- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

This section briefly discusses the so-called middle field of the clause, that is, that part of the clause bounded to the right by the verb(s) in clause-final position (if present), and to the left by the complementizer in an embedded clause or the finite verb in a main clause. The middle field of the examples in (66) is in italics.

| a. | Gisteren | heeft | Jan | met plezier | dat boek | gelezen. | |

| yesterday | has | Jan | with pleasure | that book | read | ||

| 'Jan enjoyed reading that book yesterday.' | |||||||

| b. | Ik | denk | [dat | Jan | met plezier | dat boek | gelezen | heeft]. | |

| I | think | that | Jan | with pleasure | that book | read | has | ||

| 'I think that Jan enjoyed reading that book.' | |||||||||

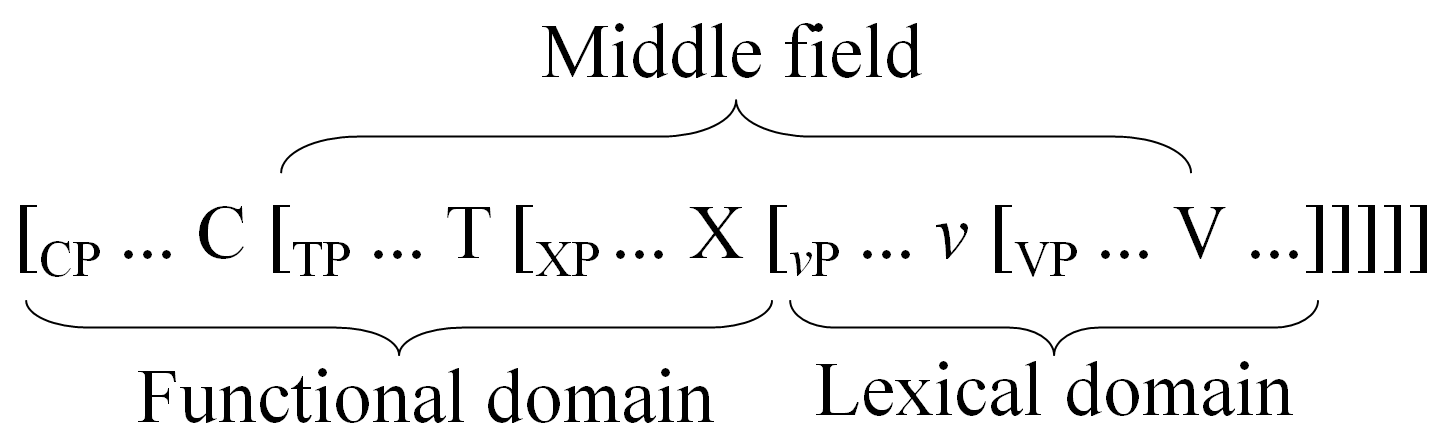

The middle field of a clause is not a constituent and not even a phrase, but refers to a set of positions within the clause. If we adopt the representation in (59b) and assume that C is the position of the complementizer or the finite verb in second position and that the clause-final verb occupies V, the middle field is as indicated in (67).

