- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

Inherent prepositions are interpreted in relation to the dimensional properties of the reference object (the complement of the preposition). The four subsets in (215) can be distinguished; these will be discussed in the following subsections.

| a. | Prepositions that denote a set of vectors that situate the located object: | |

| (i) relative to the dimensions mentally attributed to the reference object: achter'behind', naast'next to', voor'in front of' and tegenover'opposite' | ||

| (ii) relative to the physical dimensions of the reference object: langs'along', binnen'within/inside', buiten'outside', bij'near' |

| b. | Prepositions that denote the null vector: | |

| (i) the located object is (partly) in the reference object: in'in', uit'out of', door'through' | ||

| (ii) the located object is in contact with the reference object: aan'on', op'on', over (II) 'over', tegen'against' |

The two sets of prepositions that belong to this group situate the located object with respect to the reference object, without implying that there is physical contact between the two. Two groups can be distinguished: prepositions that situate the located object with respect to the dimensions mentally attributed the reference object and prepositions that situate the located object with respect to the physical dimensions of the reference object.

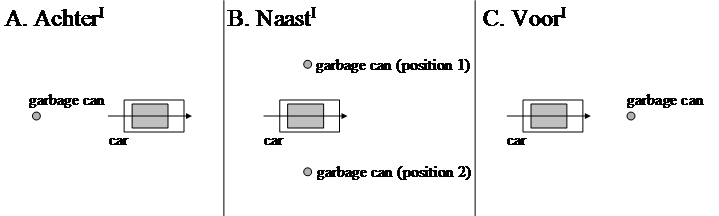

Section 1.3.1.2.1 has shown that the prepositions achter'behind', naast'next to' and voor'in front of' can be used both deictically and inherently. The inherent uses of these prepositions are illustrated again in Figure 18.

| a. | De vuilnisbak | staat | achter/naast/voor | de auto. | |

| the garbage.can | stands | behind/next.to/in.front.of | the car |

| b. | Jan zet | de vuilnisbak | achter/naast/voor | de auto. | |

| Jan puts | the garbage.can | behind/next.to/in.front.of | the car |

The computation of the location of the located object depends on what is considered the back or the front of the reference object. It should be noted that this depends largely on convention in the sense that the dimensional properties of the reference object do not play a role. Some examples: the front of a car is determined by the direction the car normally goes, the front of a building is generally determined by its main entrance, and the front of a TV set is determined by the placement of the screen. Other factors may play also a role, as will be clear from comparing the examples in (217).

| a. | Jan zit | voor | de televisie. | |

| Jan sits | in.front.of | the TV.set | ||

| 'Jan is watching television.' | ||||

| b. | Jan zit | achter | zijn computer. | |

| Jan sits | behind | his computer | ||

| 'Jan is working on his computer.' | ||||

Although the examples in (217) imply that Jan is situated in similar positions with respect to the two screens, antonymous prepositions are used. The reason for this is that achter is also used to indicate that Jan is operating the reference object. This will be clear from the following examples.

| a. | Jan zit | achter | het stuur. | |

| Jan sits | behind | the steering wheel | ||

| 'Jan is driving the car.' | ||||

| b. | Jan zit | achter | de piano. | |

| Jan sits | behind | the piano | ||

| 'Jan is playing the piano.' | ||||

| c. | Jan zit | achter de knoppen. | |

| Jan sits | behind the buttons | ||

| 'Jan controls everything.' | |||

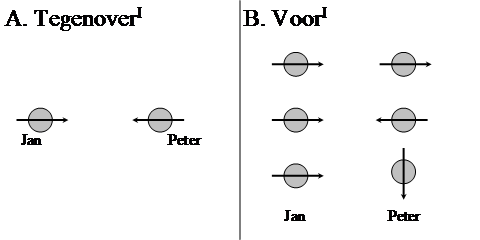

Another preposition that belongs to this group of inherent prepositions is tegenover'opposite'. It differs from the prepositions achter, naast and voor in that it refers not only to the orientation of the reference object but also that of the located object; it expresses that the located object faces the front of the reference object. This can be made clear by means of example (219a). This example refers to the situation in Figure 19A, in which Jan and Peter are facing each other. Of course this situation can also be described by means of example (219b), but the difference between the two is that the orientation of the located object is not relevant in the case of voor; as is shown in Figure 19B, (219b) can be applied to a wider range of situations than (219a).

