- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

Sections 2.1.2 and 2.1.3 discussed the so-called unaccusative verbs, that is, verbs taking an internal theme argument that surfaces as the subject of the clause. The derived subjects of these verbs have a thematic role similar to that of the direct object of a (di-)transitive clause, and behave in several respects like the subjects of passive constructions. One may wonder, however, whether there are also what we will call undative constructions, in which the derived subject is a recipient and hence corresponds to an indirect object in a ditransitive clause. Although this question has hardly been discussed in the literature, there are reasons for assuming that it should be answered in the affirmative.

We begin with the verb krijgen, which we will consider to be a prototypical instantiation of the undative verbs. Consider the examples in (128).

| a. | Jan gaf | Marie een boek. | |

| Jan gave | Marie a book |

| b. | Marie kreeg | een boek | (van Jan). | |

| Marie got | a book | of Jan | ||

| 'Marie received a book from Jan.' | ||||

In (128b) the subject has a role similar to that of the indirect object of geven'to give' in (128a): in both cases we seem to be dealing with a recipient argument. This suggests that the verb krijgen'to get' does not have an external argument (although the agent/cause can be expressed in a van-PP) and that the subject in (128b) is a derived one, which we will refer to an IO-subject. We will provide evidence in favor of this suggestion in the next subsections, but before we do that we want to note that the alternation in (128) also holds for particle verbs with geven and krijgen like teruggeven/terugkrijgen'to give/get back' or opgeven/opkrijgen in (129).

| a. | De leraar | gaf | de leerlingen | te veel huiswerk | op. | |

| the teacher | gave | the pupils | too much homework | prt. | ||

| 'The teacher gave his pupils too much homework.' | ||||||

| b. | De leerlingen | kregen | te veel huiswerk | op. | |

| the pupils | got | too much homework | prt. | ||

| 'The pupils got too much homework.' | |||||

If the subject in (128b) is indeed an internal recipient argument, we predict that er-nominalization of krijgen is excluded, since this process requires an external argument; cf. the generalization in (59a). Example (130a) shows that this prediction is indeed borne out. Note that krijgen differs in this respect from the verb ontvangen'to receive' which seems semantically close, but which has a subject that is more agent-like, that is, more actively involved in the event.

| a. | * | de krijger | van dit boek |

| the get-er | of this book |

| b. | de ontvanger | van dit boek | |

| the receiver | of this book |

Similarly, we expect the two verbs to behave differently in imperatives. The examples in (131) show that this expectation is indeed borne out.

| a. | We | krijgen/ontvangen | morgen | gasten. | |

| we | get/receive | tomorrow | guests | ||

| 'Weʼll get/receive guests tomorrow.' | |||||

| b. | Ontvang/*krijg | ze | (gastvrij)! | |

| receive/get | them | hospitably | ||

| 'Receive them hospitably.' | ||||

According to the generalization in (59d), the presence of an external argument is also a necessary condition for passivization, and this correctly predicts that passivization of (128b) is excluded. Again, krijgen differs from the verb ontvangen, which, contrary to what is claimed by Haeseryn et al. (1997), does allow passivization and must therefore be considered a regular transitive verb.

| a. | * | Het boek | werd | (door Marie) | gekregen. |

| the book | was | by Marie | gotten |

| b. | Het boek | werd | (door Marie) | ontvangen. | |

| the book | was | by Marie | received |

Although the facts in (130) and (132) are suggestive, they are not conclusive, since we know that not all unergative verbs allow er-nominalization and that there are several additional restrictions on passivization; cf. Section 3.2.1. There is, however, additional evidence that supports the idea that the subject of krijgen is a derived subject.