|

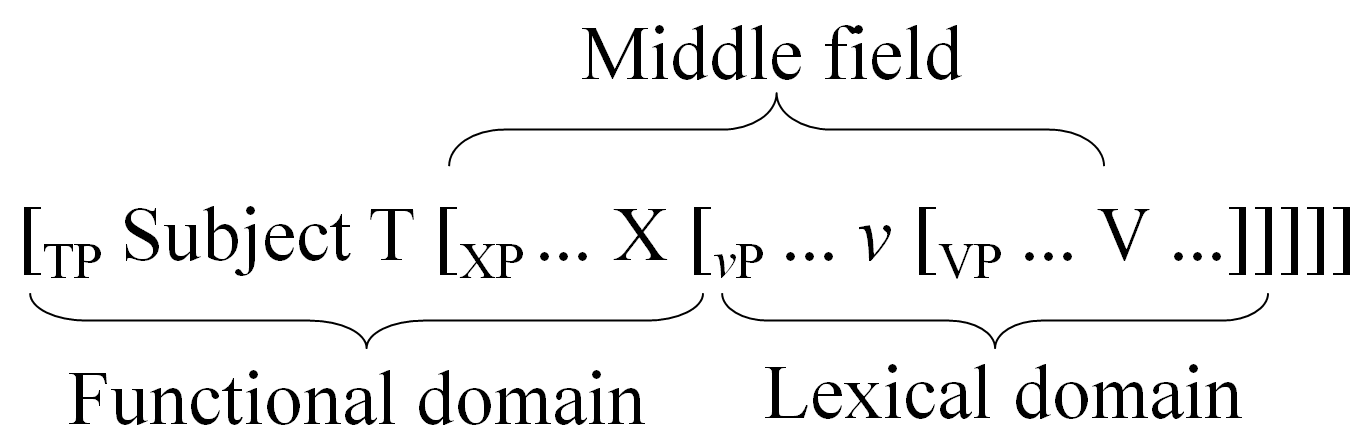

The fact that the middle field does not refer to a discrete entity in the clausal domain makes it clear immediately that we are dealing with a pre-theoretical notion. This is also evident from the fact that it refers to a slightly smaller domain in subject-initial sentences, such as Jan heeft met plezier dat boek gelezen, if such sentences are not CPs but TPs, as suggested by the data discussed in Section 9.3, sub IV.

| a. | Jan heeft | met plezier | dat boek | gelezen. | |

| Jan has | with pleasure | that book | read |

| b. |  |

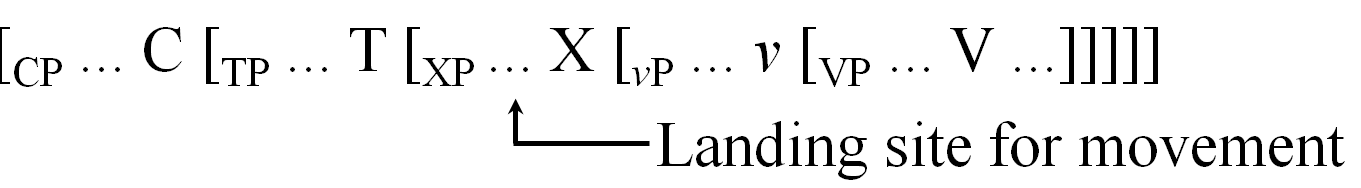

Recall that X in the structures in (67) and (68) stands for an indeterminate number of functional heads that may be needed to provide a full description of the structure of the clause. More specifically, just as the specifier of C may function as the landing site of wh-movement and topicalization, the lower functional heads may likewise introduce specifiers that can function as landing sites for several other types of movement.

|

Whether the postulation of such functional heads is indeed necessary or whether there are alternative ways of expressing the same theoretical intuition is a controversial matter, but it is evident that Dutch exhibits considerable freedom in word order (relative to many other languages) in the middle field of the clause. Example (70a), for instance, shows that a direct object can be left-adjacent to the verb(s) in clause-final position, but may also occur farther to the left. Similarly, example (70b) shows that the subject may be right-adjacent to the complementizer or finite verb in second position, but can also occur farther to the right.

| a. | dat | Jan | <het boek> | waarschijnlijk <het boek> | koopt. | |

| that | Jan | the book | probably | buys | ||

| 'that Jan will probably buy the book.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | <die jongen> | waarschijnlijk <die jongen> | het boek koopt. | |

| that | that boy | probably | the book buys | ||

| 'that that boy will probably buy the book.' | |||||

The following subsections discuss a number of cases of word order variation in the middle field of the clause in terms of leftward movement without being too specific about the functional heads that may be involved (if any). We will show, however, that these movements may have semantic effects and/or may be related to certain semantic features of the moved elements. Before beginning with this, we want to make some remarks about a number of elements typically occurring at the right-hand edge of the middle field of the clause.

Predicative complements (complementives) normally precede the clause-final verb(s), whatever their category, as shown in (73) for nominal, adjectival and prepositional complementives. This word order restriction is especially conspicuous in the case of predicative PPs like op het bed in (71c) given that PP-complements normally can readily appear in postverbal position; cf. Section 9.4.

| a. | dat | ik | hem | <een schat> | vind <*een schat>. | nominal | |

| that | I | him | a dear | consider | |||

| 'that I believe him to be a darling.' | |||||||

| b. | dat | Peter Marie <erg kwaad> | maakt <*erg kwaad>. | adjectival | |

| that | Peter Marie very angry | makes | |||

| 'that Peter makes Marie very angry.' | |||||

| c. | dat | Jan zijn kleren | <op het bed> | gooit <*op het bed>. | prepositional | |

| that | Jan his clothes | on the bed | throws | |||

| 'that Jan throws his clothes on the bed.' | ||||||

Complementives can easily be moved into clause-initial position by topicalization or wh -movement, but in the middle field they normally occupy the position adjacent to the verb(s) in clause-final position, as illustrated in the examples in (72). We will see in Subsection IIID, however, that they may sometimes be moved to the left if they receive contrastive accent.

