- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

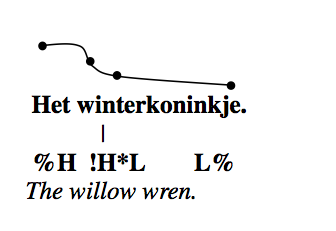

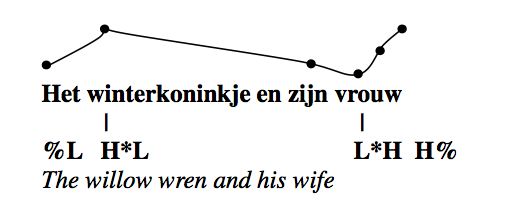

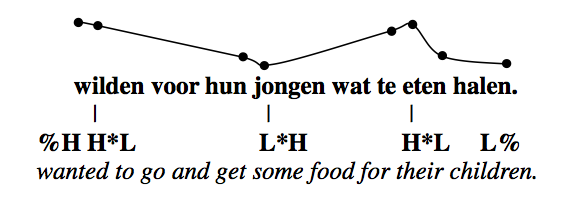

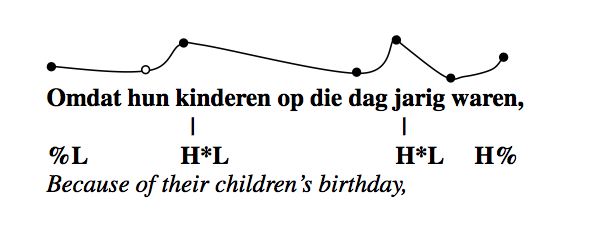

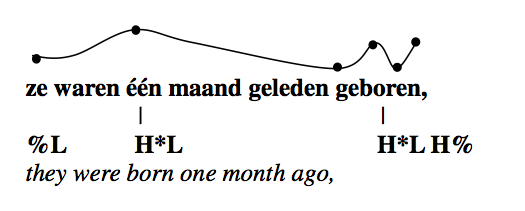

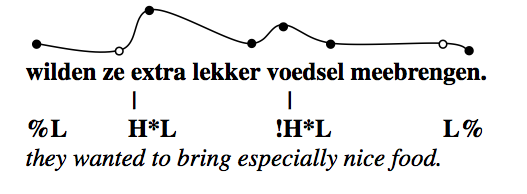

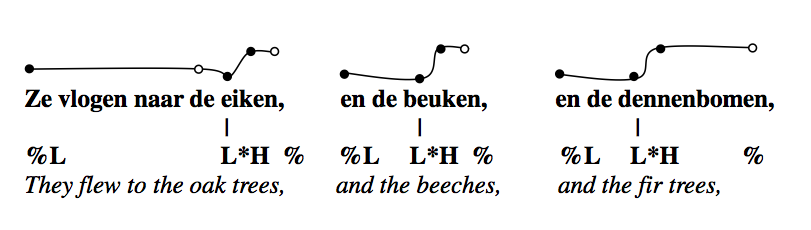

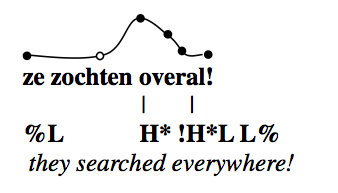

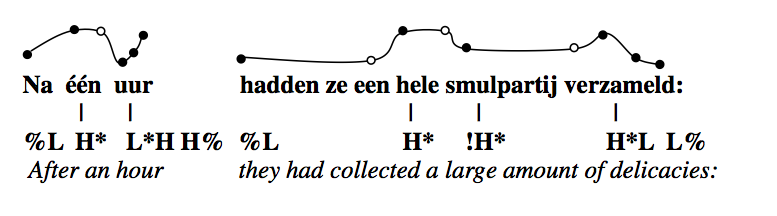

