- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

This section discusses topicalization, the phenomenon that in main clauses virtually any clausal constituent (and sometimes also parts thereof) may precede the finite verb in second position, subsection I starts by showing that, as in the case of question formation, the moved constituent can have a wide range of syntactic functions and can be of any category, subsection II continues by comparing topicalization to question formation (as well as relativization) in order to motivate the claim that it is derived by wh -movement; we will see that, apart from the fact that topicalization is a root phenomenon, there are indeed compelling reasons to assume wh -movement to be involved in the derivation, subsection III repeats some arguments from Section 9.3 for rejecting the traditional view that subject-initial sentences are necessarily derived by topicalization; exclusion of such sentences from the set of topicalization constructions will lead to the conclusion that such constructions have two characteristic properties: they exhibit subject-verb inversion and have a non-neutral reading, subsection IV explores the latter issue, and will show that topicalized phrases often play a special role in discourse; they express a contrastive focus, act as a topic, or perform a special function in the organization of the discourse. Given this, we may expect for contrastively focused phrases and topics at least that wh -movement may pied-pipe a larger phrase if syntactic restrictions prohibits extraction and subsection V shows that this expectation is indeed borne out, subsection VI continues with a discussion of topicalization of clauses and smaller verbal projections: such cases are special because wh -movement of such constituents is not possible in the case of question formation and relativization, subsection VII concludes with a comparison of topicalization in Dutch and English, and will show that there are a number of conspicuous differences, which raises the question as to whether the two should be considered phenomena of the same kind.

- I. Syntactic function and categorial status of the topicalized element

- II. Topicalization is a subcase of wh-movement

- III. Subject-initial clauses versus topicalization constructions

- IV. Information structure: focus and topic

- V. Pied piping and stranding

- VI. Topicalization of verbal projections

- VII. Some differences between English and Dutch topicalization

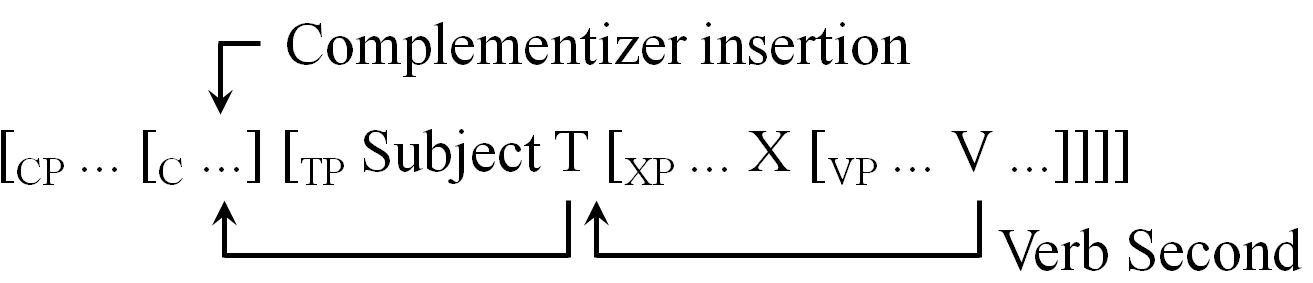

The traditional generative analysis holds that main clauses are derived by placing the finite verb in the second position of the clauses, the so-called C-position in (285), followed by topicalization of some constituent into the so-called clause-initial position, the specifier of CP; see Section 11.1 for details.

|

There seem to be virtually no restrictions on the syntactic function or the categorial status of the topicalized element. The examples in (286) start by showing this for nominal arguments: subjects, direct and indirect objects are all possible in sentence-initial position.

| a. | Marie/Ze | heeft | haar broer/hem | die baan | aangeboden. | subject | |

| Marie/she | has | her brother/him | that job | prt.-offered | |||

| 'Marie/She has offered her brother/him that job.' | |||||||

| b. | Die baan | heeft | ze | her brother/him | aangeboden. | direct object | |

| that job | has | she | her brother/him | prt.-offered | |||

| 'That job, she has offered [to] her brother/him.' | |||||||

| c. | Haar broer/Hem | heeft | ze | die baan | aangeboden. | indirect object | |

| her brother/him | has | she | that job | prt.-offered | |||

| 'Her brother/Him, she has offered that job.' | |||||||

There are, however, two important differences between subject-initial sentences and sentences with an object in first position. First, clause-initial objects can be considered to be semantically marked in that they act as discourse topics or contrastive foci, or have some other special function in the organization of the discourse, while this does not necessarily hold for clause-initial subjects. Second, topicalized objects are often characterized by a special intonation pattern: the objects in (286b&c), but not the clause-initial subjects in (286a), must be accented, as is clear from the fact the latter but not the former can be a reduced pronoun. This suggests that subject-initial sentences may also be syntactically different from constructions with topicalized objects; we will return to this issue in Subsection III.

Next, the examples in (287) show that it is also possible to topicalize prepositional objects: (287a) illustrates this for a prepositional indirect object and (287b) for the prepositional object of kijken (naar)'to look (at)'.

| a. | Aan haar broer/Hem | heeft | ze | die baan | aangeboden. | indirect object | |

| to her brother/him | has | she | that job | prt.-offered | |||

| 'His her brother/him, she has offered that job to.' | |||||||

| b. | Naar dat huis | staat | Jan al | een uur te kijken. | prepositional object | |

| at that house | stands | Jan already | an hour to look | |||

| 'That house, Jan has been staring at for an hour.' | ||||||

Complementives can also be topicalized: we illustrate this in (288) by means of three examples with complementives of a different categorial status; they show that noun phrases, APs and PPs can all be topicalized.

| a. | Een liefhebber van Jazz | ben | ik | niet | echt. | nominal | |

| a devotee of jazz | am | I | not | really | |||

| 'A devotee of jazz, I am not really.' | |||||||

| b. | Aardig | is de nieuwe directeur | beslist. | adjectival | |

| nice | is the new director | definitely | |||

| 'Nice, the new director definitely is.' | |||||

| c. | In de la | heb | ik | de schaar | gelegd. | adpositional | |

| into the drawer | have | I | the scissors | put | |||

| 'In the drawer, I have put the scissors.' | |||||||

Adjuncts can also be topicalized. Example (289a) shows this for supplementives and examples (289b&c) for adverbial phrases. Observe that we did not mark the adverbial phrases for accent; assigning accent is possible but does not seem to be necessary. We will return to this issue in Subsection IV.

| a. | Kwaad | liep | hij | weg. | supplementive | |

| angry | walked | he | away | |||

| 'Angry, he walked away.' | ||||||

| b. | Op zolder | slapen | de kinderen. | place adverbial | |

| on attic | sleep | the children | |||

| 'In the attic, the children sleep/are sleeping.' | |||||

| c. | Na de vergadering | vertrekken | we. | time adverbial | |

| after the meeting | leave | we | |||

| 'After the meeting, we will leave.' | |||||

The discussion above has shown that topicalization is like wh-question formation in that constituents with various syntactic functions (argument, complementive and adjunct) and of various different forms (noun phrase, AP and PP) can be moved into sentential-initial position. Topicalization differs from wh-movement, however, in that it also allows preposing of clauses; this is illustrated in (290) for a finite clause. We return to topicalization of clauses in Subsection VI. Accent can be assigned at various places within the preposed clause.