| a. | dat | ik | hem | <*een schat> | nog steeds | <een schat> vind. | nominal | |

| that | I | him | a dear | yet still | consider | |||

| 'that I still believe him to be a darling.' | ||||||||

| b. | dat | Peter Marie | <*erg kwaad> | vaak <erg kwaad> | maakt. | adjectival | |

| that | Peter Marie | very angry | often | makes | |||

| 'that Peter often makes Marie very angry.' | |||||||

| c. | dat | Jan zijn kleren | <*op het bed> | meestal <op het bed> | gooit. | prepositional | |

| that | Jan his clothes | on the bed | normally | throws | |||

| 'that Jan normally throws his clothes on the bed.' | |||||||

The tendency of complementives to immediately precede the verb(s) in clause-final position makes it possible to use complementives as a diagnostic for extraposition. This is illustrated in (73) where we see that nominal arguments (here the subject of the complementives themselves) must precede the complementives, whereas clausal arguments must follow them, just as in the case of clause-final verbs.

| a. | Jan maakte | <het probleem> | duidelijk <*het probleem>. | |

| Jan made | the problem | clear | ||

| 'Jan clarified the problem.' | ||||

| b. | Jan maakte | <*dat het onmogelijk was> | duidelijk <dat het onmogelijk was>. | |

| Jan made | that it impossible was | clear | ||

| 'Jan made it clear that it was impossible.' | ||||

Verbal particles are perhaps even more reliable indicators of extraposition. Like the complementives in the examples above, they are normally left-adjacent to the verb(s) in clause-final position, but unlike complementives they cannot be moved leftwards because it is normally not easy to assign them contrastive accent. The examples in (74) with the particle verb afleiden 'to deduce from' show that, in neutral sentences, the PP-complement may either precede or follow the particle, and that the particle follows nominal but precedes clausal complements. Again, this is precisely what we find with clause-final verbs; cf, Subsection I.

| a. | Els leidde | deze conclusie | <uit zijn weigering> | af <uit zijn weigering>. | |

| Els deduced | this conclusion | from his refusal | prt. | ||

| 'Els concluded this from his refusal.' | |||||

| b. | Els leidde | <uit zijn weigering> | af <uit zijn weigering> | dat hij bang was. | |

| Els deduced | from his refusal | prt. | that he scared was | ||

| 'Els deduced from his refusal that he was scared.' | |||||

The examples in (73) and (74) show that in clauses without clause-final verbs complementives and verbal particles can be used as reliable indicators of the right boundary of the middle field.

Dutch allows a wide variety of word orders in the middle field of the clause. This subsection discusses the relative order of nominal arguments and clausal adverbs like waarschijnlijk'probably'. All nominal arguments of the verb may either precede or follow such adverbs, which is illustrated in (75) by means of a subject and a direct object. The word order variation in (75) is not entirely free but restricted by information-structural considerations, more specifically, the division between presupposition (discourse-old information) and focus (discourse-new information); cf. Verhagen (1986).

| a. | dat | waarschijnlijk | Marie | dat boek | wil | kopen. | |

| that | probably | Marie | that book | wants | buy | ||

| 'that Marie probably wants to buy that book.' | |||||||

| a'. | dat | Marie waarschijnlijk | dat boek | wil | kopen. | |

| that | Marie probably | that book | wants | buy | ||

| 'that Marie probably wants to buy that book.' | ||||||

| b. | Marie | heeft | waarschijnlijk | dat boek | gekocht. | |

| Marie | has | probably | that book | bought | ||

| 'Marie has probably bought that book.' | ||||||

| b'. | Marie | heeft | dat boek | waarschijnlijk | gekocht. | |

| Marie | has | that book | probably | bought | ||

| 'Marie has probably bought that book.' | ||||||

The distinction between presupposition and focus is especially clear in question-answer contexts, as we will illustrate below for the cases of object movement in the (b)-examples. A question like (76a) introduces the referent of dat boek as a topic of discussion, and therefore the answer preferably has the noun phrase in front of the adverb, that is, presents the noun phrase as discourse-old information; in actual speech, this is made even clearer by replacing the noun phrase dat boek by the personal pronoun het, which typically refers to discourse-old information.