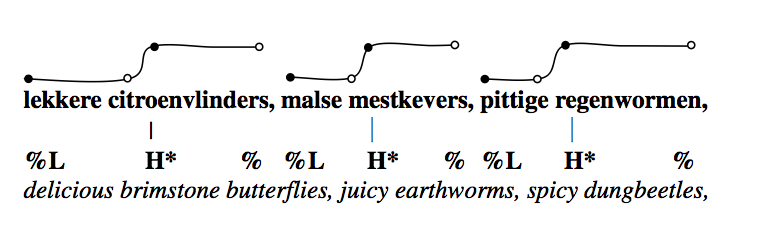

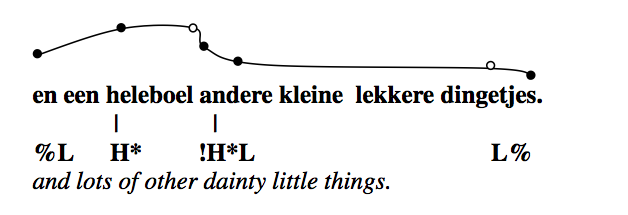

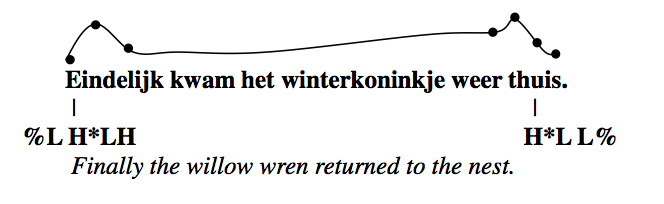

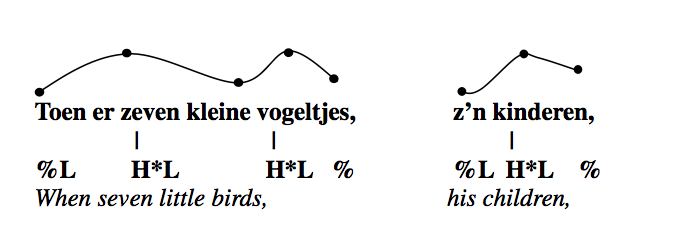

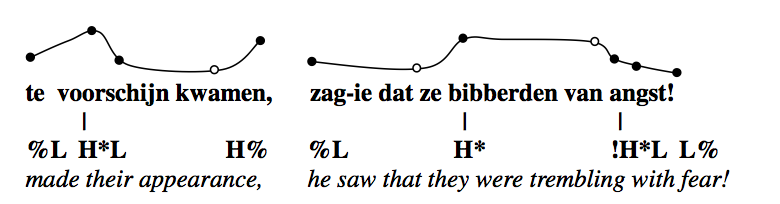

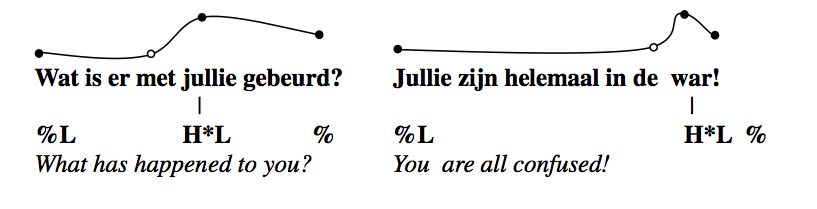

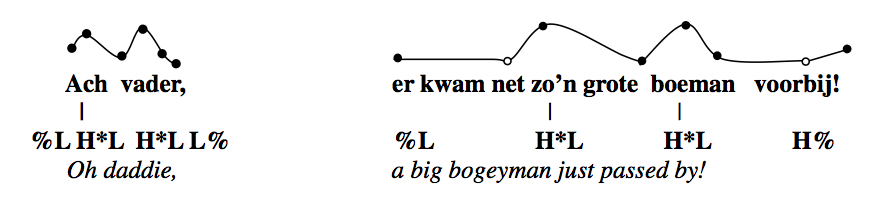

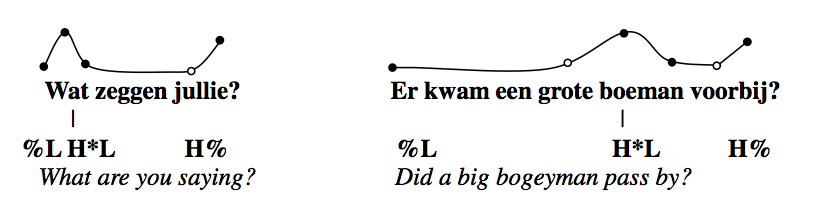

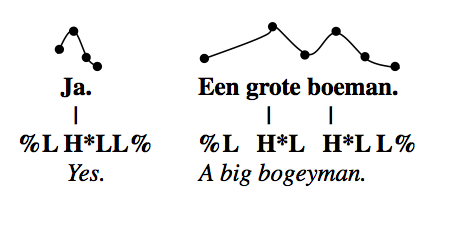

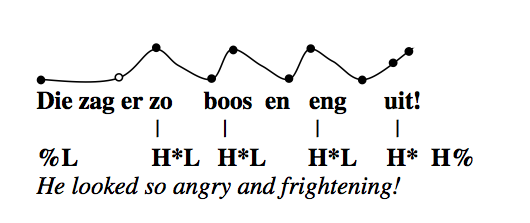