| a. | Ik | verwacht | niet | [dat | hij | dat boek | wil | hebben]. | |

| I | expect | not | that | he | that book | wants | have | ||

| 'I don't expect that he wants to have that book.' | |||||||||

| b. | [Dat hij dat boek wil hebben] verwacht ik niet. |

The examples in (291) show that it is also possible to topicalize the complement of perfect and passive auxiliaries, a phenomenon known as VP-topicalization. The (a)-examples show that topicalization of the participle is possible both with and without the direct object; the (b)-examples show that subjects are normally not affected. VP-topicalization will also be discussed in Subsection VI. Accent will normally be assigned to the object if it is pied piped by VP-topicalization.

| a. | Ze | hebben | mijn huis | nog | niet | geschilderd. | perfect | |

| they | have | my house | yet | not | painted | |||

| 'They haven't painted my house yet.' | ||||||||

| a'. | [<Mijn huis> geschilderd] hebben ze <mijn huis> nog niet. |

| b. | Mijn huis | wordt | volgend jaar | geschilderd. | passive | |

| my house | be | next year | painted | |||

| 'My house will be painted next year.' | ||||||

| b'. | Geschilderd wordt mijn huis volgend jaar. |

Topicalization involves movement of some constituent into the initial position of the main clause. It resembles the formation of wh-questions in that the movement targets the position immediately preceding the finite verb; this is illustrated again in the (b)-examples in (292). This observation is not trivial; this does not hold for a language like English. We return to this in Subsection VII.

| a. | Jan | heeft | gisteren | dat boek | gelezen. | |

| Jan | has | yesterday | that book | read | ||

| 'Jan read that book yesterday.' | ||||||

| b. | Welk boeki | heeft | Jan gisteren ti | gelezen? | wh-question | |

| which book | has | Jan yesterday | read | |||

| 'Which book did Jan read yesterday?' | ||||||

| b'. | Dat boeki | heeft | Jan gisteren ti | gelezen. | topicalization | |

| that book | has | Jan yesterday | read | |||

| 'That book, Jan read yesterday.' | ||||||

The (b)-examples in (293) show that topicalization differs from question formation (and relativization) in that it is a root phenomenon. It cannot apply in embedded clauses.

| a. | Marie zei | [dat | Jan | dat boek | gelezen | heeft]. | |

| Marie said | that | Jan | that book | read | has | ||

| 'Marie said that Jan has read that book.' | |||||||

| b. | Marie vroeg | [welk boeki | Jan ti | gelezen | heeft]. | wh-question | |

| Marie asked | which book | Jan | read | has | |||

| 'Marie asked which book Jan has read.' | |||||||

| b'. | * | Marie zei | [dat boeki | Jan ti | gelezen | heeft]. | topicalization |

| Marie said | that book | Jan | read | has |

There is no way in which embedded topicalization in examples such as (293b') can be improved. The examples in (294), for instance, show that Dutch does not have the option found in German to have topicalization in embedded clauses with verb-second, as embedded verb-second is categorically prohibited in Dutch. We refer the reader to Haider (1985/2010) and Barbiers (2005: Section 1.3.1.8) for a discussion of embedded verb-second in, respectively, German and a number of non-standard varieties of Dutch; the German example in (294a) is taken from Müller (1998:42) in a slightly adapted from.

| a. | Marie | sagte | [dieses Buchi | habeconjunctive | sie ti | bereits | gelesen]. | German | |

| Marie | said | this book | has | she | already | read | |||

| 'Marie said that this book, she had already read.' | |||||||||

| b. | * | Marie | zei | [dit boeki | had | ze ti | al | gelezen]. | Dutch |

| Marie | said | this book | had | she | already | read |

The examples in (294) also show that embedded topicalization cannot occur with a phonetically expressed complementizer, unlike what is the case in English examples such as (295a); cf., e.g., Chomsky (1977), Baltin (1982) and Lasnik & Saito (1992). Since there is no a priori reason to think that Dutch topicalization targets a different position than English topicalization, we have added example (295b'), in which the complementizer dat'that' precedes the topicalized phrase.

| a. | Marie thinks [that this booki you should read ti ]. | English |

| b. | * | Marie denkt | [dit boeki | dat | je | zou ti | moeten | lezen]. | Dutch |

| Marie thinks | this book | that | you | would | must | read |

| b'. | * | Marie denkt | [dat | dit boeki | je ti | zou | moeten | lezen]. | Dutch |

| Marie thinks | that | this book | you | would | must | read |

Examples (296a&b) show that topicalization is like question formation in that it allows long wh-movement if a bridge verb such as denken'to think' is present. It should be noted, however, that long topicalization is like relativization in that it is possible with a wider range of verbs than question formation; cf. Schippers (2012:105). For instance, the factive verb weten'to know' permits long topicalization (and long relativization), but not long wh-movement. It should further be noted that some speakers prefer the resumptive prolepsis construction in (296c) to the somewhat marked long topicalization construction in (296b).

| a. | Welk boeki | denk/*weet | je | [dat | Jan ti | gekocht | heeft]? | wh-question | |

| which book | think/know | you | that | Jan | bought | has | |||

| 'Which book do you think that Jan has bought?' | |||||||||

| b. | (?) | Dit boeki | denk/weet | ik | [dat | Jan ti | gekocht | heeft]. | topicalization |

| this book | think.know | I | that | Jan | bought | has | |||

| 'This book I think/know that Jan has bought.' | |||||||||

| c. | Van dit boeki | denk/weet | ik | [dat | Jan heti | gekocht | heeft]. | prolepsis | |

| of this book | think/know | I | that | Jan it | bought | has | |||

| 'As for this book, I think/know that Jan has bought it.' | |||||||||

That topicalization involves wh-movement is also suggested by the fact that it is island-sensitive, just like question formation and relativization. We illustrate this in (297b) by means of an embedded polar question. For completeness' sake, we have added (297b') to show that the intended meaning can be expressed by means of a resumptive prolepsis construction.

| a. | Ik | vraag | me | af | [of | Jan dat boek | gekocht | heeft]? | |

| I | wonder | refl | prt. | if | Jan that book | bought | has | ||

| 'I wonder whether Jan has bought that book.' | |||||||||

| b. | * | Dat boeki | vraag | ik | me | af | [of | Jan ti | gekocht | heeft]? |

| that book | wonder | I | refl | prt. | if | Jan | bought | has |

| b'. | Van dat boeki | vraag | ik | me | af | [of | Jan heti | gekocht | heeft]? | |

| of that book | wonder | I | refl | prt. | if | Jan it | bought | has | ||

| 'As for this book, I am wondering whether Jan has bought it.' | ||||||||||

Example (298b) illustrates the island-sensitivity of topicalization by means of an adjunct island. In this case, the resumptive prolepsis construction is not available as an alternative because the verb huilen'to cry' does not license a resumptive van-PP.

| a. | Jan huilt | [omdat | Marie dat boek | gestolen | heeft]. | |

| Jan cries | because | Marie that book | stolen | has | ||

| 'Jan is crying because Marie has stolen that book.' | ||||||

| b. | * | Dat boeki | huilt Jan [omdat | Marie ti | gestolen | heeft]. |

| that book | cries Jan because | Marie | stolen | has |

This subsection has shown that topicalization exhibits various hallmarks of wh-movement: it targets the clause-initial position, it can be extracted from clauses selected by bridge verbs and it is island-sensitive. What sets it apart from wh-movement and relativization is that it is a root phenomenon; it cannot target the initial position of embedded clauses. We refer to Hoekstra & Zwart (1994), Sturm (1996) and Zwart & Hoekstra (1997) for a discussion of the question as to whether this shows that topicalization targets a different position than wh-movement, as in fact would be claimed in the cartographic approach initiated by Rizzi (1997).