| a. | Peter staat | tegenover | Jan. | |

| Peter stands | opposite | Jan | ||

| 'Peter is standing opposite Jan.' | ||||

| b. | Peter staat | voor | Jan. | |

| Peter stands | in.front.of | Jan | ||

| 'Peter is standing in front of Jan.' | ||||

In connection with this difference between tegenover and voor, it can be noted that the relation expressed by the former is reflexive, whereas this does not hold for the relation expressed by the latter. This is clear from the fact that we may conclude from (220a) that (220a') holds as well, and vice versa; the difference between the two examples is mainly one of prominence. From (220b), on the other hand, we cannot conclude that (220b') holds.

| a. | Peter staat tegenover Jan. | ⇔ |

| a'. | Jan staat tegenover Peter. |

| b. | Peter staat voor Jan. | ⇎ |

| b'. | Jan staat voor Peter. |

It should be noted, however, that there are cases in which the conditions on the use of tegenover seem less stringent than in (219a). Example (221a), for example, seems acceptable, although a tree is normally not construed as an object with a front and a back. One may even use (221b) to refer to a situation in which the front of the car is not directed towards the church. We can perhaps conclude from these examples that only the orientation of the reference object is crucial, and assume that (219a) is a special case. We leave this for future research.

| a. | De oude kersenboom | staat | tegenover de kerk. | |

| the old cherry tree | stands | opposite the church |

| b. | Mijn auto | staat | tegenover de kerk. | |

| my car | stands | opposite the church |

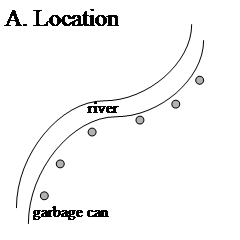

The discussion in the previous subsection has shown that the interpretation of achter, naast and voor is independent of the dimensional properties of the reference object. This does not hold for all prepositions. The preposition langs'along', for instance, is generally interpreted with respect to the length dimension of the reference object (note in this connection that langs is probably derived from the adjective lang'long'): in terms of vectors, we could say that langs denotes a set of vectors that are more or less parallel, that is, are all perpendicular to the exterior of the reference object. Like achter, naast and voor, the preposition langs can be used to denote either a location or a change of location (cf. (222)).

| a. | De vuilnisbakken | staan | langs de rivier. | |

| the garbage.cans | stand | along the river |

| b. | De bewoners | zetten | hun vuilnisbakken | langs de rivier. | |

| the residents | put | their garbage.cans | along the river |

Sometimes the importance of the length dimension of the reference object is weakened. Some examples illustrating this are given in (223). Further, it should be noted that the preposition langs can sometimes also be used directionally; cf. example (263 in Section 1.3.1.3, sub II).

| a. | Jan liep | even | langs | de slager. | |

| Jan walked | prt | along | the butcherʼs | ||

| 'John dropped in at the butcher's.' | |||||

| b. | Jan ging | even | langs oma. | |

| Jan went | prt | along grandma | ||

| 'Jan paid grandma a visit.' | ||||

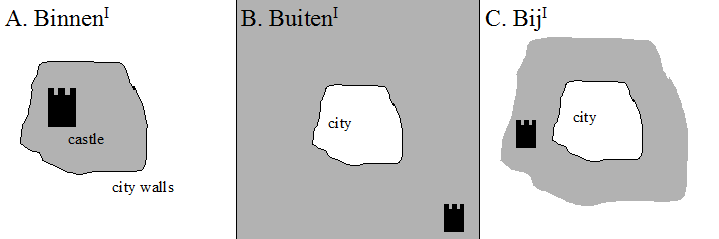

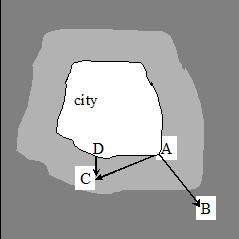

Other prepositions that depend on the dimensional properties of the reference object are binnen'inside/within', buiten'outside' and bij'near', which are referred to by Zwart (1997) as topological prepositions. They require that the reference object divide space into an interior and an exterior region. A PP headed by binnen indicates that the located object has a position in the interior region of the reference object, whereas a PP headed by buiten locates it in the exterior region. In this respect, bij is the same as buiten, but it has the additional requirement that the position be in the vicinity of the reference object (where the meaning of “being in the vicinity” is of course contextually determined). In Figure 21, the PPs in (224) denote a position within the grey area.