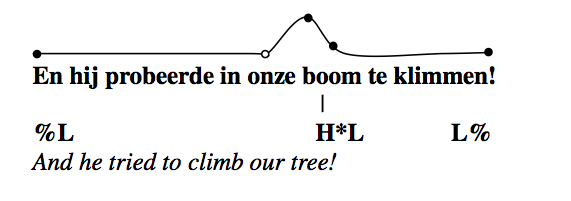

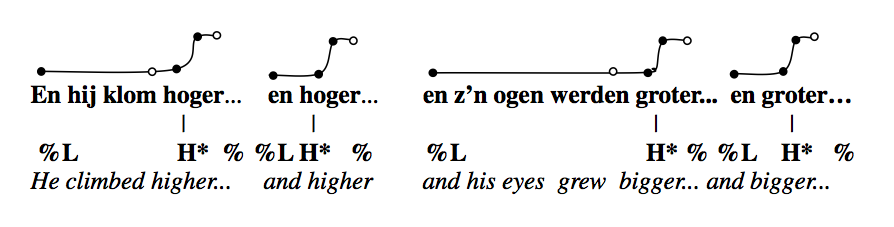

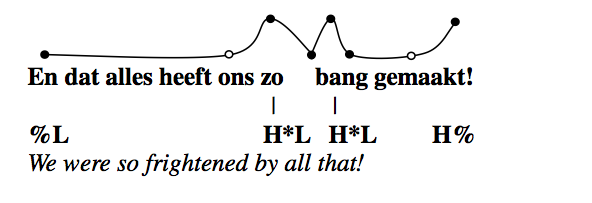

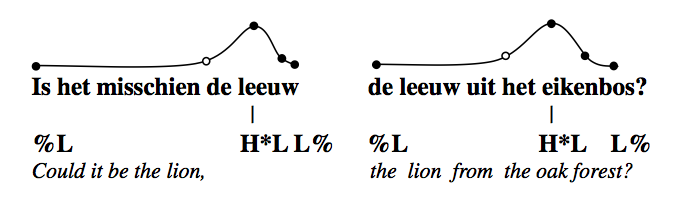

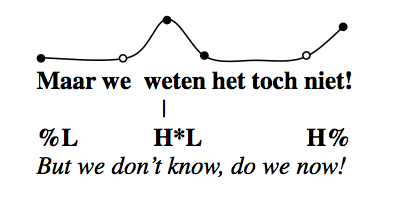

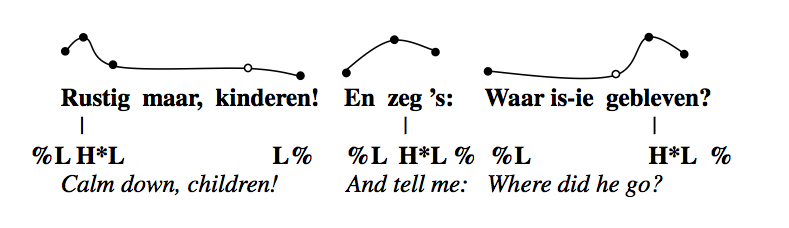

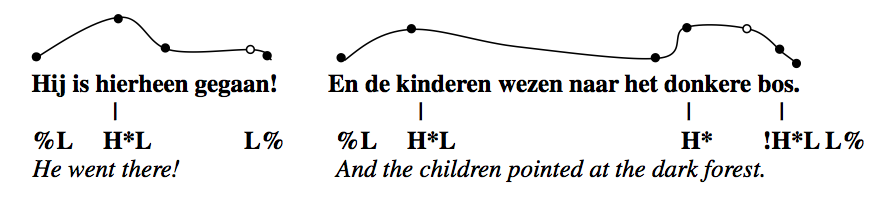

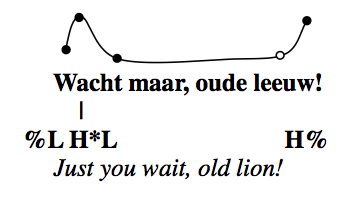

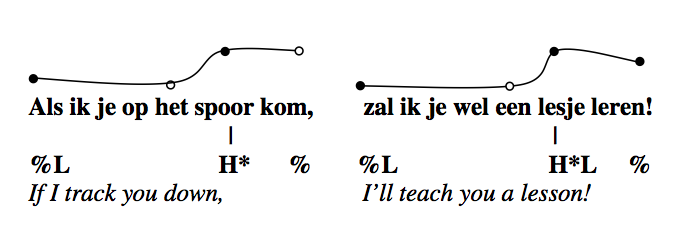

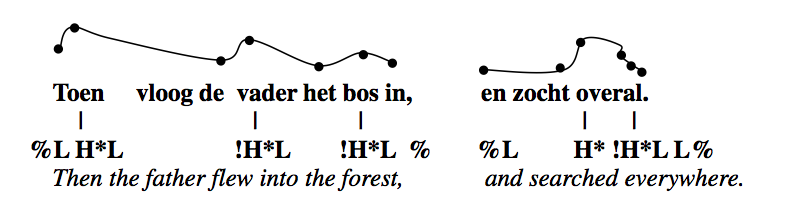