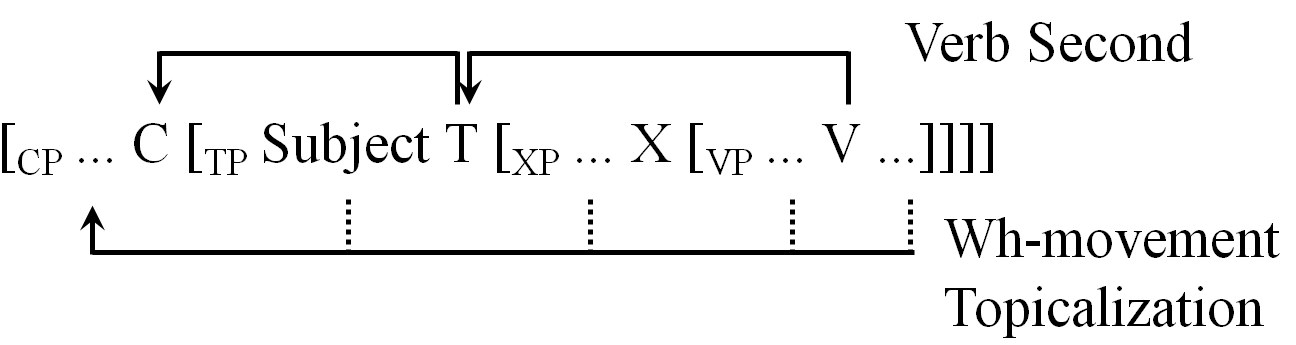

The standard view in generative grammar is that topicalization is responsible for verb second in declarative main clauses in Dutch. The verb is first moved into the C-position immediately preceding the canonical subject position, after which the specifier position of CP is filled by some topicalized phrase. This implies that subject-initial main clauses such as (299a) must be derived by topicalization, as indicated in the representation in (299b).

| a. | Mijn zuster/Zij/Ze | heeft | dit boek | gelezen. | subject | |

| my sister/she/she | has | this book | read | |||

| 'My sister/she has read this book.' | ||||||

| b. |  |

If the derivation in (299) is correct, we would expect the placement of subjects to be subject to similar restrictions as other cases of topicalization, like in the examples in (300). We seen in Subsection I, however, that subjects crucially differ from objects in that they need not be accented. The effect is even more conspicuous with weak (phonetically reduced) pronouns; while (299a) shows that the weak subject pronoun ze 'she' is fully acceptable in sentence-initial position, weak object pronouns like 'r 'her' in (300a&b) are not because they cannot be accented; see, e.g., Bouma (2008:34) for more discussion. Adverbial PPs with a weak pronominal complement can be topicalized if the preposition can be assigned accent; see Salverda (2000).

| a. | Mijn zuster/Haar/*'r | heb | ik | nog niet | gezien. | direct object | |

| my sister/her/her | have | I | yet not | seen | |||

| 'My sister/her I haven't seen yet.' | |||||||

| b. | Op mijn zuster/haar/*'r | wil ik niet wachten. | PP-object | |

| for my sister/her/her | want I not wait | |||

| 'My sister/Her I don't want to wait for.' | ||||

| c. | Naast 'r | zat | een aardige heer. | |

| next.to her | sat | a kind gentleman | ||

| 'Next to her sat a kind gentleman.' | ||||

The same contrast is found with the weak R-word er: the examples in (301) show that expletive er, which is normally assumed to occupy the regular subject position, can easily occur in sentence-initial position, but that this is excluded for er functioning as a locative pro-form or the pronominal part of a PP; topicalization is only possible with strong forms like daar'there' and hier'here'; see, e.g., Bouma (2008:29-30). We will ignore here that things are slightly complicated by the fact that (sentence-initial) er may sometimes have more than one function; we refer the reader to Section P5.5.3 for discussion and examples.

| a. | Er | spelen | veel kinderen | op straat. | expletive er | |

| there | play | many children | on street | |||

| 'There are many children playing in the street.' | ||||||

| b. | Daar/*Er | spelen | de kinderen | graag. | locative er | |

| there/there | play | the children | gladly | |||

| 'The children like to play there.' | ||||||

| c. | Daari/*Eri | wacht | ik | niet [ ti | op]. | pronominal part of PP | |

| there/there | wait | I | not | for | |||

| 'That I won't wait for.' | |||||||

That this contrast should have an impact on our syntactic analysis is clear from the fact illustrated in (302) that subject pronouns do exhibit a similar behavior as object pronouns if they are extracted from an embedded clause: whereas noun phrases like mijn zuster'my sister' and strong (phonetically non-reduced) subject pronouns such as zij give rise to a reasonably acceptable result, topicalization is excluded if the subject pronoun is weak.

| a. | (?) | Mijn zusteri/Ziji | zei | Jan | [dat ti | dit boek | gelezen | had]. |

| my sister/she | said | Jan | comp | this book | read | had | ||

| 'My sister/she, Jan said had read the book.' | ||||||||

| b. | * | Zei | zei | Jan [dat ti | dit boek | gelezen | had]. |

| she | said | Jan comp | this book | read | had |

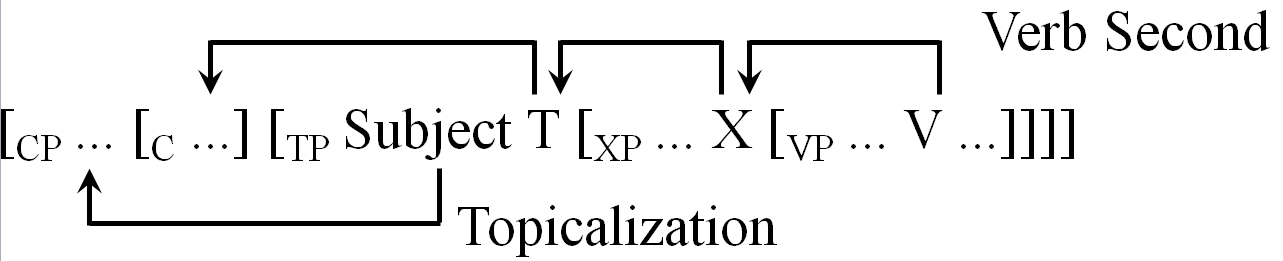

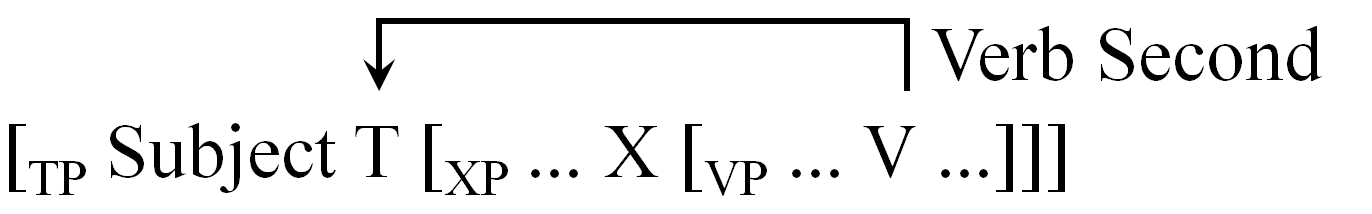

Section 9.3 concluded from this that regular subject-initial constructions do not involve topicalization but are derived by simply placing the subject in the regular subject position, the specifier of the T(ense) head. This resulted in the following derivations of subject-initial clauses and topicalization constructions; cf. Travis (1984) and Zwart (1992/1997). Note that these analyses suggest that subject-verb inversion is a hallmark of topicalization constructions; cf. Salverda (1982/2000).