The idea that the subject of krijgen is a derived subject may also account for the fact that example (133a), which contains the more or less idiomatic double object construction iemand de koude rillingen bezorgen'to give someone the creeps', has the counterpart in (133b) with krijgen. This would be entirely coincidental if Jan would be an external argument of the verb krijgen, but follows immediately if it originates in the same position as the indirect object in (133a). For completeness' sake, observe that the more agentive-like verb ontvangen cannot be used in this context.

| a. | De heks | bezorgt | Jan de koude rillingen. | |

| the witch | gives | Jan the cold shivers | ||

| 'The witch gives Jan the creeps.' | ||||

| b. | Jan kreeg/*ontving | de koude rillingen | (van de heks). | |

| Jan got/received | the cold shivers | from the witch |

The most convincing argument in favor of the assumption that krijgen has an IO-subject is that it is possible for krijgen to enter inalienable possession constructions. In Standard Dutch, inalienable possession constructions require the presence of a locative PP like op de vingers in (134a). The nominal part of the PP refers to some body part and the possessor is normally expressed by a dative noun phrase: (134a) expresses the same meaning as (134b), in which the possessive relation is made explicit by means of the possessive pronoun haar'her'. We refer the reader for a more detailed discussion of this construction to Section 3.3.1.4.

| a. | Jan | gaf | Marie | een tik | op de vingers. | |

| Jan | gave | Marie | a slap | on the fingers | ||

| 'Jan gave Marie a slap on her fingers.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan | gaf | Marie | een tik | op haar vingers. | |

| Jan | gave | Marie | a slap | on her fingers | ||

| 'Jan gave Marie a slap on her fingers.' | ||||||

Subjects of active constructions normally do not function as inalienable possessors: an example such as (135a) cannot express a possessive relationship between the underlying subject Jan and the nominal part of the PP, as a result of which the example is pragmatically weird (unless the context provides more information about the possessor of the body part). In order to express inalienable possession the simplex reflexive object pronoun zich must be added, as in (135b).

| a. | ?? | Jan | sloeg | op de borst. |

| Jan | hit | on the chest |

| b. | Jan | sloeg | zich | op de borst. | |

| Jan | hit | refl | on the chest | ||

| 'Jan tapped his chest.' | |||||

Note that the reflexive pronoun in (135b) is most likely assigned dative case (and not accusative). Of course, this cannot be seen by inspecting the form of the invariant reflexive in (135b) but it can be made plausible by inspecting the structurally parallel German examples in (136) where the possessor appears as a dative pronoun; see Broekhuis et al. (1996) for detailed discussion.

| a. | Ich | boxe | ihmdat | in den Magen. | |

| I | hit | him | in the stomach | ||

| 'I hit him in the stomach.' | |||||

| b. | Ich | klopfe | ihmdat | auf die Schulter. | |

| I | pat | him | on the shoulder | ||

| 'I patted his shoulder.' | |||||

The subject of the verb krijgen is an exception to the general rule that subjects of active constructions do not function as inalienable possessors, as is clear from the fact that the subject Marie in (137a) is interpreted as the inalienable possessor of the noun phrase de vingers. This would again follow immediately if we assume (i) that inalienable possessors must be internal recipient arguments, and (ii) that subject Marie (137a) is not an underlying subject but a derived IO-subject. Example (137b) is added to show that, just as in (134), the inalienable possession relation can be made explicit by means of the possessive pronoun haar'her'.

| a. | Marie | kreeg | een tik | op de vingers. | |

| Marie | got a | slap | on the fingers |

| b. | Marie | kreeg | een tik | op haar vingers. | |

| Marie | got | a slap | on her fingers |

A Google search shows that the verb krijgen again differs from the more agentive-like verb ontvangen. The number of hits for the string [V een tik op de vingers], with one of the present or past-tense forms of the verb krijgen resulted in numerous hits, whereas there was not a single hit for the same string with one of the present or past forms of the verb ontvangen.

To conclude, it may be useful to observe that the possessive dative examples in (134) and (137) all allow an idiomatic reading comparable to English to give someone/to get a rap on the knuckles, that is, "to reprimand/be reprimanded"; compare the discussion of the examples in (133).

The idea that krijgen is an undative verb is interesting in view of the fact that it is also used as the auxiliary in the so-called krijgen-passive, in which it is not the direct but the indirect object that is promoted to subject. Consider the examples in (138): example (138b) is the regular passive counterpart of (138a), in which the direct object is promoted to subject; example (138c) is the krijgen-passive counterpart of (138a), and involves promotion of the indirect object to subject.