| a. | Wat | heeft | Marie | met | dat boek | gedaan? | question | |

| what | has | Marie | with | that book | done |

| b. | ?? | Zij | heeft | waarschijnlijk | dat boek | gekocht. | answer = (75b) |

| she | has | probably | that book | bought |

| b'. | Zij | heeft | dat boek | waarschijnlijk | gekocht. | answer = (75b') | |

| she | has | that book | probably | bought |

A question like (77a), on the other hand, clearly does not presuppose the referent of the noun phrase dat boek to be a topic of discourse, and now the preferred answer has the noun phrase after the adverb. The answer in (77b') with the nominal object preceding the adverb is only possible if the context provides more information, e.g., if the participants in the discourse know that Marie had the choice between buying a specific book or a specific CD; in that case the nominal object preceding the adverb is likely to have contrastive accent.

| a. | Wat | heeft | Marie gekocht? | question | |

| what | has | Jan read |

| b. | Zij | heeft | waarschijnlijk | dat boek | gekocht. | answer = (75b) | |

| she | has | probably | that book | bought |

| b'. | *? | Zij | heeft | dat boek | waarschijnlijk | gekocht. | answer = (75b') |

| she | has | that book | probably | bought |

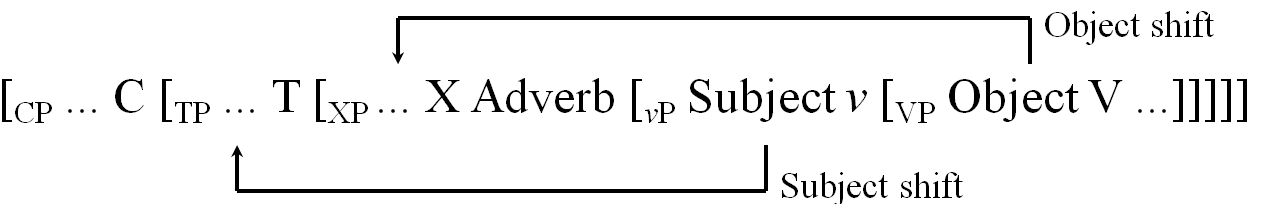

There are various analyses available for the word order variations in (75); see the reviews in the introduction in Corver & Van Riemsdijk (1994) and Broekhuis (2007/2008: Section 2.1). It has been claimed, for example, that the orders in (75) are simply base-generated, and that the word order variation should be accounted for by assuming either variable base-positions for the nominal arguments, as in Neeleman (1994a/1994b), or variable base-positions for the adverbial phrase, as in Vanden Wyngaerd (1989). Here we opt for a movement analysis, according to which the nominal argument is generated to the right of the clausal adverb and optionally shifts into a more leftward position as indicated in (78).

|

The optional subject shift in (78) is probably due to the same movement that we find in passive constructions such as (79b). As this movement places the subject in the position where nominative case is assigned, it has been suggested that the landing site of the optional object shift in (78) is a designated position in which accusative case is assigned; see Broekhuis (2008:ch.3) and the references cited there.

| a. | Gisteren | heeft | JanSubject | MarieIO | de boekenDO | aangeboden. | |

| yesterday | has | Jan | Marie | the books | prt.-offered | ||

| 'Yesterday Jan offered Marie the books.' | |||||||

| b. | Gisteren | werden | <de boeken> | MarieIO <de boeken> | aangeboden. | |

| yesterday | were | the books | Marie | prt.-offered | ||

| 'Yesterday the books were offered to Marie (by Jan).' | ||||||

The claim that subject and object shift target the nominative and accusative case positions implies that we are dealing with so-called A-movement. This is supported by the fact discussed in Subsection IIIA that this movement is restricted to nominal arguments; Section 13.2 will argue that nominal argument shift has more hallmarks of A-movement.

Subsection II has shown that nominal arguments can occupy different positions in relation to the adverbial phrases in the clause; this was illustrated by means of the placement of subjects and direct objects vis-à-vis clausal adverbs like waarschijnlijk'probably'. We suggested that the word order variation is due to optional movement of the subject/object into a designated case position in the functional domain of the clause. If this suggestion is on the right track, we predict that this type of movement is restricted to nominal arguments: PP-complements of the verb, for example, are not assigned case and are therefore not associated either with a designated position in which case could be assigned. This raises the question as to how such PPs are able to occupy different positions in the middle field of the clause, subsection A will show that the movement involved differs in non-trivial ways from nominal argument shift. The subsequent subsections will show that there are various other types of movements that affect the word order in the middle field of the clause: negation-, focus-, and topic movement. As their names suggest, these movements are clearly related to certain semantic properties of the moved elements.