| a. | Subject-initial sentences | |

|

| b. | Topicalization constructions | |

|

Observe that we are not claiming here that subjects cannot be topicalized, but only that they are not topicalized if they occur in a neutrally pronounced sentence. Examples like (304a) with contrastive accent on the subject may involve topicalization. That they do so is strongly suggested by expletive constructions like (304b); since it is normally assumed that the expletive er'there' occupies the regular subject position, the subject niemand can only occur in sentence-initial position as a result of topicalization. We added the locational adverbial phrase op de vergadering to example (304b) to block a locative interpretation of er'there' in order to ensure that er indeed functions as an expletive.

| a. | Mijn zuster | heeft | dit boek | gelezen. | |

| my sister | has | this book | read | ||

| 'My sister/she has read this book.' | |||||

| b. | Niemand | was er | op de vergadering. | |

| nobody | was there | at the meeting | ||

| 'Nobody was there at the meeting.' | ||||

The analyses suggested in (303) are interesting in view of the fact that subject-initial clauses are the most neutral form of an utterance from a semantic view point: while topicalized phrases are special in that they play a specific role in structuring the discourse, sentence-initial subjects are often neutral in this respect. The representations in (303) thus enable us to express formally this by postulating that like question formation and relativization, topicalization is semantically motivated; see Dik (1978: Section 8.3.3), Haegeman (1995), Rizzi (1997), and many others. This will be the main topic of Subsection IV.

The information structure of a clause is closely related to its intonation pattern. In utterances like the (b)-examples in (305), which present new information only if intended as an answer to the question in (305a), the main accent is located at the end of the clause, normally on the constituent preceding the clause-final verbs; see Section 13.1, sub III, for more detailed discussion. We will refer to utterances with this intonation pattern as neutral clauses (in order to not complicate things we will discuss main clauses only).

| a. | Wat | is er | gebeurd? | |

| what | is there | happened | ||

| 'What has happened?' | ||||

| b. | Jan heeft | Marie | een brief | gestuurd. | |

| Jan has | Marie | a letter | sent | ||

| 'Jan has sent Marie a letter.' | |||||

| b'. | Jan heeft | een brief | naar Marie | gestuurd. | |

| Jan has | a letter | to Marie | sent | ||

| 'Jan has sent a letter to Marie.' | |||||

The intonation pattern of utterances can be affected by the information structure of the clause. In the primed examples in (306), which contain both presupposed and new information if used as answers to the questions in the primeless examples, the main accent must be located in the new information of the clause (henceforth: the new-information focus); in the cases at hand, this results in the placement of the main accent in a more leftward position. For more information about assignment of main accent in clauses we refer the reader to Booij (1995).

| a. | Wie heeft | Jan | een brief | gestuurd? | question | |

| who has | Jan | a letter | sent | |||

| 'Who has Jan sent a letter?' | ||||||

| a'. | Hij heeft | Marie | een brief | gestuurd. | answer | |

| Jan has | Marie | a letter | sent | |||

| 'He has sent Marie a letter.' | ||||||

| b. | Wat | heeft | Jan | naar Marie | gestuurd? | question | |

| what | has | Jan | to Marie | sent | |||

| 'What has Jan sent to Marie?' | |||||||

| b'. | Hij heeft | een brief | naar Marie | gestuurd. | answer | |

| Jan has | a letter | to Marie | sent | |||

| 'Jan has sent a letter to Marie.' | ||||||

The following subsections will show that topicalization may also affect the intonation pattern of utterances; we will see that the way in which the intonation pattern is affected depends on the impact topicalization has on the information structure of the clause. There are also a number of cases in which topicalization does not seem to have such a great impact on the intonation of the clause; we will discuss some of the prototypical cases. Before we start, we want to note that the literature exhibits a great deal of variation when it comes to information-structural notions like focus and topic; cf. Erteschik-Shir (2007) for an extensive review. We aim at staying close to the use of these notions in É. Kiss' (2002:ch.1-6) description of the Hungarian clause, in which these notions play a prominent role.

The new-information focus can also be placed in sentence-initial position as a result of topicalization. So, next to the answers in the primed examples in (306), we also find utterances like (307a&b). The parentheses indicate that the presuppositional part of such answers is normally omitted.

| a. | Marie | (heeft | hij | een brief | gestuurd). | answer to (306a) | |

| Marie | has | he | a letter | sent | |||

| 'Marie, he has sent a letter.' | |||||||

| b. | Een brief | (heeft | hij | naar Marie | gestuurd). | answer to (306b) | |

| a letter | has | he | to Marie | sent | |||

| 'A letter, he has sent to Marie.' | |||||||

Jansen (1981: Section 4.2.1) claims that focus topicalization of the type in (307) is not very frequent (in non-interrogative contexts), which raises the question as to whether we are simply dealing with new-information focus or whether utterances such as (307) have some additional property. We tend to think that the accents in these topicalization constructions are stronger than those in the primed examples in (306), which may suggest that topicalization constructions express contrastive or restrictive focus in the sense that the proposition holds for the focussed phrases, to the exclusion of any other referent; see Section 13.3.2 for more discussion.

This would be in line with the fact that utterance (307a) expresses that in the relevant domain of discourse only Marie was sent a book by Jan: if it were to turn out that Jan also sent a letter to Peter and that the speaker uttering (307a) was aware of that, he could be accused of not being fully informative by withholding information. The same would hold for utterance (307b) if it turned out that Jan also sent cocaine to Marie.

That we are dealing with restrictive focus is also supported by the fact that it is often impossible to topicalize non-specific indefinite noun phrases, as these are typically used for introducing new information but cannot easily be used in a contrastive or a restrictive fashion. Example (308a') shows, for example, that topicalization of the existential pronoun iemand gives rise to a highly marked result, and (308b') shows that topicalization of an indefinite noun phrase such as een pianist is restricted to cases in which the speaker contradicts a certain presupposition on the part of the addressee: it would be acceptable as a reaction to the following question: Hoe was je ontmoeting met die cellist gisteren?'How was your meeting with that cellist yesterday?'.

| a. | Ik | heb | gisteren | iemand | ontmoet. | |

| I | have | yesterday | someone | met | ||

| 'I met someone yesterday.' | ||||||

| a'. | ?? | Iemand heb ik gisteren ontmoet. |

| b. | Ik | heb | gisteren | een pianist | ontmoet. | |

| I | have | yesterday | a pianist | met | ||

| 'I met a pianist yesterday.' | ||||||

| b'. | # | Een pianist heb ik gisteren ontmoet. |

The negative pronoun niemand'nobody', on the other hand, can be topicalized in constructions such as (309a) if the speaker wants to express that he did expect to see in Amsterdam at least one person from the given domain of discourse. Similarly, example (309b) expresses that the speaker did not expect to be able to meet in Amsterdam all individuals in the given domain of discourse.