| a. | Jan bood | Marie het boek | aan. | |

| Jan offered | Marie the book | prt. |

| b. | Het boek | werd Marie | aangeboden. | |

| the book | was Marie | prt.-offered | ||

| 'The book was offered to Marie.' | ||||

| c. | Marie kreeg | het boek | aangeboden | |

| Marie got | the book | prt.-offered | ||

| 'Marie was offered the book.' | ||||

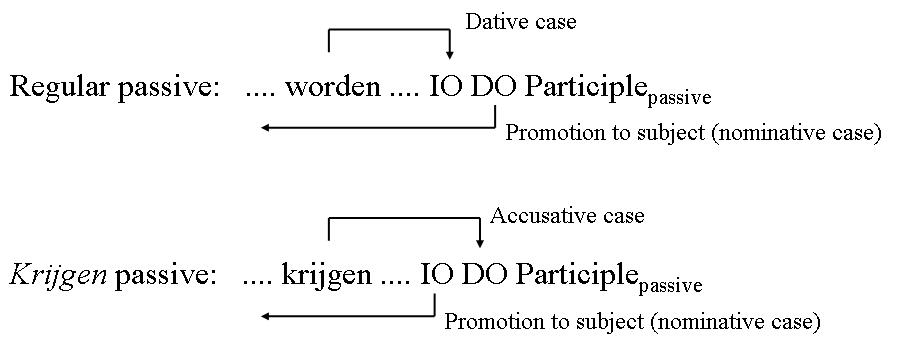

The obvious question that the passive constructions in (138b&c) raise is what determines which of the two internal arguments is promoted to subject. Given the fact that worden is clearly an unaccusative verb (for example, it takes the auxiliary zijn in the perfect tense), the hypothesis that krijgen is an undative verb suggests that it is the auxiliary verb that is responsible for that: if the auxiliary is an unaccusative verb, the direct object of the corresponding active construction cannot be assigned accusative case and must hence be promoted to subject; if the auxiliary is an undative verb, on the other hand, the indirect object cannot be assigned dative case and must therefore be promoted to subject. If we assume that passive participles are not able to assign case (see Section 3.2.1), case assignment in the two types of passive construction will take place, as indicated in Figure 1.

The discussion in the previous subsection strongly suggests that main verb krijgen is a representative of a verb type that can be characterized as undative. This subsection shows that the verbs hebben'to have' and houden'to keep' exhibit very similar syntactic behavior to krijgen, and are thus likely to belong to the same verb class. But before we do this, we want to discuss one important difference between krijgen, on the one hand, and hebben and houden, on the other.

The contrast between (139a) and (139b-c) shows that krijgen but not hebben and houden, may take a van-PP that seems to express an agent. Note that we have added a percentage mark to (139b) in order to express that some speakers do accept this example with the van-PP, albeit that in that case the meaning of hebben shifts in the direction of krijgen; a more or less idiomatic example of this type is Marie heeft dat trekje van haar vader'Marie has inherited this trait from her father'.

| a. | Marie kreeg | het boek | (van JanAgent). | |

| Marie got | the book | from Jan |

| b. | Marie heeft | het boek | (%van JanAgent). | |

| Marie has | the book | from Jan |

| c. | Marie houdt | het boek | (*van JanAgent). | |

| Marie keeps | the book | from Jan |

The contrasts in (139) may be related to the meanings expressed by the three verbs: the construction with krijgen in (139a) expresses that the theme het boek has changed position with the referent of the complement of the van-PP referring to its original, and the subject of the clause referring to its new location. This suggests that the van-PPs express not only the agent but also the source. If so, the fact that the agentive van-PP is not possible in the construction with hebben in (139b) may be due to the fact that this verb does not denote transfer, but expresses possession. Something similar holds for the construction with houden'to keep' in (139c), which explicitly expresses that transfer of the theme is not in order.

This subsection discusses data that suggest that hebben is an undative verb on a par with krijgen. The first thing to note is that hebben does not allow er-nominalization. In this respect, hebben differs from the verb bezitten, which is semantically very close to it. The contrast between (140a) and (140b) may again be related to the fact that the subject of the latter is more agent-like. For example, whereas the verb hebben can be used in individual-level predicates like grijs haar hebben'to have grey hair' or in non-control predicates like de griep hebben'to have flu', the verb bezitten cannot: Jan heeft/*bezit grijs haar'Jan has grey hair'; Jan heeft/*bezit de griep'Jan is having flu'.

| a. | * | een | hebber | van boeken |

| a | have-er | of books |

| b. | een | bezitter | van boeken | |

| an | owner | of books | ||

| 'an owner of books' | ||||

For completeness' sake, note that there is a noun hebberd, which is used to refer to greedy persons. This noun is probably lexicalized, which is clear not only from the meaning specialization but also from the facts that it is derived by means of the unproductive suffix -erd and that it does not inherit the theme argument of the input verb: een hebberd (*van boeken).

