stem in the above forms can be explained on phonological grounds: the central vowel /a/ is not able to trigger the insertion of a glide (see The resolution of hiatus between /a(:)/ and a following vowel), as a result of which a forbidden configuration of word-internal vocalic hiatus would arise. So, although haw /hav/ and ha /ha/ act as two separate and independent stems, the former has a wider distribution than the latter.

Basically, the verb have has four dialectal variants: hawwe [havə], hewwe [hɛvə], habbe [habə], and hebbe [hɛbə], of which hawwe is the (written) Standard Frisian form. This variation has been left out of consideration here.

In some dialects, the stem haw /hav/ has been replaced by har /har/, which has developed intervocalically; see Veenstra (1994) on how this new stem may have developed.

As noted before, the above verbs all belong to the strong/irregular class, with the exception of hoege need to, which is a fully regular, weak verb. The verb hoege has the full stem hoech /huɣ/ and the shortened one hoe /hu/. Since weak verbs do not have a separate past tense stem and past participle, the shortened stem hoe can also be the basis for the past tense and the past participle. So, we needed to can be either wy hoegden /huɣ+dən/ or wy hoeden /hu+dən/, whereas the past participle can be both hoegd /huɣ+t/ [huxt] and hoed /hu+d/ [hut], as in dat hie net hoegd/hoed you didn't have to do that; you should not have done that. As a monosyllabic weak past participle ending in /d/, hoed can be expanded with the ending -en of the strong past participle: dat hie net hoeden /hu+d+ən/ [hudn̩] you did not have to do that; you should not have done that.

A word-internal configuration of two vowels in hiatus is not allowed in Frisian. This is different for such a configuration between two separate words. This means that the shortened stems may occur in sentences like the following:

| Examples of the shortened stems in sentence-internal configurations of hiatus | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik si Albert | [sɪ ʔɔlbət] | wol freegje | I will Albert all right ask | I will ask Albert | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik wo Elske | [vo ʔɛlskə] | wol freegje | I want Elske all right ask | I will ask Elske | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik do altyd | [do ʔɔltit] | myn bêst | I do always my best | I always do my best | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ik sjo/sju alle | [sjo ʔɔlə / sjø ʔɔlə] | dagen nei it sjoernaal fan 8 oere | I see all days to the newscast of eight hour | I watch the 8 o'clock news every day | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As indicated, hiatus may be resolved here by the insertion of the glottal stop.

As shown in (2), both the full and the shortened stem of the verbs at hand can be inflected. However, sille will, shall and wolle want, wish are deviant in this respect. The second person singular present tense forms do silst you will, you shall and do wolst you want, you wish are never realized with [l], but only as [sɪst] and [vost]. There is no general process of /l/-deletion in verbs with a stem ending in /-ɪl/ or /-ol/, for dolle /dolə/ to dig and tille /tɪlə/ to lift, to raise; to carry, for example, have the inflected forms do dolst you dig and do tilst you lift, you raise; you carry, which can only be realized with [l], as [dolst]/ [*dost] and [tɪlst]/ [*tɪst].

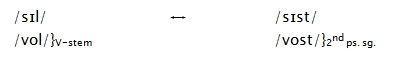

We might express the relation between the full stem of sille/wolle and the second person singular present tense form as follows:

This specific statement is complemented by the more general statement concerning the relation between the verb stems with and without final consonant below:- 1994Merkwaardige vormen van de werkwoorden hebben, doen, slaan en zien in het FriesTaal en tongval46110-136

- 1988In pear klitisearringsferskynsels yn it FryskDyk, dr. S. & Haan, dr. G.J. (eds.)Wurdfoarried en Wurdgrammatika. In bondel leksikale stúdzjesLjouwertFryske Akademy, Ljouwert175-222