| a. | Niemand | heb | ik | in Amsterdam gezien | (zelfs | Jan | niet). | |

| nobody | have | I | in Amsterdam seen | even | Jan | not | ||

| 'Nobody, I have seen in Amsterdam (not even Jan).' | ||||||||

| b. | Iedereen | heb | ik | in Amsterdam | kunnen | ontmoeten | (zelfs | marie). | |

| everybody | have | I | in Amsterdam | can | meet | even | Marie | ||

| 'Everyone, I have been able to meet in Amsterdam (even Marie).' | |||||||||

Another indication that we are not dealing with mere new-information focus is that the topicalized phrase may be preceded by an (emphatic) focus particle like zelfs'even', alleen'solely', slechts/maar'only': cf. Barbiers (1995:ch.3).

| a. | Zelfs Marie | heeft | hij | een brief | gestuurd. | |

| even Marie | has | he | a letter | sent | ||

| 'He has even sent Marie a letter.' | ||||||

| b. | Alleen Marie | heeft | hij | een brief | gestuurd. | |

| only Marie | has | he | a letter | sent | ||

| 'Only Marie he has sent a letter.' | ||||||

| c. | Slechts twee studenten | haalden | het examen. | |

| only two students | passed | the exam | ||

| 'Only two students passed the exam.' | ||||

For want of more detailed information on the question as to whether topicalized focus phrases indeed necessarily express more than merely new information, we have to leave our suggestions above to future research.

The sentence-initial position is typically occupied by an aboutness topic, a phrase referring to an entity about which the sentence as a whole provides more information. Although the three examples in (311) express the same propositions, they provide additional information about completely different topics: in (311a) the topic is the subject Jan, in (311b) the topic is the direct object de brief'the letter', and in (311c) the topic is embedded in the complementive naar-PP. Observe that the comments in (311) typically contain new information and thus also contain sentence accent (which is again placed on the constituent preceding the clause-final verbs if the full comment consists of new information).

| a. | [topic | Jan] [comment | heeft | de brief | naar Marie | gestuurd]. | |

| [topic | Jan | has | the letter | to Marie | sent | ||

| 'Jan has sent the letter to Marie.' | |||||||

| b. | [topic | De brief] [comment | heeft | Jan naar Marie | gestuurd]. | |

| [topic | the letter | has | Jan to Marie | sent | ||

| 'The letter, Jan has sent to Marie.' | ||||||

| c. | [topic | Naar Marie] [comment | heeft Jan de brief gestuurd]. | |

| [topic | to Marie | has Jan the letter sent | ||

| 'To Marie, Jan has sent the letter.' | ||||

The new information in (311) is provided by an argument, but the examples in (312) show that this can also be an adverbial element that can be used contrastively, such as the negative adverb niet, which can be contrasted with the affirmative marker wel, or adverbs such as morgen'tomorrow', which can be contrasted with adverbs like vandaag'today' or nu'now'. For more examples, see Salverda (2000:100-1).

| a. | Peter | heb | ik | nog niet | gezien. | |

| Peter | have | I | not yet | seen | ||

| 'Peter, I haven't seen yet.' | ||||||

| b. | Het boek | moet | je | morgen | maar | lezen. | |

| the book | must | you | tomorrow | prt | read | ||

| 'The book, you should read tomorrow.' | |||||||

The aboutness topic is always part of the domain of discourse, which means that it must satisfy certain criteria: (i) it must be referential in the sense that it refers to an entity or set of entities and (ii) it must be specific, that is, the entity or set of entities must be identifiable in the domain of discourse. This implies that the aboutness topic is prototypically a proper noun, a referential personal pronoun, a definite noun phrase, a specific indefinite noun phrase, or a PP containing such a noun phrase; see É. Kiss (2002: chapter 2).

Contrastive topics differ from aboutness topics in that they need not be referential or specific; the examples in (313) show that they can be non-individual-denoting elements like bare plurals, indefinite noun phrases, adverbial phrases and verbal particles; examples such as (313a&b) are of course also possible with definite noun phrases (de zwaan/zwanen'the swan/swans') but this is not illustrated here. Contrastive topics are accented and followed by a brief fall in intonation on the following comment, which gives rise to a typical "hat" contour marked by the symbols "/" and "\". Contrastive topic constructions convey that there is an alternative topic for which an alternative comment holds (cf. É. Kiss 2002: Section 2.7); we made this explicit in the examples in (313) by adding the part within parentheses.

| a. | [topic | /Zwanen] [comment | \heb | ik | niet | gezien] | (maar | ganzen | wel). | |

| [topic | swans | have | I | not | seen | but | geese | aff | ||

| 'I haven't seen swans, but I did see geese.' | ||||||||||

| b. | [topic | / Een zwaan][comment | \heb | ik | niet | gezien] | (maar | wel | een gans). | |

| [topic | a swan | have | I | not | seen | but | aff | a goose | ||

| 'I haven't seen a swan, but I did see a goose.' | ||||||||||

| c. | [topic | /Omhoog] [comment | \ga ik | met de lift] | (maar | omlaag | via de trap). | |

| [topic | up | go I | by the elevator | but | down | via the stairs | ||

| 'Up I will use the elevator, but down I will take the stairs.' | ||||||||

| d. | [topic | /Tegen] [comment | \stemden | de socialisten] | (voor | de liberalen). | |

| [topic | against | voted | the socialists | for | the liberals. | ||

| 'The conservatives voted against (the bill), the liberals for.' | |||||||

The intonation pattern found in utterances like (313) is also possible with individual-denoting elements like the topics in (311). Applying the "hat" contour to these examples will result in similar contrastive readings as those in (313). For completeness' sake, note that examples such (313d) refute the persistent claim that verbal particles cannot be topicalized (cf., e.g., Zwart 2011:72); this is possible provided that they stand in opposition to another verbal particle (cf. Hoeksema 1991a) and thus allow a contrastive interpretation. We refer the reader to Section 13.3.2, sub II, for a more detailed discussion of contrastive topics.

The distal demonstrative pronouns die'that' and dat'that' are very common in sentence-initial position. These pronouns are used to refer to some referent in the immediately preceding context, as in example (314). We added indices in order to unambiguously indicate the intended interpretation of the pronoun. Topicalized demonstratives differ from the topicalized phrases discussed so far in that they need not have contrastive accent; see, e.g., Salverda (1982/2000) and Bouma (2008:45).

| a. | Heb | je | Jani | gezien? | Nee, | diei | is | ziek. | |

| have | you | Jan | seen | no | dem | is | ill | ||

| 'Did you see Jan? No, he is ill.' | |||||||||

The demonstrative can be accented, in which case it receives a contrastive/restrictive focus interpretation. If it remains unstressed, it typically indicates topic shift, that is, a change of aboutness topic. In this respect distal demonstratives differ crucially from referential personal pronouns like hij 'he' or zij 'she' , which typically refer to continuous topics. This is illustrated by means of the examples in (315); that the distal demonstrative brings about topic shift is clear from the fact that it cannot refer to the subject (the default topic) of the preceding sentence; referential pronouns are not subject to this restriction. We will not digress on topic shift here but refer the reader to Section N5.2.3.2, sub IIA1, for a more extensive discussion.

| a. | [Jani | ontmoette | Elsj ] | en | [hiji/*diei | vertelde | haarj | dat ... ] | |

| Jan | met | Els | and | he/dem | told | her | that |

| b. | [Jani | ontmoette | Elsj ] | en | [zej/diej | vertelde | hemi | dat ... ] | |

| Jan | met | Els | and | she/ dem | told | him | that |

Note further that distal demonstrative pro-forms like die'that' and dat'that' in sentence-initial position are often omitted in speech; we refer the reader to Section 11.2.2 for discussion of this.