That PP-complements may occupy different surface positions in the clause is illustrated in the examples in (80), taken from Neeleman (1994a).

| a. | dat | Jan nauwelijks | op mijn opmerking | reageerde. | |

| that | Jan hardly | on my remark | reacted | ||

| 'that Jan hardly reacted to my remark.' | |||||

| b. | dat | Jan op mijn opmerking | nauwelijks | reageerde. | |

| that | Jan on my remark | hardly | reacted |

That the difference in placement is the result of movement receives support from the fact illustrated in (81) that R-extraction from the PP is only possible if the stranded preposition follows the clausal adverb (in this case nauwelijks'hardly'); if the (b)-examples in (80) and (81) are derived from the (a)-examples by leftward movement of the PP, this may be accounted for by appealing to the freezing effect. Note that we added the time adverb toen'then' in (81) in order to make the split of the pronominal PP daarop visible.

| a. | dat | Jan daar | toen | nauwelijks | op | reageerde. | |

| that | Jan there | then | hardly | on | reacted | ||

| 'that Jan hardly reacted to that then.' | |||||||

| b. | * | dat | Jan daar | toen | op | nauwelijks | reageerde. |

| that | Jan there | then | on | hardly | reacted |

An important reason for assuming that the movement which derives the order in (80b) is different from nominal argument shift has to do with the distribution of PPs that contain a definite pronoun, subsection II has already mentioned that definite subject/object pronouns normally undergo nominal argument shift: example (82a) is acceptable only if the pronoun hem is assigned contrastive accent: Jan nodigt waarschijnlijk hem uit (niet haar)'Jan will probably invite him (not her)'.

| a. | * | Jan nodigt waarschijnlijk | hem/ʼm | uit. |

| Jan invites probably | him/him | prt |

| b. | Jan nodigt | hem/ʼm | waarschijnlijk | uit. | |

| Jan invites | him/him | probably | prt. | ||

| 'Jan will probably invite him.' | |||||

The examples in (83) show that this does not hold for PP-complements: if the nominal part of the PP is a definite pronoun, leftward movement is optional while it is excluded if the pronoun is phonetically reduced. It should be clear that the division between discourse-old and discourse-new information has no bearing on the leftward movement of PP-complements.

| a. | dat | Jan nauwelijks | naar hem/ʼm | luisterde. | |

| that | Jan hardly | to him/him | listened | ||

| 'that Jan hardly listened to him/him.' | |||||

| a'. | dat Jan naar hem/*ʼm nauwelijks luisterde. |

| b. | dat | Jan nauwelijks | naar haar/ʼr | keek. | |

| that | Jan hardly | at her/her | looked | ||

| 'that Jan hardly looked at her/her.' | |||||

| b'. | dat Jan naar haar/*ʼr nauwelijks keek. |

The unacceptability of the reduced pronouns in the primed examples is especially remarkable in light of the fact that nominal argument shift typically has the effect of destressing the moved element. Some speakers report that they accept examples such as (80b) only if the nominal complement of the PP is contrastively stressed: if true, this would suggest that we are dealing with focus movement, which will be the topic of Subsection C. That the moved PPs must be stressed is supported by the fact that the pronouns in the primed examples of (83) differ from the shifted pronoun in (82b) in that they cannot be phonetically reduced.

A second reason for assuming that the movement in (80b) is different from nominal argument shift is related to this effect: leftward movement of a complement PP under a neutral, that is, non-contrastive intonation pattern is only possible with a restricted set of adverbial phrases. If we replace the negative adverbial phrase nauwelijks'hardly' in (80b) by the adverbial phrase gisteren'yesterday', leftward movement of the PP gives rise to a degraded result (which can only be improved by giving the PP emphatic or contrastive stress). This is illustrated in (84) with three different PP-complements.

| a. | Jan heeft | nauwelijks/gisteren | op mijn opmerkingen | gereageerd. | |

| Jan has | hardly/yesterday | on my remarks | reacted |

| a'. | Jan heeft op mijn opmerkingen nauwelijks/*gisteren gereageerd. |

| b. | Jan heeft | nauwelijks/gisteren | naar Marie | gekeken. | |

| Jan has | hardly/yesterday | at Marie | looked |

| b'. | Jan heeft naar Marie nauwelijks/*gisteren gekeken. |

| c. | Jan heeft | gisteren | op vader | gewacht. | |

| Jan has | yesterday | for father | waited |

| c'. | * | Jan heeft op vader gisteren gewacht. |

The primed examples in (84) with the adverb gisteren contrast sharply with similar examples with object shift, which can easily cross adverbs like gisteren: Ik heb <dat boek> gisteren <dat boek> gelezen'I read that book yesterday'. For completeness' sake, note that some speakers report that the acceptability of the primed examples in (84) improves when gisteren is given emphatic accent.