| a. | Het kasteel | staat | binnen | de stadswallen. | |

| the castle | stands | inside | the city walls | ||

| 'The castle is within the city walls.' | |||||

| b. | Het kasteel | staat | buiten | de stadswallen. | |

| the castle | stands | outside | the city walls | ||

| 'The castle is outside the city walls.' | |||||

| c. | Het kasteel | staat | bij | de stadswallen. | |

| the castle | stands | near | the city walls |

To conclude the discussion of this group of prepositions, it should be noted that it is not easy to work out the idea that these prepositions denote a set of vectors. In the first place, it is not clear what the starting point of the vectors is. Of course, we could make the idealization that the reference object is a point in space, which the vectors take as their starting point, but this would not help us in the case of binnen. Another possibility would be to assume that the positions in the relevant region are defined by means of the shortest vectors from the reference object to the positions in question; cf. Figure 22. This would solve the problem that, despite the fact that the magnitudes of the vectors  and

and  are identical, the location of position B but not position C can be properly described by means of (225a), and (b) can be used to describe position C but not position B. This is due to the fact that there is a shorter vector

are identical, the location of position B but not position C can be properly described by means of (225a), and (b) can be used to describe position C but not position B. This is due to the fact that there is a shorter vector  from the exterior of the reference object, which is not part of the denotation of ver buiten but of the denotation of vlak bij, so position C can be properly described by means of (225b).

from the exterior of the reference object, which is not part of the denotation of ver buiten but of the denotation of vlak bij, so position C can be properly described by means of (225b).

| a. | B/#C | ligt | ver | buiten | de stad. | |

| B/C | lies | far | outside | the city | ||

| 'B/C is far from the city.' | ||||||

| b. | C | ligt | vlak | bij | de stad. | |

| C | lies | close | near | the city | ||

| 'C is close to the city.' | ||||||

This solution to the problem does not, however, solve the problem that neither the direction nor the magnitude of the vectors denoted by binnen'inside' can be modified. For this reason, it has been assumed that binnen actually involves a null vector as well. Since we can offer no account for the facts that led to this assumption, we have to leave this problem for future research. See Subsection II for the difference between in/uit and binnen/buiten.

Prepositions that denote the null vector can be divided in two groups: prepositions that express that (part of) the located object is in the reference object, and prepositions that simply imply some contact between the located and reference objects.

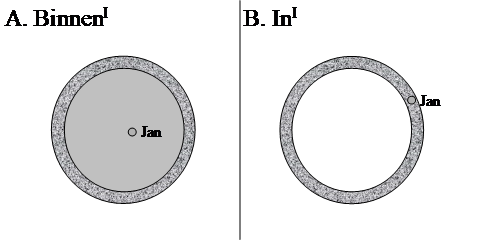

The prepositions in'in' differs from binnen'inside' in that it requires physical contact between the reference object and the located object, that is, in involves a null vector. This can be made clear for the examples in (226) by means of the pictures in Figure 23. The preposition binnen in (226a) does not imply any physical contact between Jan and the hedge; Jan must just be somewhere in the grey area in Figure 23A; the preposition in in (226b), on the other hand, does require physical contact, so that the situation must be as indicated in Figure 23B.

| a. | Jan zit | binnen | de haag. | |

| Jan sits | within | the hedge |

| b. | Jan zit | in | de haag. | |

| Jan sits | in | the hedge |

A caveat is in order, however. Example (226a) can be represented by making use of only two dimensions. When we are dealing with a three-dimensional object, on the other hand, the situation is slightly different. Given that it is the preposition in, and not binnen, that is used in the examples in (227), we conclude that the inside of a three-dimensional object is mentally construed as a part of the reference object rather than as its interior region.

| a. | De vogel | zit in/*binnen | de kooi. | |

| the bird | sits in/inside | the cage | ||

| 'The bird is in the cage.' | ||||

| b. | Jan is in/*binnen | zijn kamer. | |

| Jan is in/inside | his room | ||

| 'Jan is in his room.' | |||

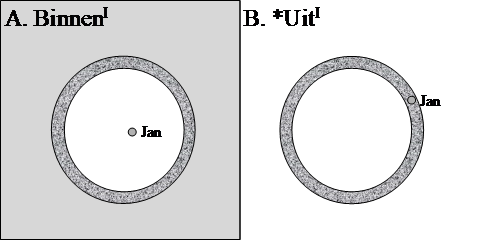

Like in but unlike buiten'outside', uit'out of' implies that there is some physical contact with the reference object. For this reason, buiten can, but uit cannot be used to refer to the situation depicted in Figure 24. Actually, uit cannot be used at all in (228b), since, when there is physical contact with the reference object, in will take precedence over uit; cf. Jan zit in de haag.