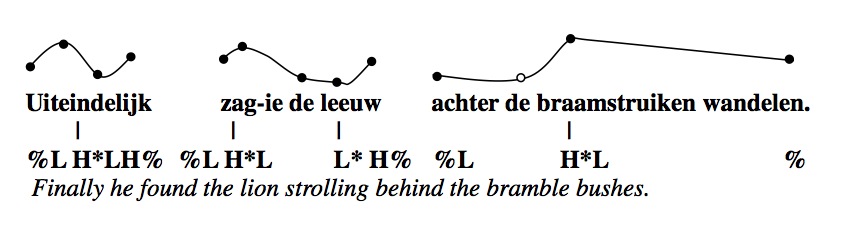

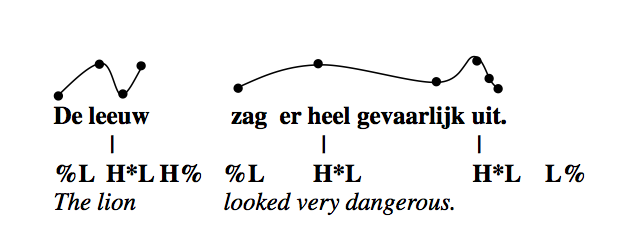

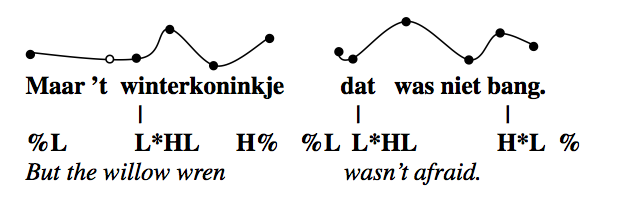

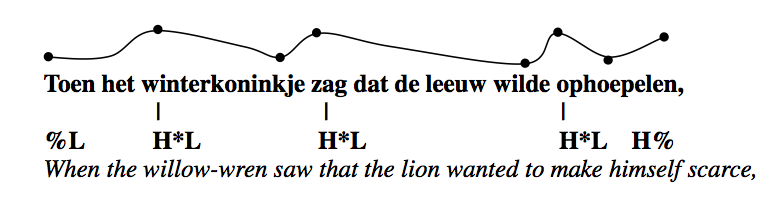

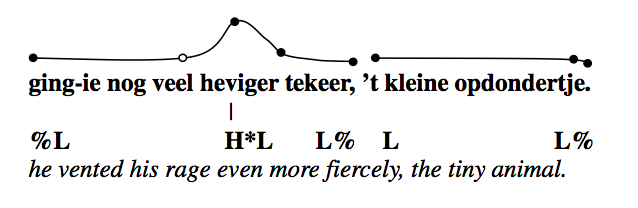

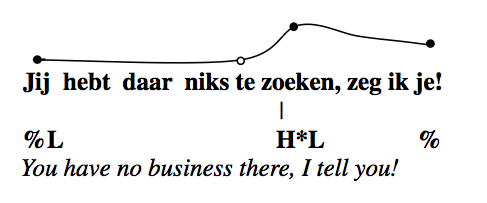

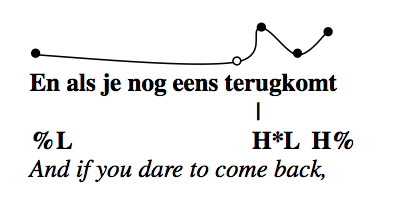

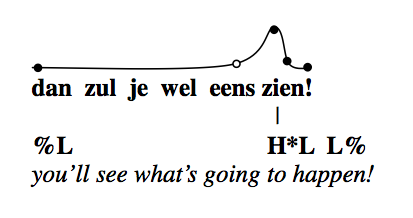

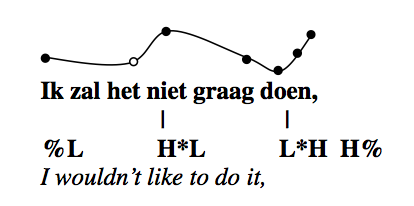

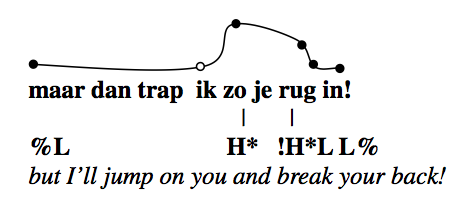