The previous subsection has shown that unstressed demonstratives can be used to indicate a topic shift and are thus quite important for a smooth continuation of the discourse. Other topicalized elements with a similar function are connectives like daarom/dus'therefore', and desondanks'nevertheless', which are neither topical nor focal in nature but are simply used to indicate the relation between two successive sentences; cf. Salverda (1982).

| a. | [Marie is ziek] | en | [daarom | kan | ik | niet | komen]. | |

| Marie is ill | and | therefore | can | I | not | come | ||

| 'Marie is ill and therefore I cannot come.' | ||||||||

| b. | [Marie is ziek] | maar | [desondanks | zal | ik | komen]. | |

| Marie is ill | but | nevertheless | will | I | come | ||

| 'Marie is ill but nevertheless I will come.' | |||||||

The cases of topicalization discussed in the previous subsections are all functionally motivated by information-structural considerations or considerations related to the organization of discourse. There are, however, many cases in which it is not so clear what the functional motivation of topicalization would be. Consider the examples in (317): it has been claimed that the locational PP in (317a) must be interpreted contrastively and thus be assigned accent, whereas the locational PP in (317b) can be interpreted neutrally and thus be pronounced without any phonetic prominence.

| a. | In Utrecht | heeft | Marie haar broer | bezocht. | |

| in Utrecht | has | Marie her brother | visited | ||

| 'In Utrecht Marie has visited het brother.' | |||||

| b. | In Utrecht | is Els erg populair. | |

| in Utrecht | is Els very popular | ||

| 'In Utrecht, Els is still very popular.' | |||

This contrast between the two examples has been related to the semantic contribution of the PPs. The PP in (317a) is event-related in the sense that it is part of what is asserted: Marie has met Jan & this eventuality took place in Utrecht. This reading has the property that omission of the locational PP is possible without affecting the truth value of the assertion. The PP in (317b), on the other hand, is not event-related but is used to restrict the speaker's claim; this reading has the property that omission of the locational PP may affect the truth value of the assertion: from the fact that Els is popular in Utrecht we cannot infer that she is popular elsewhere. The contrast between the two examples in (318) shows that the difference between the two readings is associated with a difference in location of the PP in the middle field of the clause: while the PP can easily precede the subject in (318b), this gives rise to a marked result in (318a) (although the latter example improves if the subject is assigned contrastive accent). We refer to Maienborn (2001) for more detailed discussion.

| a. | dat | <??in Utrecht> | Marie <in Utrecht> | haar broer | bezocht | heeft. | |

| that | in Utrecht | Marie | her brother | visited | has | ||

| 'that Marie has visited her brother in Utrecht.' | |||||||

| b. | dat | <in Utrecht> | Els <in Utrecht> | erg populair | is. | |

| that | in Utrecht | Els | very popular | is | ||

| 'that in Utrecht Els is still very popular.' | ||||||

There is a wide range of (especially) adverbial phrases that are not directly event-related, and which may occur in sentence-initial positions with no or little emphasis; see Kooij (1978), Salverda (1982/2000) and Florijn (1992). These include at least certain restrictive temporal, modal, and speaker-related adverbials.

| a. | In de middeleeuwen | waren | heksen | heel gewoon. | restrictive temporal | |

| in the middle ages | were | witches | very common | |||

| 'In the Middle Ages, witches were very common.' | ||||||

| b. | Misschien | komt | Peter straks | nog. | modal | |

| maybe | comes | Peter later | prt | |||

| 'Maybe Peter will come later.' | ||||||

| c. | Helaas | kan | Peter niet | komen. | speaker-related | |

| unfortunately | can | Peter not | come | |||

| 'Unfortunately, Peter cannot come.' | ||||||

Examples of the type in (317b) and (319) are sometimes accounted for by introducing special mechanisms. Odijk (1995:section 2.1), for instance, proposes that adverbials like misschien'maybe' and helaas'unfortunately' can be base-generated in sentence-initial position. Alternatively, Frey (2006) claims in his discussion of similar German examples that all elements that may (optionally) precede the subject can be moved into the sentence-initial position simply in order to satisfy the V2-requirement; topicalization of such elements is thus predicted not to have any effect on the information structure of the clause. Frey claims that this is confirmed by the fact that dative objects can be topicalized without any special effect in passive and unaccusative constructions; the topicalized phrase in the primed examples in (320) should be able to receive a neutral interpretation in terms of information structure and should not require any special phonetic prominence.

| a. | dat | Peter/hem/'m | gisteren | een gratis maaltijd | werd | aangeboden. | |

| that | Peter/him/'m | yesterday | a free meal | was | prt-offered | ||

| 'that a free meal was offered to Peter/him yesterday.' | |||||||

| a'. | Peter/Hem/*'m | werd | gisteren | een gratis maaltijd | aangeboden. | |

| Peter/him/'m | was | yesterday | a free meal | prt.-offered | ||

| 'A free meal was offered to Peter/him yesterday.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Peter/hem/'m | die voorstelling | goed | bevallen | is. | |

| that | Peter/him/him | that show | well | pleased | is | ||

| 'that that show has pleased Peter/him a lot.' | |||||||

| b'. | Peter/Hem/*'m | is die voorstelling | goed | bevallen. | |

| Peter/him/him | is that show | well | pleased | ||

| 'That show has pleased Peter/him a lot.' | |||||

Although it does seem to be the case that the topicalized dative objects do not need any special emphasis, the primed examples nevertheless show that they differ from sentence-initial subjects in that they are not able to take the form of the weak pronoun 'm 'him' (see also Bouma 2008:26); this may be incompatible with Frey's claim. Because the judgments on the contrast between the two examples in (317) are subtle anyway, we have to leave it to future research to further investigate whether formal movement in the sense of Frey really exists; it might be interesting, for example, to see whether Frey's claim that the presumed cases of formal movement do not involve any form of prosodic prominence can be confirmed by an in-depth phonetic investigation.