| a. | Jan zit | buiten | de haag. | |

| Jan sits | outside | the hedge |

| b. | * | Jan zit | uit | de haag. |

| Jan sits | out.of | the hedge |

Buiten also seems to be preferred in the case of three-dimensional objects. Occasionally, however, uit can be used as well. It is not clear to us under what conditions uit can or cannot be used with three-dimensional objects.

| a. | De vogel | zit | buiten/*uit | zijn kooi. | |

| the bird | sits | outside/out.of | his cage | ||

| 'The bird is outside its cage.' | |||||

| b. | De vogel | is | ?buiten/uit | zijn kooi. | |

| the bird | is | outside/out.of | his cage | ||

| 'The bird is out of its cage.' | |||||

| c. | De pen | ligt buiten/uit | zijn doos. | |

| the pencil | lies outside/out.of | his box | ||

| 'The pencil is out of its box.' | ||||

The discussion above shows that the preposition buiten is normally preferred to uit with stative verbs of location. Example (230b) shows, however, that the preposition uit is possible if we use a verb of change of location like halen'to get', whereas buiten is not allowed in this context. This is due to the fact that this verb expresses that the contact between the located and reference object is broken. For completeness' sake, we show in (230a) that the antonym of halen, stoppen'to put', licenses in only.

| a. | Jan stopt | de vogel | in/*binnen | de haag. | |

| Jan puts | the bird | in/inside | the hedge |

| b. | Jan haalt | de vogel | uit/*buiten | de haag. | |

| Jan gets | the bird | out.of/inside | the hedge |

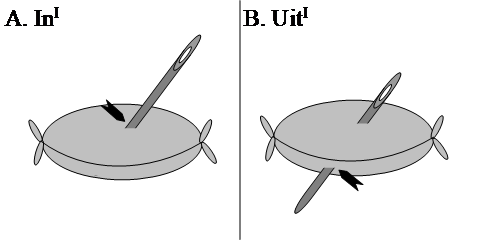

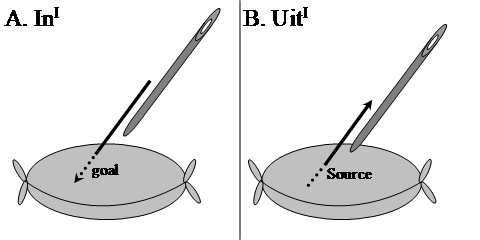

The prepositions in and uit imply physical contact between the located and reference object at some point in time. The preposition in does not imply, however, that the located object is fully physically enclosed by the reference object; this may only be partially the case. Similarly, the preposition uit implies that at least some part of the located object sticks out of the reference object. This can be made clear by means of the examples in (231); the arrows in Figure 25 indicate the points that are relevant for the interpretation of the examples in (231).

| a. | De naald | zit | in het speldenkussen. | |

| the needle | sits | in the pincushion | ||

| 'The needle sticks in the pincushion.' | ||||

| b. | De naald | steekt | uit | het speldenkussen. | |

| the needle | sticks | out.of | the pincushion | ||

| 'The needle sticks out of the pincushion.' | |||||

In and uit differ in that the former is compatible with full encompassment, whereas the latter necessarily implies partial encompassment. This is clear from the fact that the adverbial phrase helemaal'completely' can be used with in, but not with uit (unless we are dealing with an overstatement). Note that, as expected, substituting bijna helemaal'nearly completely' for helemaal in (231b) will give rise to a fully acceptable result. A modifier like een klein stukje'a small piece', which expresses that the encompassment is not complete, is possible with both PPs.

| a. | De naald | zit | helemaal/een klein stukje | in het speldenkussen. | |

| the needle | sits | completely/a small piece | in the pincushion | ||

| 'The needle sticks completely/partly in the pincushion.' | |||||

| b. | De naald | steekt | ??helemaal/een klein stukje | uit | het speldenkussen. | |

| the needle | sticks | completely/a small piece | out.of | the pincushion | ||

| 'The needle sticks completely/partly out of the pincushion.' | ||||||

The examples in (230) have already shown that the prepositions in and uit can also be used to denote a change of location; cf. Figure 26. Some more examples are given in (233): in (233a) the reference object refers to the new position of the located object, and in (233b) it refers to its original one. In this case, the adverbial phrase helemaal'completely' can be readily used with both PPs; helemaal in (233b) expresses that the contact between the located and the reference object is completely broken.

