- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

It is to be expected that locational PPs that refer to the null vector cannot be modified by modifiers of orientation or distance; the magnitude of the null vector is zero, and, as a result, it does not have an orientation either. As is illustrated in (34) by means of the preposition binnen, this expectation is normally borne out.

| a. | * | Het huis | staat | recht/schuin | binnen de stadsmuur. |

| the house | stands | straight/diagonally | within the city walls |

| b. | * | Het huis | staat | twee kilometer | binnen de stadsmuur. |

| the house | stands | two kilometer | within the city wall |

Subsection I will show, however, that there are a number of potential counterexamples to the claim that PPs referring to the null vector cannot be modified by modifiers of orientation and distance, subsection II discusses some other types of modification of these PPs.

This subsection discusses several examples that at first sight seem to involve modification for orientation or distance. We will show, however, that these examples do not involve true counterexamples to the claim that PPs referring to the null vector cannot be modified by modifiers of orientation or distance.

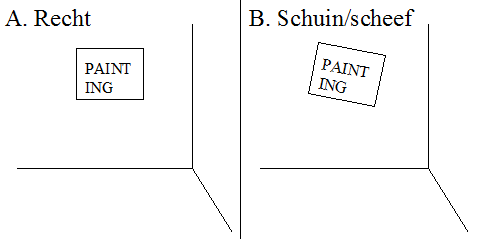

Example (35a) is fully acceptable, but the meaning of recht/schuin seems to differ from the intended modification meaning (viz. orientation); recht/schuin do not modify the position of the located object het schilderij with respect to the reference object de muur, but seem to refer to the way the painting is hanging on the wall, as in Figure 5. In other words, the adjectives recht/schuin are predicated of the noun phrase het schilderij'the painting' and must therefore be analyzed as supplementives, just like the adjectives in (35b). That recht and schuin do not act as a modifier of the PP is supported by the fact that they can also appear if the locational PP is dropped.

| a. | Het schilderij | hangt | recht/schuin | (aan de muur). | |

| the painting | hangs | straight/diagonal | on the wall |

| b. | Het schilderij | hangt | netjes/scheef/slordig | (aan de muur). | |

| the painting | hangs | properly/diagonal/untidy | on the wall |

Rechts'right' and links'left' in (36a) also seem to lack the intended modification meaning: these prepositions just indicate the place of attachment of the flashing blue light, and do not modify the orientation of the (null) vector denoted by the preposition op'on'. In this respect, they resemble elements like midden'middle' and voor/achter'in front of/behind' in (36b).

| a. | Het zwaailicht | zit | rechts/links | op de auto. | |

| the blue light | sits | right/left | on the car | ||

| 'The flashing blue light is attached to the left/right side of the car.' | |||||

| b. | Het zwaailicht | zit | midden/voor/achter | op de auto. | |

| the blue light | sits | middle/in.front.of/behind | on the car | ||

| 'The flashing blue light is attached to the center/front/back of the car.' | |||||

Other elements that can be used in a way similar to links/rechts, midden and achter/voor in (36) are boven/onder'above/under' which are in a paradigm with midden. Some examples are given in (37).

| a. | Jan zit | midden | op de ladder. | |

| Jan sits | middle | on the stepladder. | ||

| 'Jan is sitting in the middle of the stepladder.' | ||||

| b. | Jan zit | boven/onder | op de ladder. | |

| Jan sits | above/under | on the stepladder | ||

| 'Jan is sitting on top/ at the bottom of the stepladder.' | ||||

The examples in (36) and (37) do, of course, involve some kind of modification of the locational PP op de ladder, which expresses the core meaning of the clause Jan zit op de ladder'Jan is sitting on the stepladder'. This is clearest in the cases of midden and onder, since the relevant examples in (37) become ungrammatical if the PP is dropped, as is shown in (38a). In the other cases, this is less clear because the resulting structures are acceptable; the meaning of the clauses, however, changes considerably. This is illustrated in (38b) for boven in (37b), which now receives the meaning “upstairs”.

| a. | * | Jan zit | midden/onder. |

| Jan sits | middle/under |

| b. | Jan zit boven. | |

| 'Jan is sitting upstairs.' |

Note in passing that, in accordance with this, example (37b) with boven is actually ambiguous: it can be translated not only as “Jan is sitting on top of the stepladder” but also as “Jan is sitting upstairs on the stepladder”. In the latter case, it does not act as the antonym of onder, but as the antonym of beneden'downstairs'; see Section 3.5 for discussion.