Subsection IV has shown that topicalization is often semantically motivated. If we restrict ourselves to those forms of topicalization related to information-structure, we can say that topicalization may be used to create a focus-background, a topic-comment, or a topic-focus structure. As in the case of wh-question, we would expect that it would suffice to topicalize the focus/topic element, and this raises the question as to whether topicalization may trigger pied piping. It seems that we have to answer this question in the affirmative. Consider the question answer-pair in (321). We have seen that questions like (321a) involve pied piping: while movement of the interrogative pronoun wiens'whose' would in principle suffice to form the desired operator-variable chain, syntactic restrictions force movement of the complete noun phrase wiens boek'whose book'. Since the focus in the answer in (321b) corresponds to the wh-pronoun wiens we can immediately conclude that topicalization of a focus may trigger pied piping.

| a. | [Wiens boek]i | heb | je ti | gekocht? | |

| whose book | have | you | bought | ||

| 'Whose book have you bought?' | |||||

| b. | [Jans boek]i | heb | ik ti | gekocht | |

| Jan's book | have | I | bought | ||

| 'Jan's book, I have bought.' | |||||

The same can be illustrated by means of the question-answer pair in (322): while wh-movement of the nominal complement of the preposition op suffices in principle to create the desired operator-variable chain in (322a), the restrictions on preposition stranding in Dutch force movement of the complete PP op wie'for who'. As the focus in answer (322b) corresponds to the wh-phrase wie, this example again shows that topicalization of a focused phrase may trigger pied piping.

| a. | [Op wie]i | wacht | je ti? | |

| for who | wait | you | ||

| 'Who are you waiting for?' | ||||

| b. | [Op Jan]i | wacht | ik ti. | |

| for Jan | wait | I | ||

| 'Jan, I am waiting for.' | ||||

That pied piping depends on independent syntactic constraints can be seen once again by considering the question-answer pair in (323); the question in (323a) shows that stranding of prepositions is possible if the complement is an R-word like waar. The fact that the focused constituent de post'the post' must pied-pipe the preposition op shows that pied piping cannot be semantically motivated.

| a. | Waari | wacht | je [ti op]? | |

| where | wait | you | ||

| 'What are you waiting for?' | ||||

| b. | [Op de post]i | wacht | ik ti. | |

| for the post | wait | I | ||

| 'The mail, I am waiting for.' | ||||

The examples in (324) illustrate that topicalization of contrastively accented phrases may also trigger pied piping.

| a. | [[Jans boek]i | zal | ik ti | kopen] | (maar | Els' boek | niet). | |

| Jan's book | will | I | buy | but | Els' book | not | ||

| 'Jan's book I will buy, but Els' book I won't.' | ||||||||

| b. | [[Op Jan]i | zal | ik ti | wachten] | (maar | op Els niet). | |

| for Jan | will | I | wait | but | for Els not | ||

| 'Jan I will wait for, but I won't for Els.' | |||||||

| c. | Mijn moeder is 115 jaar, | maar | [zo oudi | [word | ik | echt | niet ti]]. | |

| my mother is 115 year | but | that old | become | I | really | not | ||

| 'My mother is 115 years old, but that old I really won't become.' | ||||||||

Although it is known that stranding and pied piping are relevant notions in the domain of topicalization (cf. Van Riemsdijk 1978), the literature normally focuses on wh-movement and relativization, because these allow us to investigate these phenomena without having to appeal to discourse; to our knowledge there is no detailed investigation of pied piping in topicalization contexts that takes information-structural considerations into account. We tend to think that there are not a great many differences vis-à vis question formation and relativization but this should be confirmed by a more careful investigation than we are able to conduct here.

Topicalization differs from question formation and relativization in that it allows wh-movement of certain types of clauses and other verbal projections. This difference is due to the fact that question formation and relativization normally affect some pronoun or other pro-form while topicalization affects full focus/topic phrases. This means that in the case of question formation and relativization the only way to get a clause in clause-initial position would be by pied piping, but this is prohibited across-the-board: wh-movement of a (part of a) clausal constituent is not able to pied-pipe the containing clause.

| a. | Wat | zei | hij? | Dat | hij | Peter niet gelooft. | question formation | |

| what | said | he | that | he | Peter not believes | |||

| 'What did he say? That he doesn't believe Peter.' | ||||||||

| b. | De opmerking | [die | me | hindert] | is | dat | hij Peter niet | gelooft. | relativization | |

| the remark | that | me | bothers | is | that | he Peter not | believes | |||

| 'The remark that bothers me is that he doesn't believe Peter.' | ||||||||||

| c. | [Focus/Topic | Dat | hij | Peter | niet | gelooft] | hindert | me. | topicalization | |

| [Focus/Topic | that | he | Peter | not | believes | annoys | me | |||

| 'That he doesn't believe Peter annoys me.' | ||||||||||

It is often claimed that constructions with a topicalized verbal projection (and argument clauses in particular) should be analyzed as left-dislocation constructions with a deleted (phonetically empty) resumptive pronoun; see Koster (1978) and Odijk (1998) for, respectively, a fairly early and a fairly recent discussion of this issue. This subsection will also consider whether the topicalization constructions discussed in this subsection have a corresponding left-dislocation construction in order to see whether this claim can be maintained, subsection A starts by discussing topicalization of (finite and infinitival) argument clauses, which is followed in Subsection B by a discussion of topicalization of adverbial clauses, subsection C addresses VP-topicalization, that is, topicalization of verbal complements of non-main verbs, subsection D summarizes some of the main finding and draws some general conclusions.

Chapter 5 has shown that there are various syntactic types of argument clauses. The main division is that between finite and non-finite clauses, and the latter can be subdivided further into om + te-infinitival, te-infinitival and bare infinitival clauses. We discuss these (sub)types in the following subsections.

The singly-primed examples in (326) show that finite subject and direct object clauses can readily be topicalized, and the doubly-primed examples show that such clauses may also appear in left-dislocated position, followed by the resumptive pronoun dat'that' in clause-initial position. These examples thus seem to support the hypothesis that topicalization constructions are left-dislocation constructions with a phonetically empty resumptive element. An additional argument in favor of this hypothesis is that the anticipatory pronoun het'it' in the primeless examples cannot be used in the singly-primed topicalization constructions. This would follow immediately if these constructions indeed contained a phonetically empty resumptive subject/object pronoun: the anticipatory pronoun het could then simply not appear for the same reason that it cannot appear in the doubly-primed examples—it cannot be assigned an independent syntactic function.

| a. | Het | hindert | me | [dat | hij | Peter | niet | gelooft]. | subject | |

| it | annoys | me | that | he | Peter | not | believes | |||

| 'It annoys me that he doesn't believe Peter.' | ||||||||||

| a'. | [Dat | hij | Peter | niet | gelooft] hindert (*het) me. |

| a''. | [Dat | hij | Peter | niet | gelooft], dat hindert me. |

| b. | Hij | betwistte | (het) | [dat hij te laat was]. | direct object | |

| he | disputed | it | that he too late was | |||

| 'He disputed (it) that he was late.' | ||||||

| b'. | [Dat hij te laat was] betwistte hij (*het). |

| b''. | [Dat hij te laat was], dat betwistte hij. |

Things are different in the case of verbs selecting a prepositional object. Even verbs that do not require an anticipatory pronominal PP to be present do not allow topicalization of the clause. Left dislocation, on the other hand, is fully acceptable.

| a. | Jan twijfelde | (erover) | [of | hij | het boek zou | kopen]. | PP-complement | |

| Jan doubted | about.it | if | he | the book would | buy | |||

| 'Jan doubted (about it) whether he would buy the book.' | ||||||||

| b. | * | [Of hij het boek zou kopen] twijfelde Jan (erover). |

| c. | [Of hij het boek zou kopen], daar twijfelde Jan over. |

Example (328) shows that omission of the pronominal part of the discontinuous PP daar ... over in example (327b) also gives rise to an unacceptable result for most speakers (although some speakers seem to accept it at a pinch). The impossibility of omitting daar poses a problem for the hypothesis that the topicalization constructions above are left-dislocation constructions with a phonetically empty resumptive element, and requires the introduction of some auxiliary hypothesis to regulate the deletion of resumptive pronouns.