| a. | Jan steekt | de naald | (helemaal/een klein stukje) | in | het speldenkussen. | |

| Jan puts | the needle | completely/a small piece | into | the pincushion | ||

| 'Jan puts the needle (completely/partly) into the pincushion.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan haalt | de naald | (helemaal/een klein stukje) | uit | het speldenkussen. | |

| Jan gets | the needle | completely/a small piece | out.of | the pincushion | ||

| 'Jan gets the needle (completely/partly) out of the pincushion.' | ||||||

The preposition door in a sense combines the meanings of in and uit. In (234a), the PP door het speldenkussen expresses that the located object sticks both in and out of the reference object; in other words both points indicated by means of the arrows in Figure 27A are relevant. In (234b), the PP indicates that the located object ends up in the position in Figure 27A as the result of Janʼs action; this is shown in Figure 27B.

| a. | De naald | steekt | door | het speldenkussen. | |

| the needle | sticks | through | the pincushion |

| b. | Jan steekt | de naald | door | het speldenkussen. | |

| Jan sticks | the needle | through | the pincushion |

The prepositions in and uit, on the one hand, and door, on the other, seem to differ in that the former can only be used in constructions involving (change of) location, whereas the latter can also occur in directional constructions. This is clear from the examples in (219) involving the verb of traversing rijden'to drive'; cf. Section 1.1.2.2. Whereas the examples in (235a) are marginal at best, (235b) is fully acceptable. The primed examples show that the intended directional meanings can (also) be expressed by using the adpositions in question as postpositions.

| a. | ?? | De auto | is in/uit | de autowasserette | gereden. |

| the car | is into/out.of | the car wash | driven | ||

| 'The car has driven into/out of the car wash.' | |||||

| a'. | De auto is de autowasserette in/uit gereden. |

| b. | De auto | is door | de autowasserette | gereden. | |

| the car | is through | the car wash | driven | ||

| 'The car has driven through the car wash.' | |||||

| b'. | De auto is de autowasserette door gereden. |

There is, however, a slight meaning difference between (235b) and (235b'), although it is hard to pinpoint it. Perhaps another example can clarify it. When Jan is driving on an unfenced path which at a certain point ends at a meadow, and Jan drives right through the meadow to a path on the other side of it, one would use the preposition rather than the postposition door, as is shown in the (a)-examples in (236). The contrast becomes even clearer if the reference object is an entity with a relatively small size, like a puddle of rainwater. However, if the unfenced path enters a wood, and Jan drives right through it, one can also use the postposition, as is shown in (236b'). This may suggest that in order to use door as a postposition the located object must be completely encompassed by the reference object, whereas this need not be the case if it is used as a preposition. We leave this to future research.

| a. | Jan is door het weiland/de regenplas | gereden. | |

| Jan is through the meadow/puddle | driven | ||

| 'Jan has driven through the meadow/puddle.' | |||

| a'. | # | Jan is het weiland/de regenplas door gereden. |

| b. | Jan is door het bos | gereden. | |

| Jan is through the wood | driven | ||

| 'Jan has driven through the woods.' | |||

| b'. | Jan is het bos door gereden. |

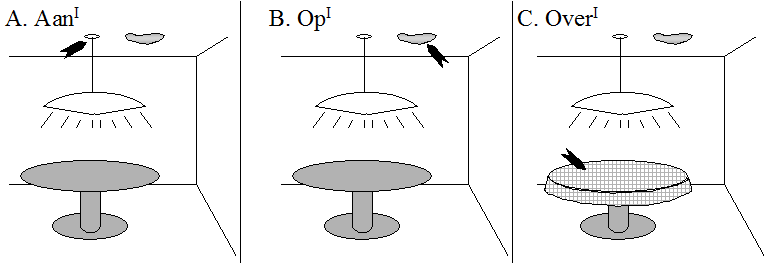

Whereas in, uit and door imply that the located object is at least partly located in the reference object, the prepositions aan, op, over and tegen in (237) merely require that there be some contact between the two.

| a. | Er | hangt | een lamp | aan het plafond. | |

| there | hangs | a painting | on the ceiling |

| b. | Er | zit | een vlek | op het plafond. | |

| there | is | a stain | on the ceiling |

| c. | Er | ligt | een kleed | over de tafel. | |

| there | lies | a cloth | over the table |

| d. | Er | staat | een ladder | tegen de muur. | |

| there | stands | a ladder | against the wall |

The four prepositions differ with respect to the nature of the contact that is implied. The preposition aan is compatible with minimal contact: the lamp in (237a) can be connected to the ceiling by means of its wire only. The preposition op suggests more extensive contact between the located and the reference object; the stain in (237b), of course, has maximal contact with the ceiling. The preposition over also suggests more extensive contact, but now it is the reference object that must have more extensive contact with the located object.