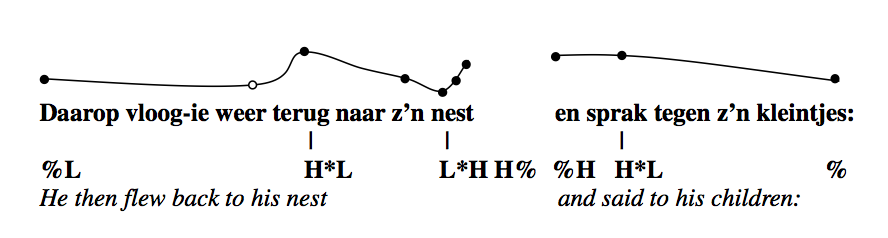

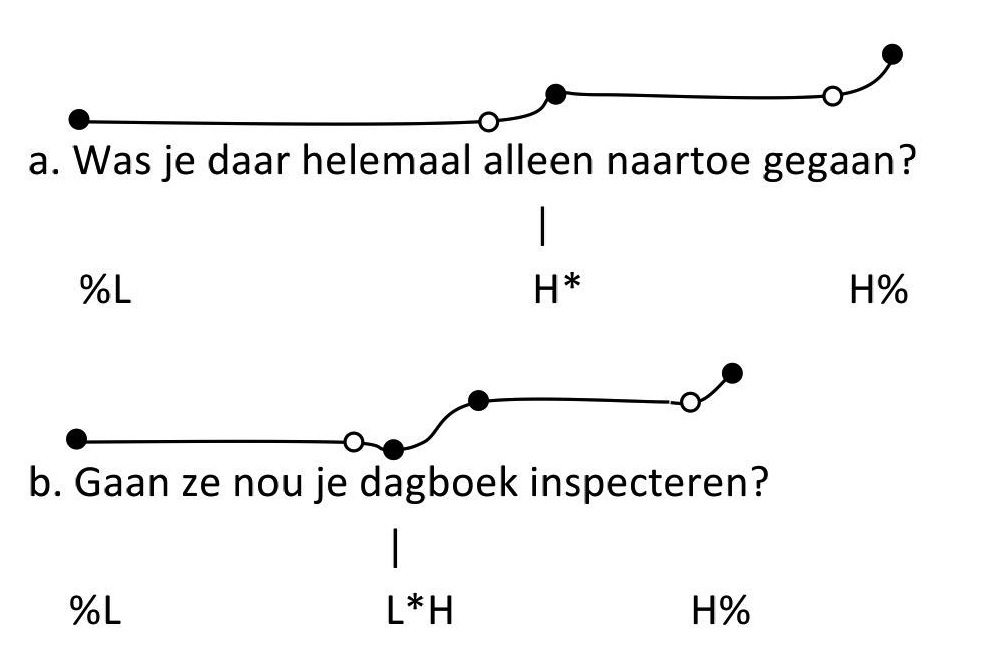

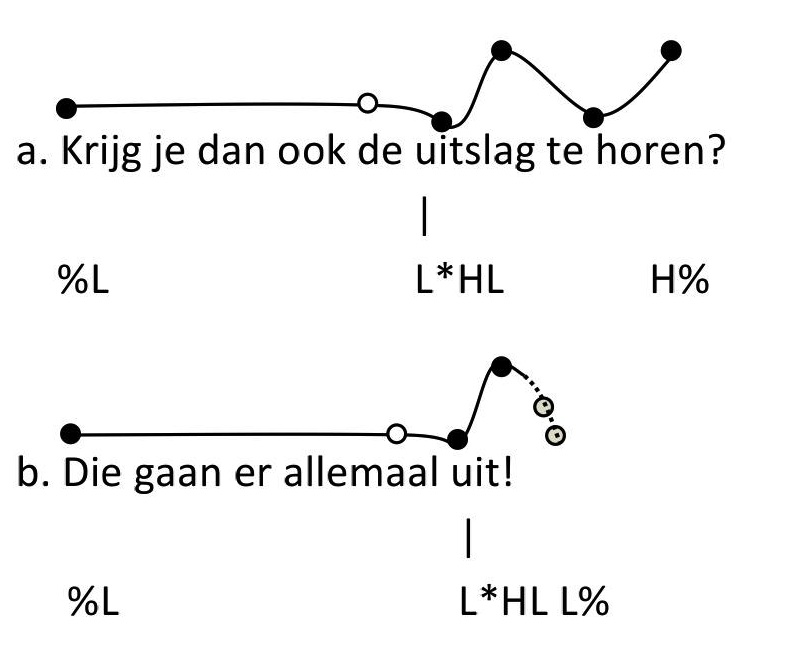

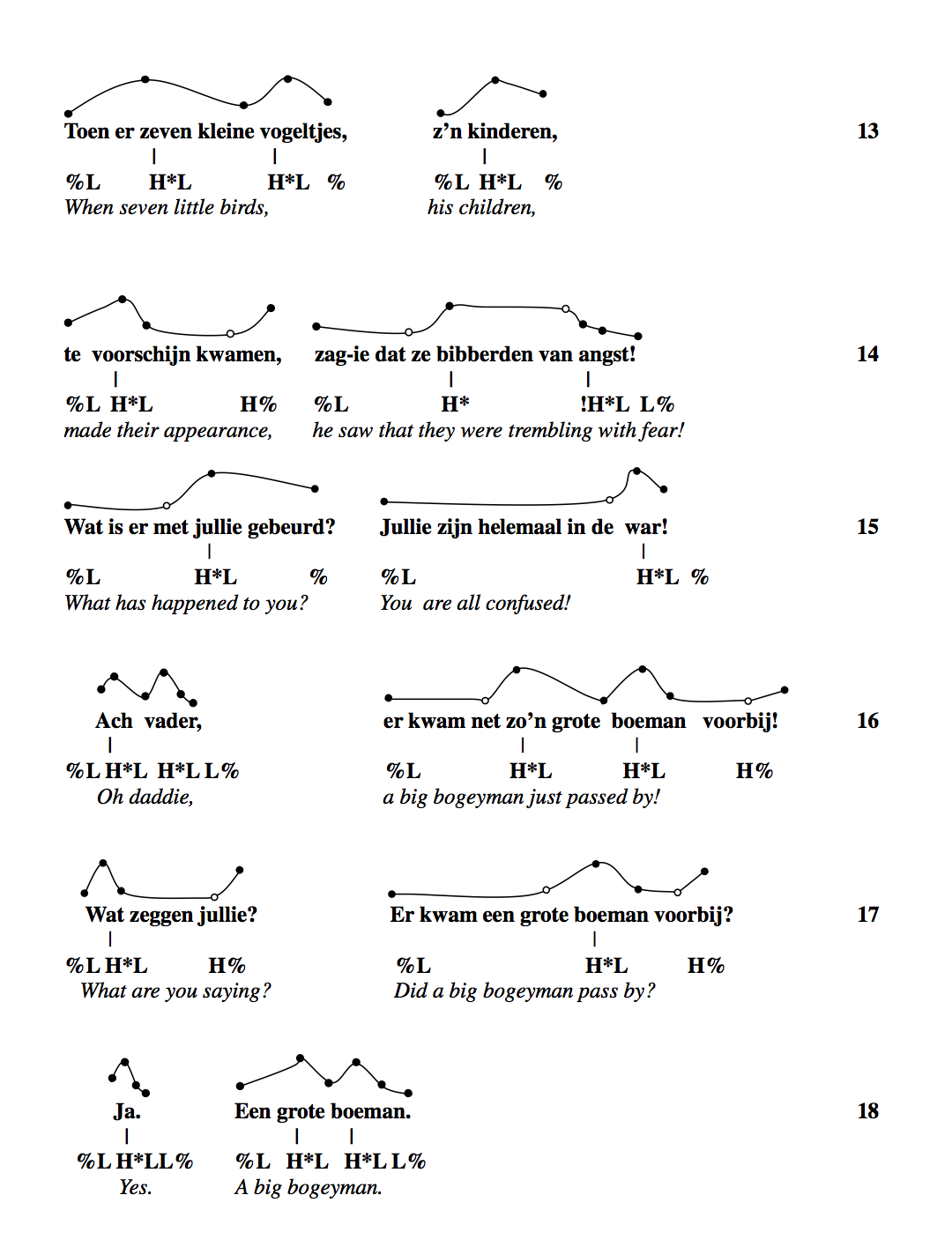

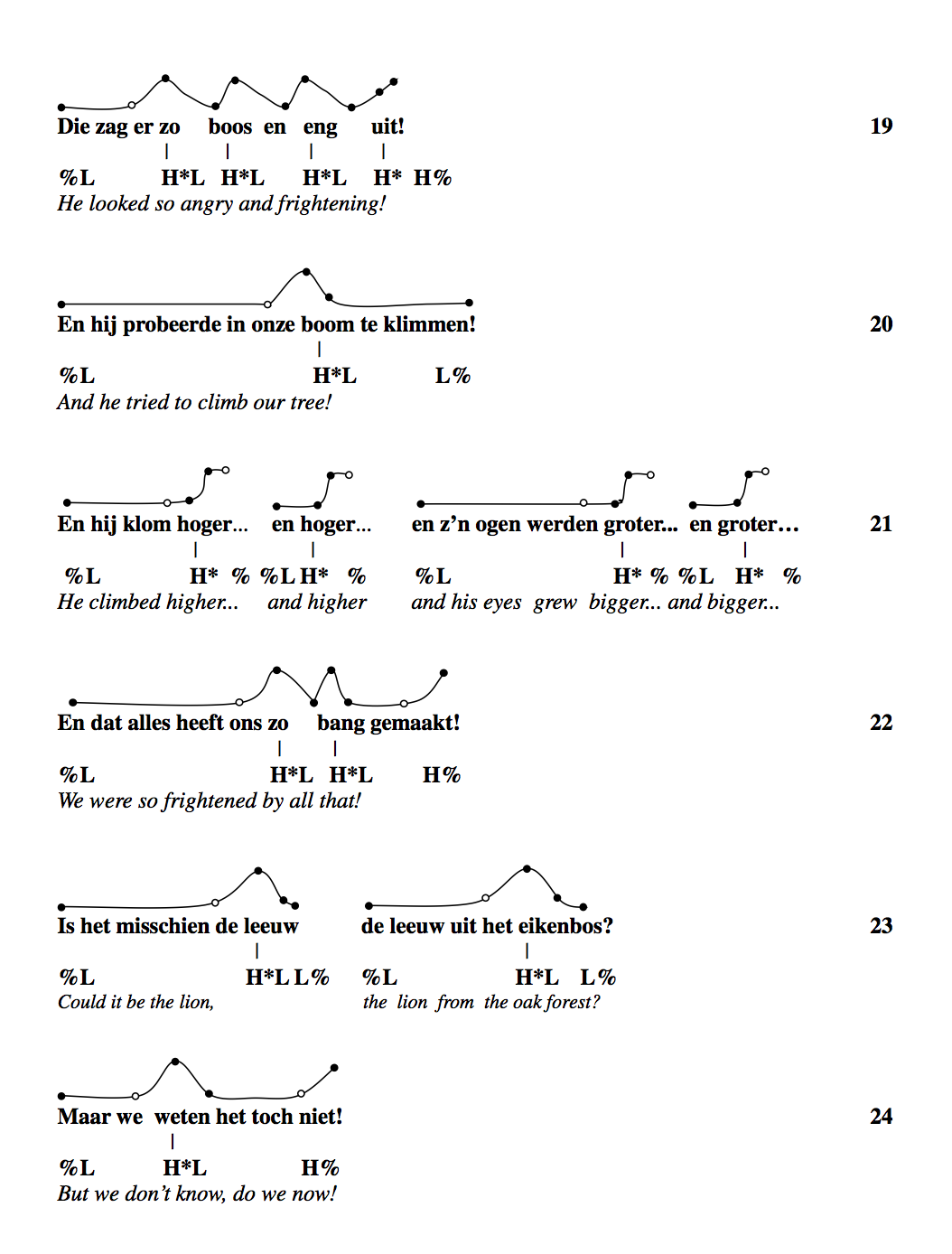

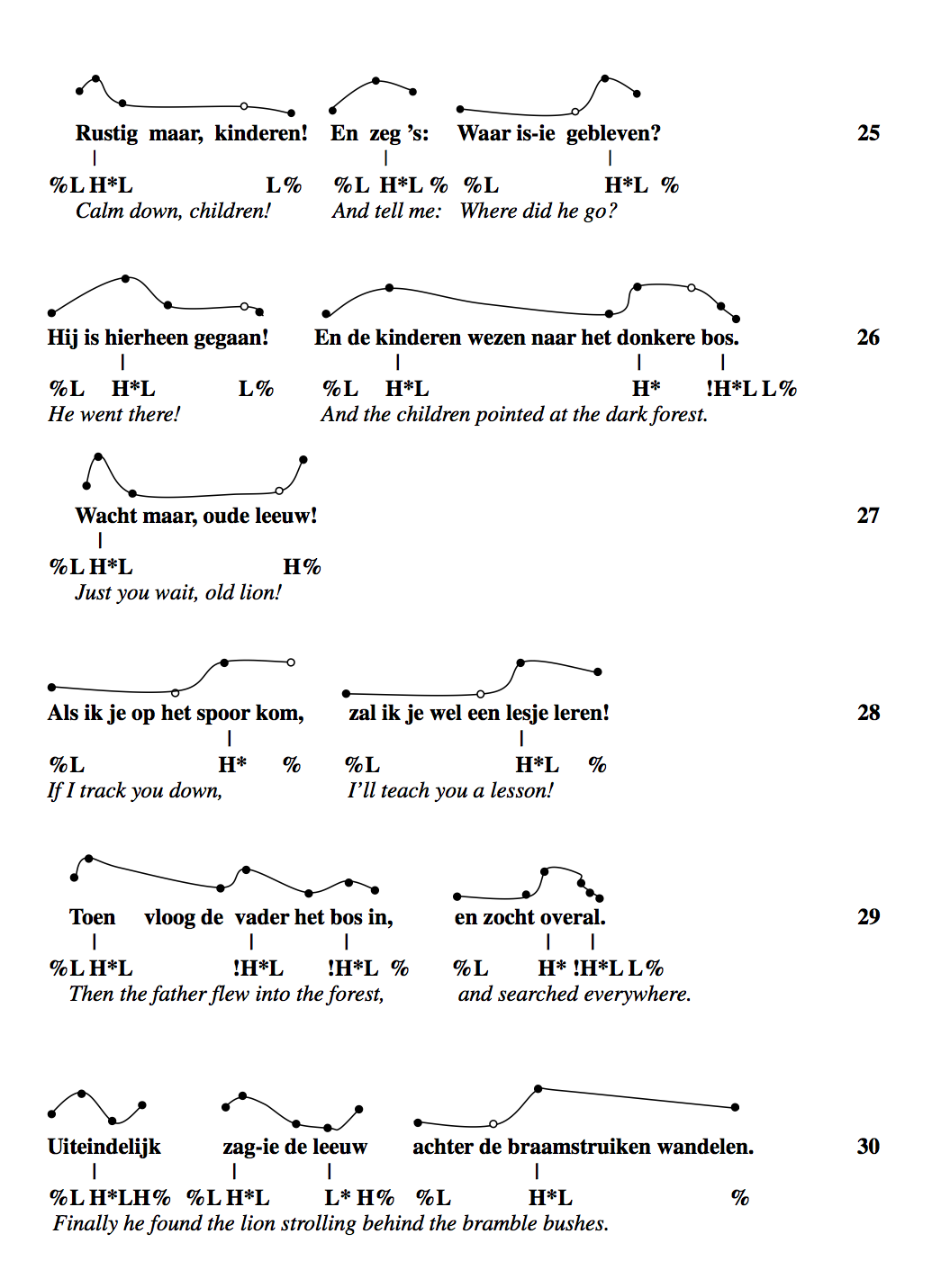

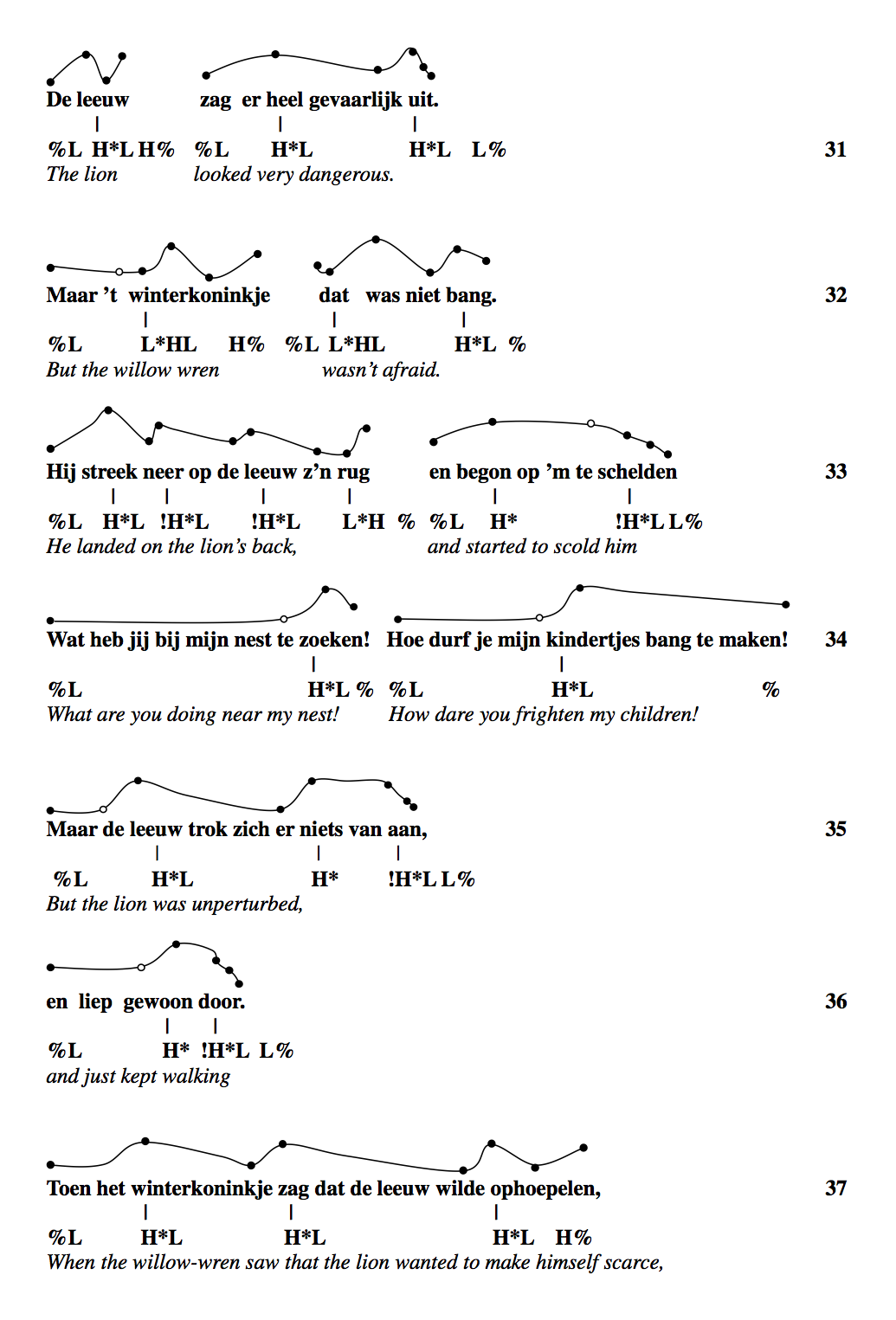

Dutch grammar has a repertoire of intonational patterns that can be described quite precisely, using boundary tones (%T, T%) and pitch accent tones (T*).