Second, hebben is like krijgen in that it cannot be passivized. Note that this also holds for the verb bezitten, which was shown in (140b) to be a regular transitive verb. This shows that passivization is not a necessary condition for assuming transitive status for a verb.

| a. | * | Het boek | werd | (door Marie) | gehad. |

| the book | was | by Marie | had |

| b. | ?? | Het boek | werd | (door Marie) | bezeten. |

| the book | was | by Marie | owned |

Third, alongside the idiomatic example in (133), we find example (142) with a similar meaning. This would be coincidental if the subject were an external argument of the verb hebben, but is expected if it is an IO-subject.

| Jan heeft | de koude rillingen | (??van de heks). | ||

| Jan has | the cold shivers | from the witch | ||

| 'Jan has got the creeps.' | ||||

Finally, like the subject of krijgen, the subject of hebben can be used as an inalienable possessor of the nominal part of a locative PP. This would again follow if we assume (i) that inalienable possessors must be recipient arguments and (ii) that subject Peter in (143b) is an IO-subject.

| a. | Jan stopt | Peter | een euro | in de hand. | |

| Jan puts | Peter | a euro | in the hand | ||

| 'Jan is putting a euro in Peterʼs hand.' | |||||

| b. | Peter heeft | een euro | in de hand. | |

| Peter has | a euro | in the hand | ||

| 'Peter has a euro in his hand.' | ||||

The verb houden'to keep' in (144a) seems to belong to the same semantic field as hebben'to have' and krijgen'to get', but expresses that transmission of the theme argument does not take place. Examples (144b) and (144c) show, respectively, that er-nominalization and passivization are excluded, and (144d) shows that the subject of this verb may act as an inalienable possessor.

| a. | Marie houdt de boeken. | |

| Marie keeps the books |

| b. | * | een houder | van boeken |

| a keeper | of books |

| c. | * | De boeken | worden | gehouden. |

| the books | are | kept |

| d. | Mao | hield | een rood boekje | in de hand. | |

| Mao | kept | a red bookdiminutive | in the hand | ||

| 'Mao held a little red book in his hand.' | |||||

There are, however, several problems with the assumption that houden is an undative verb. First, there are cases of er-nominalization such as (145b). These cases are special, however, because the corresponding verbal construction does not occur, and we therefore conclude that we are dealing with (commonly used) jargon.

| a. | * | Jan houdt een OV-jaarkaart van de NS. |

| Jan keeps an annual commutation ticket | ||

| Intended meaning: 'Jan has an annual commutation ticket.' |

| b. | houders van een OV-jaarkaart van de NS | |

| keepers of an annual commutation ticket |

Second, the (a)-examples in (146) show that there are constructions with houden that do allow passivization; this deviant behavior of these examples may be due to the fact that we are dealing with an idiomatic expression with more or less the same meaning as the transitive verb bespieden'to spy on', which likewise allows passivization. Note in passing that the corresponding construction with krijgen behaves as expected and does not allow passivization.

| a. | De politie | hield | de man | in de gaten. | gaten probably refers to eyes | |

| the police | kept | the man | in the gaten | |||

| 'The police were keeping an eye on the man.' | ||||||

| a'. | De man | werd | door de politie | in de gaten | gehouden. | |

| the man | was | by the police | in the gaten | kept | ||

| 'The man was being watched by the police.' | ||||||

| b. | De politie | kreeg | de man | in de gaten. | |

| the police | got | the man | in the gaten | ||

| 'The police noticed the man.' | |||||

| b'. | * | De man werd | door de politie | in de gaten | gekregen. |

| the man was | by the police | in the gaten | got |

Third, er-nominalization and passivization are possible with the verb houden when this verb is used in reference to livestock, as in (147). The fact that the object in (147a) can be a bare plural (or a mass noun) suggests, however, that we are dealing in this case with a semantic (that is, syntactically separable) compound verb comparable to particle verbs (although it should be noted that the bare noun can be replaced by quantified indefinite noun phrases like veel schapen'many sheep').