Finally, the (a)-examples in (85) show that leftward movement of a PP-complement across an adverbial PP is always blocked, whereas object shift across such an adverbial PP is easily possible. For completeness' sake, note that the unacceptability of leftward movement in (85a) cannot be accounted for by assuming some constraint that prohibits movement of a complement of a certain categorial type across an adverbial phrase of the same categorial type, given that such a constraint would incorrectly exclude object shift across the adverbially used noun phrase deze middag'this afternoon' in example (85b); cf. Verhagen (1986:78).

| a. | dat | Jan <*op Marie> | na de vergadering <op Marie> | wachtte. | |

| that | Jan for Marie | after the meeting | waited | ||

| 'that Jan waited for Marie after the meeting.' | |||||

| a'. | dat | Jan <het boek> | na de vergadering <het boek> | wegbracht. | |

| that | Jan the book | after the meeting | away-brought | ||

| 'that Jan delivered the book after the meeting.' | |||||

| b. | dat | Jan <dat boek> | deze middag <dat boek> | zal wegbrengen. | |

| that | Jan that book | this afternoon | will away-bring | ||

| 'that Jan will deliver that book this afternoon.' | |||||

The discussion above has shown (contra Neeleman 1994a and Haeberli 2002) that leftward movement of PP-complements exhibits a behavior deviating from nominal argument shift, which in its turn suggests that it is a movement of some different type. The following subsections will show that there are indeed other types of leftward movement that may affect the word order in the middle field of the clause.

Haegeman (1995) has argued for West-Flemish that negative phrases expressing sentential negation undergo obligatory leftward movement into the specifier of a functional head Neg; she further claims that this functional head can optionally be expressed morphologically by the negative clitic en: da Valère niemand (en-)kent'that Valère does not know anyone'. Although Standard Dutch does not have this negative clitic, it is possible to show that it does have the postulated leftward movement of negative phrases; cf. Klooster (1994). At first sight, the claim that Standard Dutch has negation movement may be surprising, given that negative direct objects as well as PP-complements with a negative nominal part are normally left-adjacent to the verb(s) in clause-final position.

| a. | Jan heeft | <*niets> | waarschijnlijk <niets> | gezien. | |

| Jan has | nothing | probably | seen | ||

| 'Jan has probably not seen anything.' | |||||

| b. | Jan zal | <*op niemand> | waarschijnlijk <op niemand> | wachten. | |

| Jan will | for nobody | probably | waited | ||

| 'Jan will probably not wait for anyone.' | |||||

That Standard Dutch has obligatory negation movement becomes evident, however, when we consider somewhat more complex examples. First, consider the examples in (87) with the adjectival complementive tevreden'content/pleased', which takes a PP-complement headed by the preposition over'about'. Although example (87a) shows that the PP-complement can either precede or follow the adjective, example (87b) strongly suggests that the A-PP order is the base order: leftward movement of the PP across the adjectival head gives rise to a freezing effect.

| a. | Jan is <over Peter> | erg tevreden <over Peter>. | |

| Jan is with Peter | very content | ||

| 'Jan is very content with Peter.' | |||

| b. | de jongen | waar | Jan <*over> | erg tevreden <over> | is | |

| the boy | where | Jan with | very content | is | ||

| 'the boy whom Jan is very content with' | ||||||

Example (88) shows that the PP-complement obligatorily moves to the left if its nominal part expresses sentence negation; examples with the order in (88a) are only acceptable with constituent negation: Jan is tevreden met niets'Jan is content with anything' does not mean that Jan is not pleased with anything but, on the contrary, that he is even content with very little (cf. Haegeman 1995:130-1).

| a. | * | Jan is erg tevreden | over niemand. |

| Jan is very content | about no.one |

| b. | Jan is over niemand | erg tevreden. | |

| Jan is about no.one | very content | ||

| 'Jan is not quite content about anyone.' | |||

The reason why negation movement is normally not visible in Standard Dutch is that the landing site of this movement is a relatively low position in the middle field of the clause and often applies string-vacuously as a result. This will be clear from the fact illustrated in (89a) that the negative phrase from (88) preferably follows the clausal adverb waarschijnlijk'probably' under neutral intonation (the unacceptable order improves somewhat if the negative noun phrase is assigned contrastive accent). We have added example (89b) to show that it is not a coincidence that the PP-complement of the adjective is moved to this position following waarschijnlijk: the negative adverb niet'not' appears to be base-generated in this position.