| % | [Of | hij | het boek | zou | kopen] | twijfelde | Jan | over. | |

| whether | he | the book | would | buy | doubted | Jan | about |

Topicalization of finite argument clauses seems to be quite unrestricted. One exceptional case, taken from Odijk (1998), is given in (329). Although Odijk's judgment on (329b) is correct, it should be noted that example (329a) is an innovation in the language, as is clear from the fact that this use is not included in the latest (14th) edition of the Van Dale dictionary. Furthermore, many of our informants give an affirmative answer to the question as to whether (329a) should be considered an abbreviation of the more regular expression Jan belde om te zeggen dat hij ziek was ; compare the translation of (329a) which was taken from Odijk's article. We therefore provisionally conclude that topicalization of finite argument clauses is always possible.

| a. | Hij | belde | [dat | hij | ziek | was]. | |

| he | called | that | he | ill | was | ||

| 'He called to say that he was ill.' | |||||||

| b. | * | [Dat hij ziek was] belde hij. |

It less clear to what extent om + te- and te-infinitival clauses can be preposed. Koster (1987:129) claims for te-infinitivals that this is "often difficult" and subsequently assigns them an asterisk. Zwart (1993:263) presents a case of topicalization of a te-infinitive as fully acceptable, while Odijk (1995:12) claims that such cases "are always somewhat marginal"; in later work, Zwart (2011:112) assigns two question marks to both topicalized om + te- and te-infinitival clauses. We agree that topicalization of om + te- and te-infinitivals normally gives rise to a marked result, but we also feel that topicalization leads to a markedly worse result in the case of om + te-infinitivals; this is what we try to express by means of our diacritics on the two singly-primed examples in (330). The left-dislocation constructions in the doubly-primed examples seem fully acceptable (although speakers again seem to vary somewhat in their judgments). Observe that the contrast between the singly- and doubly-primed examples is unexpected on the hypothesis that topicalization constructions are left-dislocation constructions with a deleted (phonetically empty) resumptive pronoun.

| a. | Jani weigert | [(om) PROi | weg | te gaan]. | om + te-infinitival | |

| Jan refuses | comp | away | to go | |||

| 'Jan refuses to leave.' | ||||||

| a'. | *? | [(om) PROi weg te gaan] weigert Jani. |

| a''. | [(om) PROi weg te gaan], dat weigert Jani. |

| b. | Jani probeert | al | tijden [PROi | de auto | te repareren]. | te-infinitival | |

| Jan tries | already | ages | the car | to repair | |||

| 'Jan has been trying for ages to repair the car.' | |||||||

| b'. | ? | [PROi de auto te reparen] probeert Jani al tijden. |

| b''. | [PROi de auto te reparen], dat probeert Jani al tijden. |

The examples in (330) involve direct object clauses. In (331), we give similar examples with a verb selecting a prepositional object.

| a. | Jani klaagde | (erover) [PROi | niet | te kunnen | komen]. | |

| Jan complained | about.it | not | to be.able | come | ||

| 'Jan complained about not being able to come.' | ||||||

| b. | * | [PROi | niet | te kunnen | komen] klaagde Jani (erover). |

| c. | [PROi | niet | te kunnen | komen] daar klaagde Jani over. |

Example (332) shows that omission of the pronominal part of the discontinuous PP daar ... over in the left-dislocation construction (331b) gives rise to a quite marked result for most speakers. This is again problematic for the claim that topicalization constructions are left-dislocation constructions with a phonetically empty resumptive element.

| % | [Niet | te kunnen | komen] | klaagde | Jan over. | |

| not | to be.able | come | complained | Jan about |

The discussion above is typical for opaque and semi-transparent infinitival clauses which may occur in extraposed position; cf. Section 5.2.2.3. There are a number of additional, complicating issues for transparent te-infinitivals, that is, infinitivals that exhibit verb clustering and the infinitivus-pro-participio effect. However, because topicalization of te-infinitival normally gives rise to a marked result and we can discuss the same issues by means of fully acceptable cases in which a bare infinitival clause is topicalized, we will address these issues in the next subsection.

At first sight, topicalization of bare VPs seems easily possible, but closer scrutiny soon reveals that there are at least two complicating issues. The first issue is related to the fact that om general bare infinitival clauses are obligatorily split as a result of verb clustering. This phenomenon is illustrated in (333a) for the bare infinitival complement of the modal main verb willen'to want'. When we now consider the corresponding examples in (333b&c) notice to our surprise that clause splitting is optional (although we should note that dat hij graag die problemen oplossen wil is possible as a marked order). The primed examples are added to show that both topicalization constructions alternate with a left-dislocation counterpart, as predicted by the hypothesis that the topicalization constructions are left-dislocation constructions with a deleted (phonetically empty) resumptive pronoun.

| a. | dat | hij | <die problemen> | graag | wil <*die problemen> | oplossen. | |

| that | he | those problems | gladly | wants | prt.-solve | ||

| 'that he dearly to solve those problems.' | |||||||

| b. | Die problemen oplossen wil hij graag. |

| b'. | Die problemen oplossen, dat wil hij graag. |

| c. | Oplossen wil hij die problemen graag. |

| c'. | Oplossen, dat wil hij die problemen graag. |

A second problematical factor is related to the Infinitivus-Pro-Participio (IPP) effect. Example (334a) first shows that in perfect-tense constructions the matrix verb does not appear as a past participle but as an infinitive. The singly-primed examples in (334) show that the IPP-effect disappears in the topicalization constructions, regardless of whether the infinitival clause is split or not. The primed examples show the same for the corresponding left-dislocation constructions.

| a. | Hij | had | die problemen | graag | willen/*gewild | oplossen. | |

| he | had | those problems | gladly | want/wanted | prt.-solve | ||

| 'He had wanted to solve those problems very much.' | |||||||

| b. | Die problemen oplossen had hij graag gewild/*willen. |

| b'. | Die problemen oplossen, dat had hij graag gewild/*willen. |

| c. | Oplossen had hij die problemen graag gewild/*willen. |

| c'. | Oplossen, dat had hij die problemen graag gewild/*willen. |

The set of data in (333) and (334) thus shows that the core properties of constructions with transparent infinitives (clause splitting and IPP) disappear if the infinitival clause is topicalized. Although this has been known for a long time, there are still no theoretical accounts of it that meet with general acceptance. This is related to the current state of theories for these two phenomena. First, there are many competing theories on verb clustering that are more or less successful in describing the core data (see Section 7.5), but these are often quite different in nature and therefore also require quite different approaches to the (b)- and (c)-examples in (333). Second, there are only a few theories available for the IPP-effect, and most of these are highly controversial, so that we can at best conclude from the data in (334) that the IPP-effect only arises if the embedded main verb is physically located in the verbal cluster, a suggestion supported by examples such as (335), which show that the IPP-effect must be preserved if the full (non-finite part of the) verb cluster is topicalized.

| Willen/*Gewild | oplossen | had | hij | die problemen | graag. | ||

| want/wanted | prt.-solve | had | he | those problems | gladly | ||

| 'He had dearly wanted to solve those problems very much.' | |||||||