Note that it has also been claimed that the preposition aan expresses minimal distance, not minimal contact. Examples that would favor this are given in (238): these examples do not imply physical contact between the ship and the quay, or the house and the lake. If this is the proper characterization then aan must be assumed to denote a set of vectors which are smaller than a certain contextually determined magnitude, just like bij'near' shown in (224); aan and bij differ, however, in that only the former is compatible with physical contact.

| a. | Het schip | ligt | aan de kade. | |

| the ship | lies | on the quay | ||

| 'The ship is tied up to the quay.' | ||||

| b. | Het huis | staat | aan het meer. | |

| the house | stands | on the lake | ||

| 'The house stands near the lake.' | ||||

The examples in (237b&c) perhaps suggest that op and over imply some notion of full contact. That this is not the case will be clear from the examples in (239); example (239a) suggests that only the bottom of the lamp is in contact with the table (cf. Figure 7A), and (239b) is compatible with a situation in which the chair is only partially covered by the coat.

| a. | De lamp | staat | op de tafel. | |

| the lamp | stands | on the table |

| b. | De jas | hangt | over de stoel. | |

| the coat | hangs | over the chair |

In (237a-c) the PPs headed by aan, op and over refer to a location. The examples in (240) show that these PPs can also be used to indicate a change of location.

| a. | Jan hangt | een lamp | aan het plafond. | |

| Jan hangs | a painting | on the ceiling |

| b. | Jan zet | een lamp | op de tafel. | |

| Jan puts | a lamp | on the table |

| c. | Jan legt | een kleed | over de tafel. | |

| Jan puts | a cloth | over the table |

Note that op in (240b) necessarily means “on top of”. This is, however, not the case in the examples in (241). The verb brengen'to bring' in (241a) can be considered a movement verb and the verb maken in (241b) functions as a verb of creation.

| a. | Jan brengt | de verf | op het doek. | |

| Jan puts | the paint | on the canvas |

| b. | Jan maakte | een vlek | op het plafond. | |

| Jan made | a stain | on the ceiling |

The preposition tegen'against' is more difficult to characterize. It is often used in the sense of “touching the side surface of the reference object”, as in (237d), but resultative constructions such as (242) are possible as well.

| a. | Jan gooide | een pannenkoek | tegen het plafond. | |

| Jan threw | a pancake | against the ceiling |

| b. | Jan sloeg | Peter tegen de grond. | |

| Jan hit | Peter against the floor |

These examples suggest that tegen means (or may also mean) something like “touching the reference object while exerting force on it”, which would fit in nicely with the non-locational uses of tegen in examples such as (243).

| a. | Jan zwom | tegen | de stroom. | |

| Jan swam | against | the current |

| b. | Marie protesteerde | met kracht | tegen | dat besluit. | |

| Marie protested | with force | against | that decision |

| c. | Marie vocht | hard tegen | een ernstige griep. | |

| Marie fought | hard against | a serious flu |

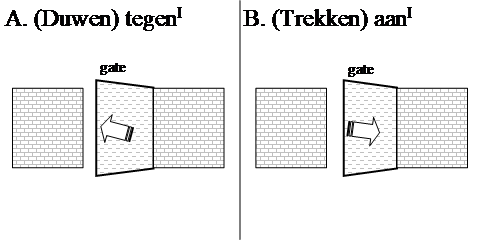

If the notion of exerting force is indeed appropriate in the characterization of the preposition tegen, it may be the case that tegen and aan act as antonyms with respect to the direction of the exerted force (in at least some cases). The examples in (244) may make this clear. The verbs duwen'to push' and trekken'to pull' both express that force is exerted on the complement of the (non-spatial) prepositional complement of the verb: in the first case the force is directed towards it, and only the preposition tegen can be used; in the latter case, on the other hand, the direction of the force is reversed, and only the preposition aan is possible. This is depicted in Figure 29, in which the arrow indicates the direction of the force exerted by Jan.

| a. | Jan | duwde | tegen/*aan | het hek. | |

| Jan | pushed | against/on | the gate |

| b. | Jan | trok | aan/*tegen | het hek. | |

| Jan | pulled | on/against | the gate |

- 1997Vectors as relative positions: a compositional semantics of modified PPsJournal of Semantics1457-86