The question we want to address now is whether the examples in (36) and (37) involve adverbial modification of the locational PP or modification of some other sort. Although it is difficult to give a definite answer to this question, the following subsections will show that there are several reasons for assuming that we are not dealing with adverbial modification, but with compounding.

The examples in (30), repeated here as (39), have shown that it is not the preposition itself that is modified by an adverbial phrase but the full PP. This is clear from the fact that in case of R-pronominalization, the R-word er can intervene between the modifier and the preposition.

| a. | Dicht/Vlak | bij het huis | stond | een boom. | |

| close | near the house | stood | a tree | ||

| 'A tree stood close to the house.' | |||||

| b. | [Dicht/Vlak [PP | er | bij]] | stond | een boom. | |

| close | there | near | stood | a tree |

If we consider examples involving the elements links/rechts, midden, achter/voor and boven/onder, however, it turns out that the R-pronoun cannot intervene between most of these elements and the PP. This is shown in the primed examples in (40).

| a. | Links/Rechts | op de auto | zit | een zwaailicht. | |

| left/right | on the car | sits | a blue.light |

| a'. | * | Link/Rechts er op zit een zwaailicht. |

| b. | Voor/Achter/Midden | in de kerk | staat | een groot orgel. | |

| in.front.of/behind/middle | in the church | stands | a big organ | ||

| 'A big organ stands in the front/back/middle of the church.' | |||||

| b'. | * | Voor/Achter/Midden er in staat een groot orgel. |

| c. | Boven/Onder | op het blikje | staat | de productiedatum. | |

| above/under | on the can | stands | the manufacturing.date | ||

| 'The manufacturing date can be found on top/the bottom of the can.' | |||||

| c'. | * | Boven/Onder er op staat de productiedatum. |

It is not entirely clear how conclusive the primed examples in (40a&b) are, given that (41a&b) show that the order in which the R-pronoun precedes the “modifier” is also bad/marked. In (41c), however, this order gives rise to a fully acceptable result.

| a. | * | Er | links/recht | op zit | een zwaailicht. |

| there | left/right | on sits | a blue.light |

| b. | ? | Er | voor/achter/midden | in | staat | een groot orgel. |

| there | front.of/behind/middle | in | stands | a big organ |

| c. | Er | boven/onder | op | staat | de productiedatum. | |

| there | above/under | on | stands | the manufacturing.date |

The acceptability of (41c) thus shows that the cause of the unacceptability of the primed examples in (40) is not that R-pronominalization itself is impossible, and suggests that the sequence of the modifier and the preposition is impenetrable, which would be consistent with a compound analysis; cf. 1.2.1, sub II.

There are cases in which the complex forms can be used as intransitive adpositions, whereas the simple forms cannot. If achter acts as a modifier of the preposition op in (42a), the ungrammaticality of (42a') with an intransitive adposition would, of course, be highly surprising. In (42b), we give similar examples with bovenin.

| a. | Jan zit | achterop | (de fiets). | |

| Jan sits | on.the.back.of | the bike | ||

| 'Jan is sitting on the back of the bike.' | ||||

| a'. | Jan zit op *(de fiets). |

| b. | Het geld | ligt | bovenin | (de kast). | |

| the money | lies | in.the.upper.part.of | the closet |

| b'. | Het geld ligt in *(de kast). |

If we are dealing with compounds, on the other hand, the difference in acceptability between the primeless and primed examples could simply be accounted for by claiming that the syntactic valence of the simple and complex prepositions differ.