| a. | Jan is <*over niemand> | waarschijnlijk <over niemand> | erg tevreden. | |

| Jan is about no.one | probably | very content | ||

| 'Jan is probably not quite content about anyone.' | ||||

| b. | Jan is <*niet> | waarschijnlijk <niet> | erg tevreden. | |

| Jan is not | probably | very content | ||

| 'Jan is probably not quite content.' | ||||

That we are dealing with an obligatory leftward movement is also supported by the examples in (90); example (90a) shows again that PP-complements can normally either precede or follow the clause-final verb; if the nominal part of the PP-complement expresses sentence negation, however, the PP-complement must precede the verb, which would follow immediately if it undergoes obligatory leftward movement.

| a. | Jan wil | <op zijn vader> | wachten <op zijn vader>. | |

| Jan wants | for his father | wait | ||

| 'Jan wants to wait for his father.' | ||||

| b. | Jan wil | <op niemand> | wachten <*op niemand>. | |

| Jan wants | for nobody | wait | ||

| 'Jan does not want to wait for anyone.' | ||||

This subsection has shown that phrases expressing sentence negation obligatorily move into some designated position to the right of the modal adverb waarschijnlijk'probably'. This shows that there are movement operations affecting the order of the constituents in the middle field of the clause that are different from nominal argument shift, given that the latter movement typically crosses the modal adverb.

The notion of focus used here pertains to certain elements in the clause that are phonetically highlighted by means of accent, that is, emphatic and contrastive focus. Emphatic focus highlights one of the constituents in the clause, as in (91a). Contrastive focus is normally used to express that a certain predicate exclusively applies to a certain entity or to deny a certain presupposition on the part of the hearer, as in (91b).

| a. | Ik | heb | hem | een boek | gegeven. | |

| I | have | him | a book | given | ||

| 'I have given him a book.' | ||||||

| b. | Nee, | ik | heb | hem | een boek | gegeven | (en geen plaat). | |

| no, | I | have | him | a book | given | and not a record | ||

| 'No, I gave him a book (and not a record).' | ||||||||

Although example (92a) strongly suggests that focused phrases may remain in their base-position, example (92b) shows that they can also occur in clause-initial position.

| a. | dat | Jan erg trots | op zijn boek | is | (maar niet op zijn artikel). | |

| that | Jan very proud | of his book | is | but not of his article | ||

| 'that Jan is very proud of his book (but not of his article)' | ||||||

| b. | Op zijn boek | is Jan erg trots | (maar niet op zijn artikel). | |

| of his book | is Jan very proud | but not of his article |

That focus phrases may occur in clause-initial position is not surprising given that cross-linguistically they behave very much like wh -phrases. In the Gbe languages (Kwa, for example), both types of phrases must occupy the clause-initial position and are obligatorily marked with the focus particle wὲ , as shown in the examples in (93) taken from Aboh (2004:ch.7). The same is shown by Hungarian, where interrogative and focused phrases are placed in the same position left-adjacent to the finite verb; see É. Kiss (2002:ch.4) for examples.

| a. | wémà | wὲ | Sέnà | xìá. | |

| book | focus | Sena | readperfective | ||

| 'Sena read a book.' | |||||

| b. | étε | wὲ | Sέnà | xìá? | |

| what | focus | Sena | readperfective | ||

| 'What did Sena read?' | |||||

Given that focus phrases occupy a fixed position in languages like Kwa and Hungarian, it may be somewhat puzzling that in Standard Dutch focus phrases may occupy various positions in the middle field of the clause. The examples in (94) illustrate this by means of the PP-complement of the adjective trots'proud' in (92).

| a. | dat Jan waarschijnlijk | op zijn boek | erg trots | is | (maar niet op zijn artikel). | |

| that Jan probably | of his book | very proud | is | but not on his article | ||

| 'that Jan is probably very proud of his book (but not of his article).' | ||||||

| b. | dat Jan | op zijn boek | waarschijnlijk | erg trots | is | (maar niet op zijn artikel). | |

| that Jan | of his book | probably | very proud | is | but not on his article | ||

| 'that Jan is probably very proud of his book (but not of his article).' | |||||||

That focused phrases may occupy a variety of surface positions in the clause has challenged the standard assumption that there is a unique position for such phrases to move into and has led to proposals adopting a more flexible approach; cf., e.g., Neeleman & Van de Koot 2008. We will not take a stand on this issue here, but simply conclude that the examples in this subsection show that focused phrases can optionally undergo leftward movement.