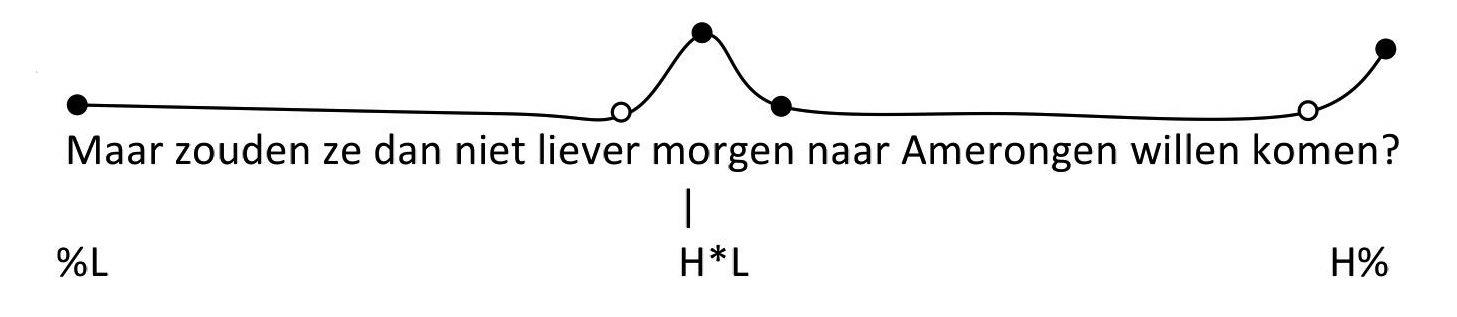

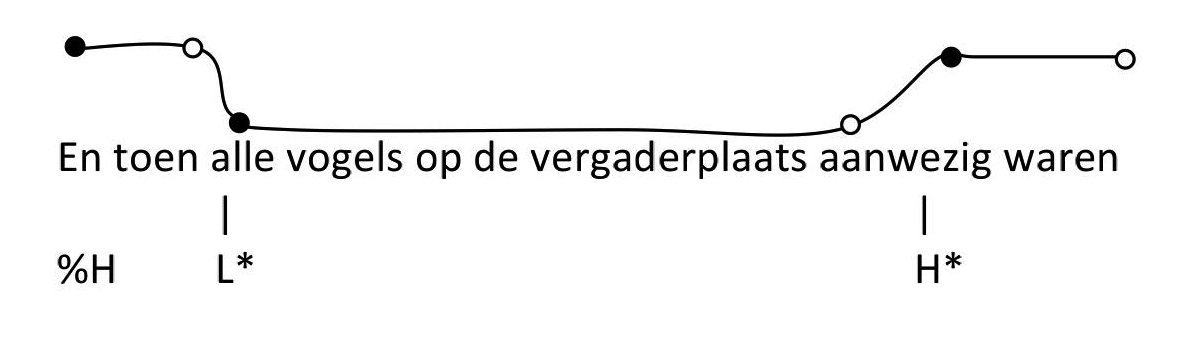

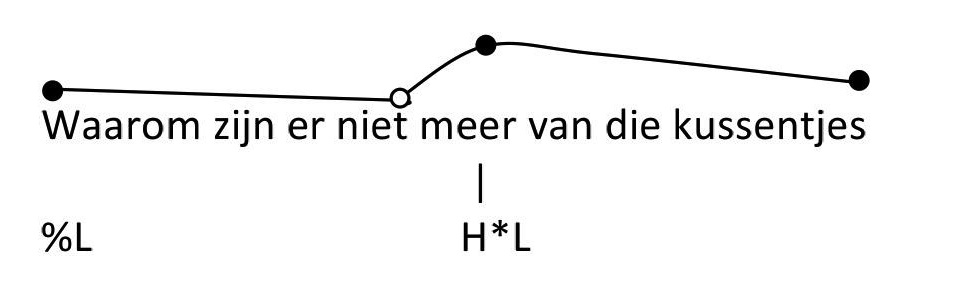

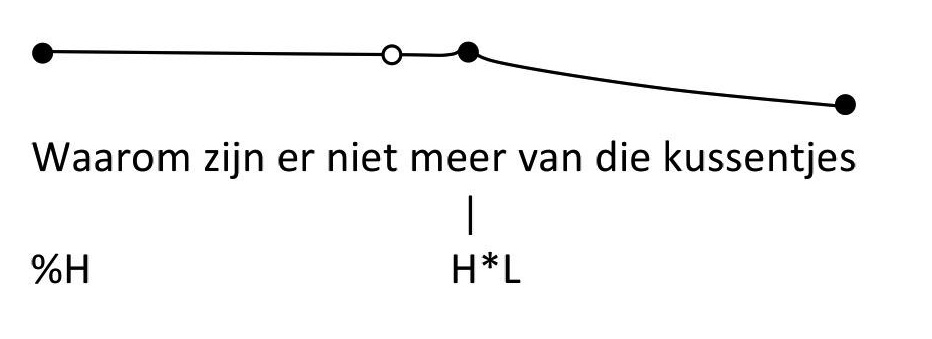

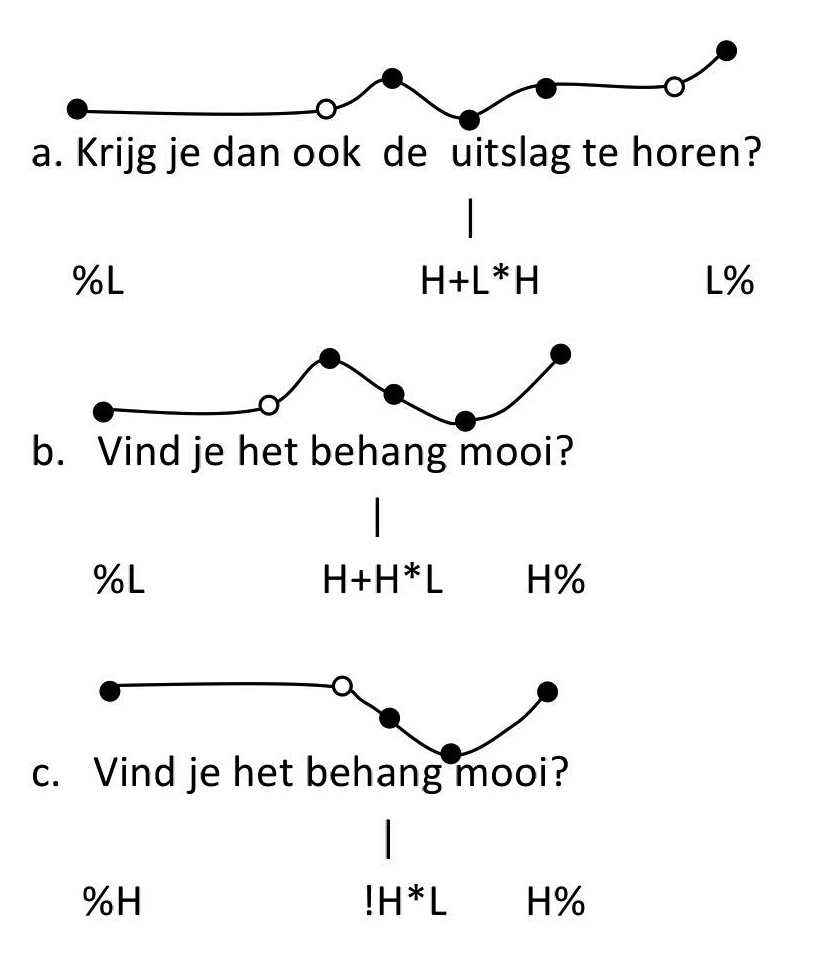

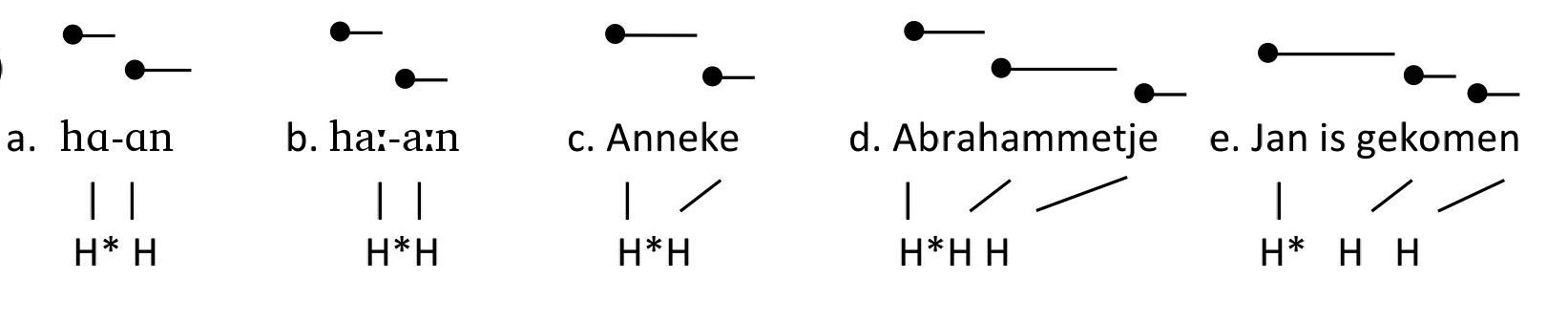

An autosegmental analysis consists of a string of low and high tones (L, H). Different kinds of tone can be distinguished on the basis of the place they take up in the larger phonological structure. Pitch accents are located in the accented syllables, of which every sentence or sentence fragment will have minimally one. The pitch accents of Dutch begin with a starred tone, and may have trailing tones after it. Thus, H* is a monotonal pitch accent, while H*L is a bitonal one. Boundary tones are located on the edges of the intonational phrase (IP). At the left edge, there must be either a %L or a %H, and at the right edge there may be either an L% or an H%. Since the final boundary tone is optional, there are three options at the right edge of the IP. A description will therefore include three elements. First, how is the utterance divided up into IPs; second, where are the pitch accents and, third, what tones are selected (cf. Halliday 1970).