Section 3.1.6 has shown that modified intransitive adpositions cannot permeate the clause-final verb cluster. The complex forms under discussion, on the other hand, can, as is shown in (43). This again favors a compound analysis of the complex forms.

| a. | dat | Marie de hele tijd | voorop | heeft | gelopen. | |

| that | Marie the whole time | in.front | has | walked | ||

| 'that Marie walked in front all the time.' | ||||||

| b. | dat Marie de hele tijd heeft voorop gelopen. |

The discussion in the previous subsections suggests that elements like links/rechts, midden, voor/achter and boven/onder in (36) and (37) are not adverbial modifiers but the first members of a compound. Table 5 gives the possible combinations of these elements with prepositions that denote the null vector. The fact that there are so many question marks in this table indicates that more research is needed.

| preposition | links/rechts | midden | achter/voor | boven/onder |

| in'in/into' | + | + | + | + |

| uit'out/out of' | ? | ? | + | + |

| door'through' | — | ? | — | — |

| aan'on' | ? | ? | + | + |

| op'on' | + | + | + | + |

| over'over' | ? | ? | — | — |

| tegen'against' | + | + | — | — |

| binnen'inside' | — | — | — | — |

Note that a “—” mark does not necessarily imply that the pertinent sequence cannot be found, but that the modification relation is not present. The examples in (44) are acceptable, but they do not involve modification of the PP by the elements achter/voor. This will be clear from the paraphrases; note also that in these cases voor and achter can be topicalized in isolation, which shows that they are independent constituents, comparable to the more common element boven with the meaning “upstairs”; cf. Section 3.5.

| a. | De ladder | stond | achter | tegen de muur. | |

| the ladder | stood | back | against the wall | ||

| 'At the back of the house, the ladder stood against the wall.' | |||||

| a'. | Achter stond de ladder tegen de muur. |

| b. | Jan liep | voor | door de deur. | |

| Jan walked | front | through the door | ||

| 'Jan walked through the front door.' | ||||

| b'. | Voor liep Jan door de deur. |

So far we have not encountered any clear cases of adverbial modification of locational PPs headed by a preposition denoting the null vector, so perhaps we should conclude that such modification is not possible. There are, however, several cases that may involve modification, which we will investigate in the following subsections.

The elements precies'exactly' and bijna'nearly' seem common as modifiers of PPs headed by the prepositions in'in' and op'on'. Some examples are given in (45). We are not dealing with modifiers of orientation or distance in these examples, but with modification of the location of the located object: the use of precies emphasizes that the located object has actually reached the reference object, whereas bijna implies that this nearly was the case.

| a. | Hij | schoot | de pijl | precies/bijna | in | de roos. | |

| he | shot | the arrow | exactly/nearly | into | the bullʼs-eye |

| b. | Zij | gooide | de bal | precies/bijna | op Peters neus. | |

| she | threw | the ball | exactly/nearly | on Peterʼs nose |

That precies acts as a modifier of the PP is clear from the fact illustrated in the (a)-examples in (46) that the phrase precies in de roos must be topicalized as a whole. It is not so clear, however, whether bijna acts as a modifier of the PP: the (b)-examples show that topicalization of the phrase bijna in de roos gives rise to a degraded result, the option of moving bijna in isolation being much preferred.

| a. | Precies in de roos schoot hij de pijl. |

| a'. | * | Precies schoot hij de pijl in de roos. |

| b. | ?? | Bijna in de roos schoot hij de pijl. |

| b'. | Bijna schoot hij de pijl in de roos. |

Although this suggests that bijna does not act as a modifier of the PP but of the clause, drawing such a conclusion may be premature since topicalization of bijna sometimes results in a change of meaning. This is perhaps not so clear in the case of the (b)-examples in (46), but the shift of meaning can be made more conspicuous by means of the examples in (47).

| a. | Jan viel | bijna | in het water. | |

| Jan fell | nearly | into the water |

| b. | Bijna | viel | Jan in het water. | |

| nearly | fell | Jan into the water |

Example (47a) has two readings. The first reading involves modification of the event; it expresses that Jan was about to fall into the water, but succeeded in avoiding it. The second reading involves modification of the location: it is claimed that Jan actually fell, and that he ended up in a position close to the water as a result. Now, when we consider the topicalization construction in (47b), it turns out that only the first reading survives. This suggests that on its second reading, bijna does not act a modifier of the clause but of the PP. If this is indeed the case, the infelicitousness of topicalization constructions such as (46b) remains mysterious.