The term topic is taken quite broadly here as aboutness-topic; it refers to the entity that the sentence is about. Typical examples are given in (95), which show that aboutness-topics are typically accented and may precede the subject if it is focused (which we have forced in (95) by combining the subject with the focus particle alleen'only').

| a. | dat dit boek | alleen Jan | gelezen | heeft. | |

| that this book | only Jan | read | has | ||

| 'that this book only Jan has read.' | |||||

| b. | dat zulke boeken | alleen Jan | wil | lezen. | |

| that such books | only Jan | wants | read | ||

| 'that such books only Jan wants to read.' | |||||

The fact that leftward movement of aboutness-topics may change the underlying order of the arguments in the middle field (a property that according to some also holds for focus movement) shows that we are once more dealing with a movement type that differs from nominal argument shift discussed in Subsection II. That this is the case is also clear from the fact illustrated in (96) that aboutness-topics need not be nominal in nature, but can also be PPs or (complementive) APs.

| a. | dat op die beslissing | alleen Jan | wil | wachten. | |

| that for that decision | only Jan | wants | wait | ||

| 'that only Jan wants to wait for that decision.' | |||||

| b. | dat | zo stom | alleen Jan | kan | zijn. | |

| that | that stupid | only Jan | can | be | ||

| 'that only Jan can be that stupid.' | ||||||

This section has shown that in Standard Dutch the word order in the middle field of the clause is relatively free. Although in older versions of generative grammar this was accounted for by assuming a generic stylistic scrambling rule, the discussion has shown that the attested word order variation is derived by means of a wider set of movement types. The first type is referred to as nominal argument shift: nominal arguments can move out of the lexical domain of the clause into a number of designated positions in the middle field where they are assigned case, provided that they express discourse-old information. There are a number of additional conditions on this type of movement that were ignored here, but the reader can find a discussion of these in Section 13.2. Besides nominal argument shift, there are a number of movement types typically targeting constituents with a specific semantic property: constituents which express sentence negation, which are contrastively focused, or which function as the aboutness-topic of the clause. We have seen that these movements all have their own peculiarities in terms of their landing site: negative phrases obligatorily target a position to the right of modal clausal adverbs like waarschijnlijk'probably'; focus movement is optional and is relatively free when it comes to the choice of its landing site; and aboutness-topics are special in that they can readily precede the subject of the clause if the latter is contrastively focused.

- 2004The morphosyntax of complement-head sequences. Clause structure and word order patterns in KwaOxford University Press

- 2007Subject shift and object shiftJournal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics10109-141

- 2008Derivations and evaluations: object shift in the Germanic languagesnullStudies in Generative GrammarBerlin/New YorkMouton de Gruyter

- 2008Derivations and evaluations: object shift in the Germanic languagesnullStudies in Generative GrammarBerlin/New YorkMouton de Gruyter

- 1994Studies on scrambling: movement and non-movement approaches to free word-order phenomenanullStudies in generative grammar 41Berlin/New YorkMouton de Gruyter

- 2002Features, categories and the syntax of A-positionsnullStudies in Natural Language & Linguistic TheoryDordrecht/Boston/LondonKluwer

- 1995The syntax of negationnullCambridge studies in linguistics 75CambridgeCambridge University Press

- 1995The syntax of negationnullCambridge studies in linguistics 75CambridgeCambridge University Press

- 2002The syntax of HungariannullCambridge syntax GuidesnullCambridge University Press

- 1994Syntactic differentiation in the licensing of polarity itemsHIL Manuscripts243-56

- 1994Scrambling as a D-structure phenomenonCorver, Norbert & Riemsdijk, Henk van (eds.)Studies on scrambling. Movement and non-movement approaches to free word-order phenomenaBerlin/New YorkMouton de Gruyter387-429

- 1994Complex predicatesUtrechtUniversity of UtrechtThesis

- 1994Scrambling as a D-structure phenomenonCorver, Norbert & Riemsdijk, Henk van (eds.)Studies on scrambling. Movement and non-movement approaches to free word-order phenomenaBerlin/New YorkMouton de Gruyter387-429

- 1994Scrambling as a D-structure phenomenonCorver, Norbert & Riemsdijk, Henk van (eds.)Studies on scrambling. Movement and non-movement approaches to free word-order phenomenaBerlin/New YorkMouton de Gruyter387-429

- 2008Dutch scrambling and the nature of discourse templatesThe Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics11137-189

- 1986Linguistic theory and the function of word order in Dutch. A study on interpretive aspects of the order of adverbials and noun phrasesnullnullDordrechtForis Publications

- 1986Linguistic theory and the function of word order in Dutch. A study on interpretive aspects of the order of adverbials and noun phrasesnullnullDordrechtForis Publications

- 1989Object shift as an A-movement ruleMIT Working Papers in Linguistics11256-271