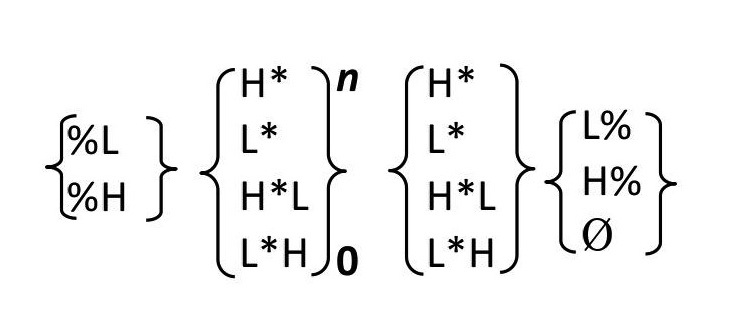

With the exception of the tone grammars of the Limburgisch and Rhenish dialects which have a lexical tone contrast (stoottoon vs sleeptoon, also Tonakzent/Accent 1 vs. Tonakzent/Accent 2) and which are for that reason tone languages, the tone grammars of the West Germanic languages have largely the same structure. In comparison with the tone grammars of other languages without lexical tone, the intonation of West Germanic languages is complex. We therefore introduce the grammar of Dutch in stages, beginning with a less complex tone grammar which covers the great majority of contours. This first stage is given in (1).

There are four positions in (1). The first is the left-edge boundary tone. The second the prenuclear accent, of which there can be any number, including zero, depending on the number of prenuclear accents in the sentence. The third is the nuclear pitch accent, the obligatory pitch accent of the sentence. The pitch accents in this position will at a later stage appear to be distinct from those in the prenuclear position. Finally, the fourth position is the right-edge boundary tone, which, as said above, is optional. As will be clear, the symbol 'Ø' stands for the absence of a right-edge boundary tone. For a sentence with two accents there will therefore be 2 x 4 x 4 x 3, or 96 contours.

The pronunciation of a tone is known as a target, which has a value on a vertical axis representing F0 and one on a horizontal time axis. The values of a tone's target on the two axes are determined by a large number of factors, like the language (Pierrehumbert's (1980) 'language-specific realization') and the phonological context (Pierrehumbert's (1980) 'context-sensitive realization'), quite apart from the variation due to style. The F0 contour arises through the way one target is connected up with an adjacent one.

The descriptions of British English intonation that were published in the twentieth century had a strong influence on the autosegmental analysis of Dutch. Because of this, the description of Dutch differs from the autosegmental analysis of American English presented by Pierrehumbert (1980), who did not build on the descriptions in the 'British tradition'. The way in which Pierrehumbert (1980) conceived of the phonological representation as distinct from its phonetic realization represented a breakthrough in the research on intonation. Its importance therefore lies not primarily in the details of her analysis of American English, but in the renewed conception of the relation between phonetics and phonology.

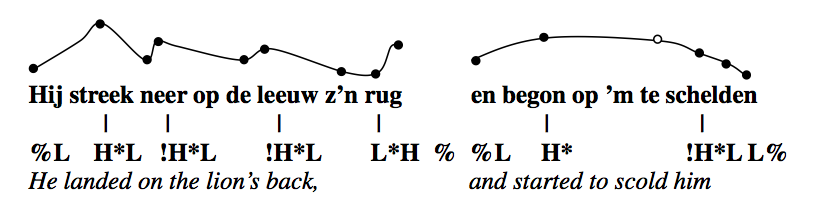

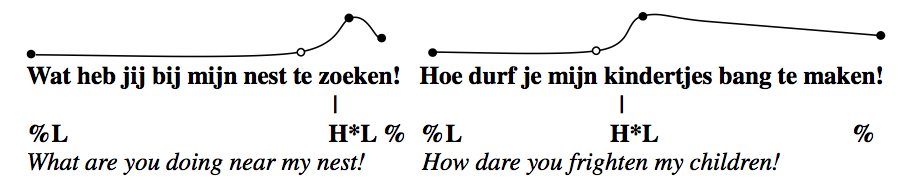

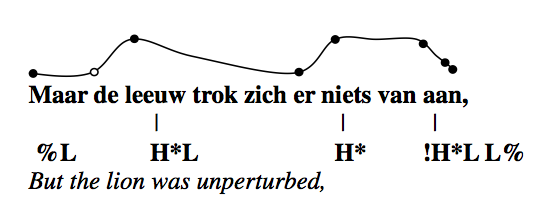

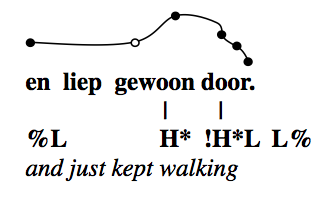

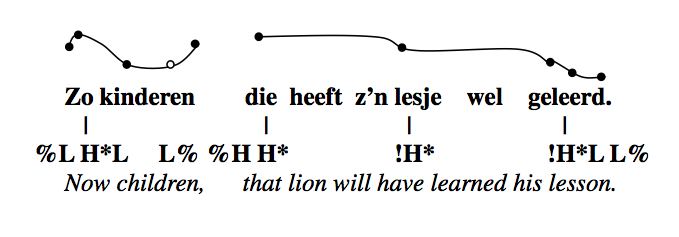

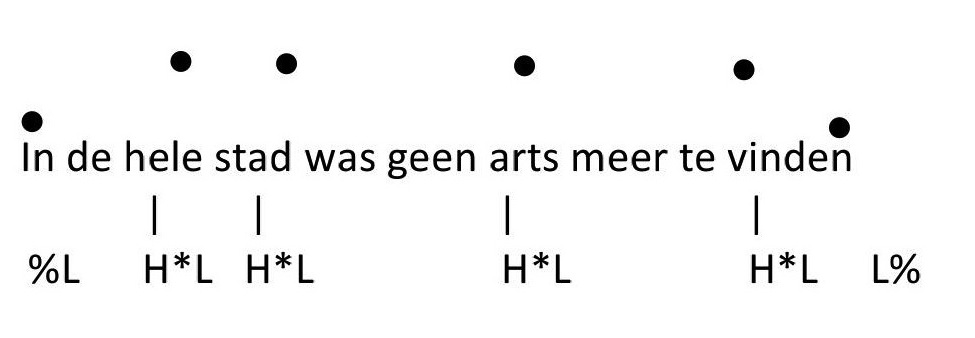

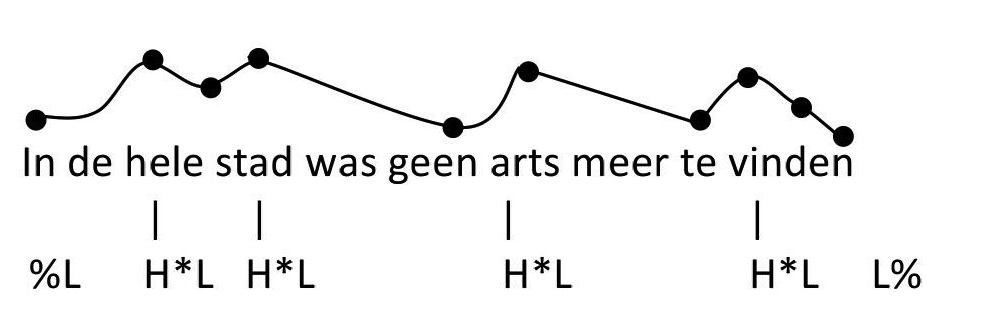

Contours that start with %L and have H*, L*, H*L or L*H for prenuclear and nuclear accents are among the most neutral contours of the language. Together with the three ways in which contours can end, L%, H% and Ø, they describe 48 two-accent contours, or 96 if the choice between %L and %H for the left boundary of the IP is included (see 1). Figure 2 consists of a single IP with four H*L pitch accents which ends in L%. The targets of tones are temporally aligned with three kinds of edges. These are the beginning of (the sonorant portion of) the rhyme of an accented syllable (for T*), the IP-boundary (for %T and T%) and the left edge of T* (for the trailing tone). In (2), the targets of the trailing tones have not yet been included. Of these three, the rhyme of the accented syllable is the only one that is given by the derivational history of the sentence, as it results from the way the accent rules of the language have provided words with accents. Each of the accented syllables must be associated with a starred tone (T*), as indicated with a vertical association line between the rime and T*. The boundary tones do not care about the syllabic structure, and are positioned (in the sonorant portions) on the edges of the IP.