As the examples in (48) show, PPs headed by in and uit appear to constitute counterexamples to the claim that PPs referring to the null vector cannot be modified by modifiers of distance and orientation. At first sight, the adjectival and nominal phrases in the primeless examples seem to act as modifiers of distance, and the adjectives in the primed examples as modifiers of orientation. We will show in the following subsections, however, that it is not so clear whether we are really dealing with modifiers of the PP.

| a. | De spijker | zit | diep/drie cm | in de muur. | |

| the nail | sits | deep/three cm | in the wall |

| a'. | De spijker | zit | schuin | in de muur. | |

| the nail | sits | diagonally | in the wall |

| b. | De spijker | steekt | drie cm | uit | de muur. | |

| the nail | sticks | three cm | out.of | the wall |

| b'. | De spijker | steekt | schuin | uit | de muur. | |

| the nail | sticks | diagonally | out.of | the wall |

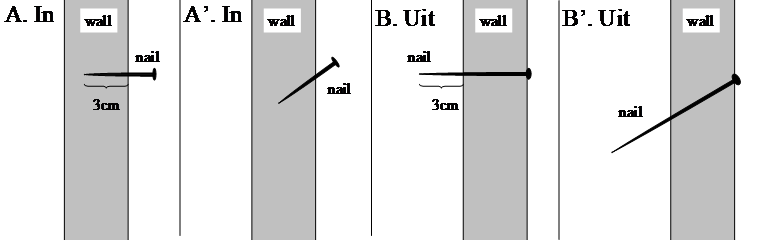

The meaning expressed by the presumed modifiers in (48) is of a completely different nature than in the case of PPs denoting a set of vectors. This is clearest in the case of the alleged modifiers of distance. With PPs denoting a set of vectors, these modifiers indicate what the distance between the reference object and the located object is. In the case of in/uit, on the other hand, the modifier indicates to what extent the located object penetrates/protrudes from the wall; cf. Figure 6A&B. Similarly, schuin in the primed examples indicates in what way the nail penetrates or protrudes from the wall (cf. Figure 6A'&B').

It has been suggested that PPs headed by in and uit do involve vectors, but that they are different from the vectors discussed earlier in that they are not necessarily outward oriented with respect to the reference object, but can also be inward oriented. Note, however, that the nominal measure phrases in (48a&b) are in a paradigm with gedeeltelijk'partly', helemaal'entirely', and voor de helft'half' (lit: for the half), which seem to modify or to be predicated of the located object rather than modifying the PP, so that it is not a priori clear whether we are really dealing with PP modification.

| a. | De spijker | zit | gedeeltelijk/helemaal/voor de helft | in de muur. | |

| the nail | sits | partly/entirely/half | in the wall |

| b. | De spijker | steekt | gedeeltelijk/helemaal/voor de helft | uit de muur. | |

| the nail | sticks | partly/entirely/half | out.of the wall |

The elements discussed above can be used not only in the locational constructions in (48), but also in constructions involving a change of location, as in (50). Observe further that uit differs from in in that it (marginally) takes the adjectival ver'far' as a modifier of distance, not diep'deep'.

| a. | Jan sloeg | de spijker | drie cm/diep/helemaal | in de muur. | |

| Jan hit | the nail | three cm/deep/entirely | into the wall |

| b. | Jan trok | de spijker | drie cm/?ver/helemaal | uit de muur. | |

| Jan pulled | the nail | three cm/far/entirely | out.of the wall |

The ungrammaticality of the examples in (51) shows that these modifiers can only occur with PPs denoting the null vector if some physical contact between the reference and located object is implied. This is consistent with the suggestion above that the modifiers in question actually do not modify a(n inwardly oriented) vector but the located object itself; if there is no physical contact, the located object cannot penetrate/protrude from the reference object, and hence modification is excluded. If so, the notion of “inwardly oriented vector” can be dismissed, and we should conclude that modification of adpositional phrases denoting the null vector is not possible; example (51b) is given a number sign given that it (marginally) allows a reading in which schuin/recht refer to Janʼs posture.