| a. | Jan houdt schapen/*een schaap. | |

| Jan keeps sheep/a sheep | ||

| 'Jan is keeping sheep' |

| b. | schapenhouder 'sheep breeder' |

| c. | Er | worden | schapen | gehouden. | |

| there | are | sheep | kept |

The class of undative verbs has not been extensively studied so far, and it is therefore hard to say anything with certainty about the extent of this verb class. Although this is certainly a topic for future research, we will briefly argue that verbs of cognition like weten'to know' and kennen'to know' in (148a), in which the subject of the clause acts not as an agent but as an experiencer, may also belong to this class. One argument in favor of assuming that these verbs are undative is that the thematic role of experiencer is normally assigned to internal arguments; see the discussion of the nom-dat verbs in Section 2.1.3. A second argument is that these verbs normally do not allow passivization, as is shown in (148b).

| a. | Jan weet/kent | het antwoord. | |

| Jan knows | the answer | ||

| 'Jan knows the answer.' | |||

| b. | * | Het antwoord | wordt | (door Jan) | geweten/gekend. |

| the answer | is | by Jan | known |

Note in passing that passives like these do occur in more or less formal contexts, in which case the subject is most likely a human being: Jezus kan uitsluitend echt gekend worden door iemand die de juiste geesteshouding heeft' 'Jesus can only be known by someone who has the right spiritual attitude'. It also occurs in collocations like gekend worden als'to be known as' and gekend worden in'to be consulted'.

Er-nominalizations also seem to suggest that cognitive verbs are undative. Although the er-noun kenner in (149a) does exist, it does not exhibit the characteristic property of productively formed er-nouns that they inherit the internal argument of the input verb. Furthermore, it has the highly specialized meaning "expert". The er-noun weter in (149b) does not exist at all (although it does occur as the second member in the compounds allesweter'someone who knows everything' and betweter'know-it-all'). The fact that these verbs normally do not occur in the imperative shows that the input verbs do not have an agentive argument and therefore point in the same direction as well; see Section 1.4.2, sub IA for a discussion of the counterexample Ken uzelf!'Know yourself!'.

| a. | de | kenner | (*van het antwoord) | |

| the | know-er | of the answer | ||

| 'the expert' | ||||

| a'. | * | Ken | het antwoord! |

| know | the answer |

| b. | * | de | weter | (van het antwoord) |

| the | know-er | of the answer |

| b'. | * | Weet | het antwoord! |

| know | the answer |

Finally, the examples in (150) show that the subjects of these verbs may enter into a possessive relationship with the nominal part of a locative PP, which is probably the strongest evidence in favor of assuming undative status for these verbs. It further suggests that, like the thematic role recipient, the thematic role experiencer cannot be assigned to an external argument, but must be assigned to an internal argument that corresponds to the dative argument of a ditransitive verb.

| a. | Jan kent | het gedicht | uit het/zijn hoofd. | |

| Jan knows | the poem | from the/his head | ||

| 'Jan knows the poem by heart.' | ||||

| b. | Jan weet | het | uit het/zijn hoofd. | |

| Jan knows | it | from the/his head | ||

| 'Jan knows it like that.' | ||||

Other potential examples of undative verbs are behelzen'to contain/include', bevatten'to contain', inhouden'to imply', and omvatten'to comprise'. These verbs may belong to the same semantic field as hebben and Haeseryn et al. (1997:54) note that these verbs are similar to hebben in rejecting passivization. It is, however, not clear whether the impossibility of passivization is very telling in these cases given that many of these verbs take inanimate subjects, for which reason they of course also resist the formation of person nouns by means of er-nominalization.

- 1996Inalienable possession in locational constructions; some apparent problemsCremers, Crit & Den Dikken, Marcel (eds.)Linguistics in the Netherlands 1996Amsterdam/PhiladelphiaJohn Benjamins37-48

- 1997Algemene Nederlandse spraakkunstGroningenNijhoff

- 1997Algemene Nederlandse spraakkunstGroningenNijhoff