| a. | * | Jan stond | 3 meter/diep/ver | binnen de muur. |

| Jan stood | 3 meters/deep/far | within the wall |

| b. | # | Jan stond | schuin/recht | binnen de muur. |

| Jan stood | diagonally/straight | within the wall |

Still, it should be noted that examples such as (52), in which the distance from the outer boundary of the reference object is measured, are acceptable. Perhaps this is due to the fact that these examples do not involve three-dimensional space. If the budget is one million Euros, example (52a) expresses that the estimate is less. If the time limit is two hours, (52b) expresses that it took the athlete less time to finish. And if the broadcasting station has a range of 100 km, (52c) expresses that Jan lives less than 100 km from it; so it is actually the distance between Janʼs house and the broadcasting station that is relevant in this example.

| a. | De begroting | bleef | ruim/net | binnen de grenzen | van het budget. | |

| the estimate | remained | amply/just | within the boundaries | of the budget |

| b. | De atleet | kwam | ruim/net | binnen de gestelde tijd | binnen. | |

| the athlete | came | amply/just | within the settled time | inside | ||

| 'The athlete remained amply/just within the time limit.' | ||||||

| c. | Jan woont | ruim/net | binnen | het bereik | van de zender. | |

| Jan lives | amply/just | within | the range | of the broadcasting station |

A second reason to doubt that the examples in (48) involve modification of the PPs is that topicalization of the alleged modified PPs gives rise to a marked result. This is clearest with examples involving the preposition uit in the (b)-examples in (48): the examples in (53) seem unacceptable. This is suspect since in cases in which we are unambiguously dealing with modification, topicalization of the full modified PP is easily possible: Een meter boven de deur hangt een schilderij'A painting is hanging one meter above the door'.

| a. | * | Drie cm | uit de muur | steekt | de spijker. |

| three cm | out.of the wall | sticks | the nail |

| b. | * | Schuin | uit de muur | steekt | de spijker. |

| diagonally | out.of the wall | sticks | the nail |

Leftward movement of the noun/adjective phrase in isolation gives rise to significantly better results: topicalization, as in the primeless examples in (54), is perhaps still somewhat marked but wh-movement, as in the primed examples, is perfectly acceptable. Unfortunately, however, this does not tell us much, since we have seen that extracting nominal and adjectival modifiers from the PP is possible as well.

| a. | ? | Drie cm | steekt | de spijker | uit de muur. |

| three cm | sticks | the nail | out.of the wall |

| a'. | Hoeveel cm | steekt | de spijker | uit de muur? | |

| how.many cm | sticks | the nail | out.of the wall |

| b. | ?? | Schuin | steekt | de spijker | uit de muur. |

| diagonally | sticks | the nail | out.of the wall |

| b'. | ? | Hoe | steekt | de spijker | uit de muur? |

| how | sticks | the nail | out.of the wall |

Example (55a) seems somewhat better than (53a). The interpretation of this example differs, however, from that of example (48a); it can no longer express the situation in Figure 6A, but suggests that the nail has completely entered the wall and is now situated on a distance of three centimeters from the surface of the wall. The other examples in (55) do not, however, receive such a divergent interpretation and the judgments are more or less similar to those in (53) and (54).

| a. | ?? | Drie cm | in de muur | zit | de spijker. |

| three cm | in the wall | sits | the nail |

| a'. | ? | Drie cm | zit | de spijker | in de muur. |

| three cm | sits | the nail | in the wall |

| a''. | Hoeveel cm | zit | de spijker | in de muur? | |

| how.many cm | sits | the nail | in the wall |

| b. | * | Schuin | in de muur | zit | de spijker. |

| diagonally | in the wall | sits | the nail |

| b'. | ? | Schuin | zit | de spijker | in de muur. |

| diagonally | sits | the nail | in the wall |

| b''. | Hoe | zit | de spijker | in de muur? | |

| how | sits | the nail | in the wall |

The topicalization data discussed in this subsection at least suggest that example (48) does not involve modification of the PP. We will return to this issue when we discuss modification of directional adpositional phrases; cf. the discussion in Section 3.1.4, sub III.

The previous subsections have shown that the modification possibilities of PPs referring to the null vector are very limited, possibly restricted to modifiers of the type precies'exactly' and bijna'nearly' discussed in Subsection A. In all likelihood, nominal measure phrases like drie cm'three cm' and the adjectives rechts/schuin'straight/diagonally' in the examples discussed in Subsection B do not function as modifiers of the PP.