A further example of such ‘double alignment’ is given in (5). The targets of the tones of monotonal pitch accents H* and L* continue up until the next tone specification in the IP or, if no further tones follow, till the end of the IP. The target (or targets, in the case of a longer stretch) of the prenuclear L* is usually somewhat lower than that of the preceding %L.

A final point concerns the realization of the L in a nuclear pitch accent when no right-edge boundary tone follows (see figure 6). The location of its target is at first sight unexpected, because it is rightmost rather than leftmost. On the basis of the description above, its mid-pitched (or not quite low pitched) target should be located close to that of H*, and be continued till the end of the IP. As it happens, that 'half-completed' falling contour is acoustically close to the vocative chant, so much so that a pronunciation with a mid-level pitch after H* would be interpreted as the vocative chant, a quite different intonation. To keep the half-completed fall distinct from the vocative chant, the gradually descening half-fall is used. There is therefore only one target for the trailing L in the context, as shown in (6).

There would appear to be a correlation between the choice of the left-edge %T and the first tone of the first pitch accent, T*, such that before L* a choice for %H is more probable (cf. 5), while before H* a choice for %L is preferred (cf. 6). A perception experiment tapping listeners’ intuition about the meaning of the two left-edge tones by Grabe et al. (1998) showed that speakers sound more engaged and friendly when %T and T* have opposite values, i.e. %L H* en %H L*. Their results suggest that (6) will sound friendlier than (7).

Summarizing, the trailing tone is pronounced rightmost in prenuclear pitch accents and leftmost in nuclear pitch accents, and linear interpolations are made between the tones of a pitch accent. Exceptionally, the trailing tone of nuclear H*L has its mid target rightmost whenever it occurs without a following T%. Between boundary tones and pitch accents, pitch is governed by the lefthand tone. We here conclude the illustration of the grammar in (1).

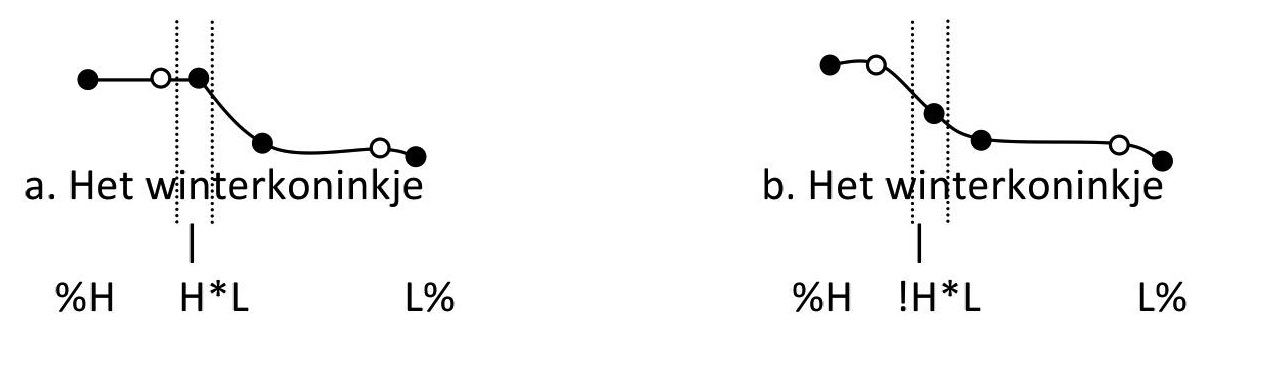

In this section, we expand the grammar in (1) in four ways. First, we discuss Downstep, a meaningful lowering of H* after H-tones. Next, we deal with a tritonal prenuclear pitch accent, and explain its position in the grammar as a restructuring of a two-phrase contour. Third, we introduce the leading H, which occurs on the syllable immediately before the accented syllable. L-Prefixation is the fourth addition to the grammar, which consists of a shifting of the pitch contour to the right in order to make room for an L-tone that functions as the starred tone of the pitch accent. This rule leads to more tritonal pitch accents. Finally, we introduce the vocative chant.

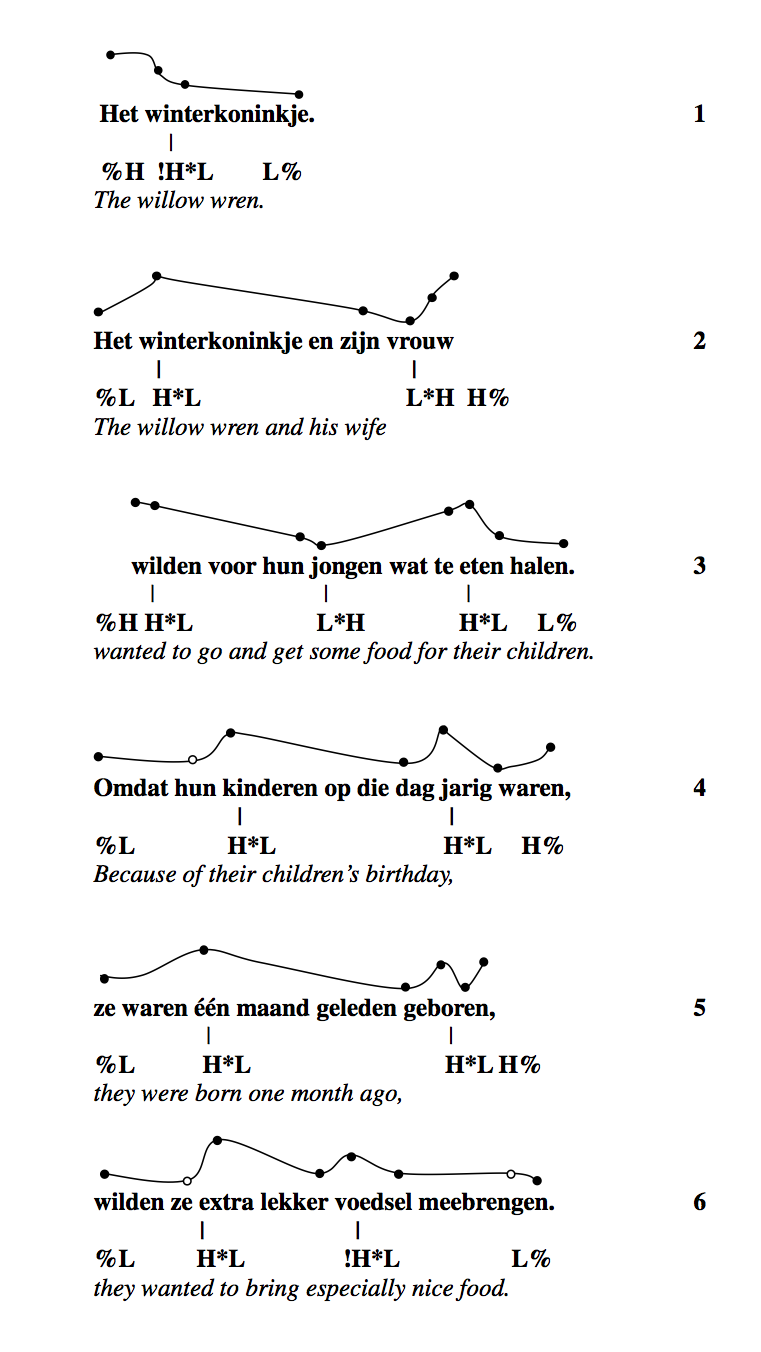

In (9a) and (9b) a minimal pair of het winterkoninkje the willow wren is presented. The difference in the vertical target of the two contours (the F0) leads to a horizontal (i.e. temporal) difference for the falling movement, which is later in (9b) than in (9a). In (9a) the start of the fall occurs towards the end of the sonorant rime [ɪn] in win-, while that in (9b) begins before the vowel. In these figures we have included the second target of L% in order to indicate that the difference between the accented syllables will be maintained if there are more unaccented syllables before the accented one.

The meaning of downstep is something like 'No contribution is now expected from the listener'. For this reason, it is a useful contour for the title of a story that is read to a class of school children. A child’s answer to 'Which story shall I read to you today?', asked by a teacher who is about to select a story from a book, might well be said as (9a), with no downstep, because the child expects a resolution of his suggestion. But (9b) would be the better option once the teacher started telling the story. The effect is something like 'And now the story begins!'

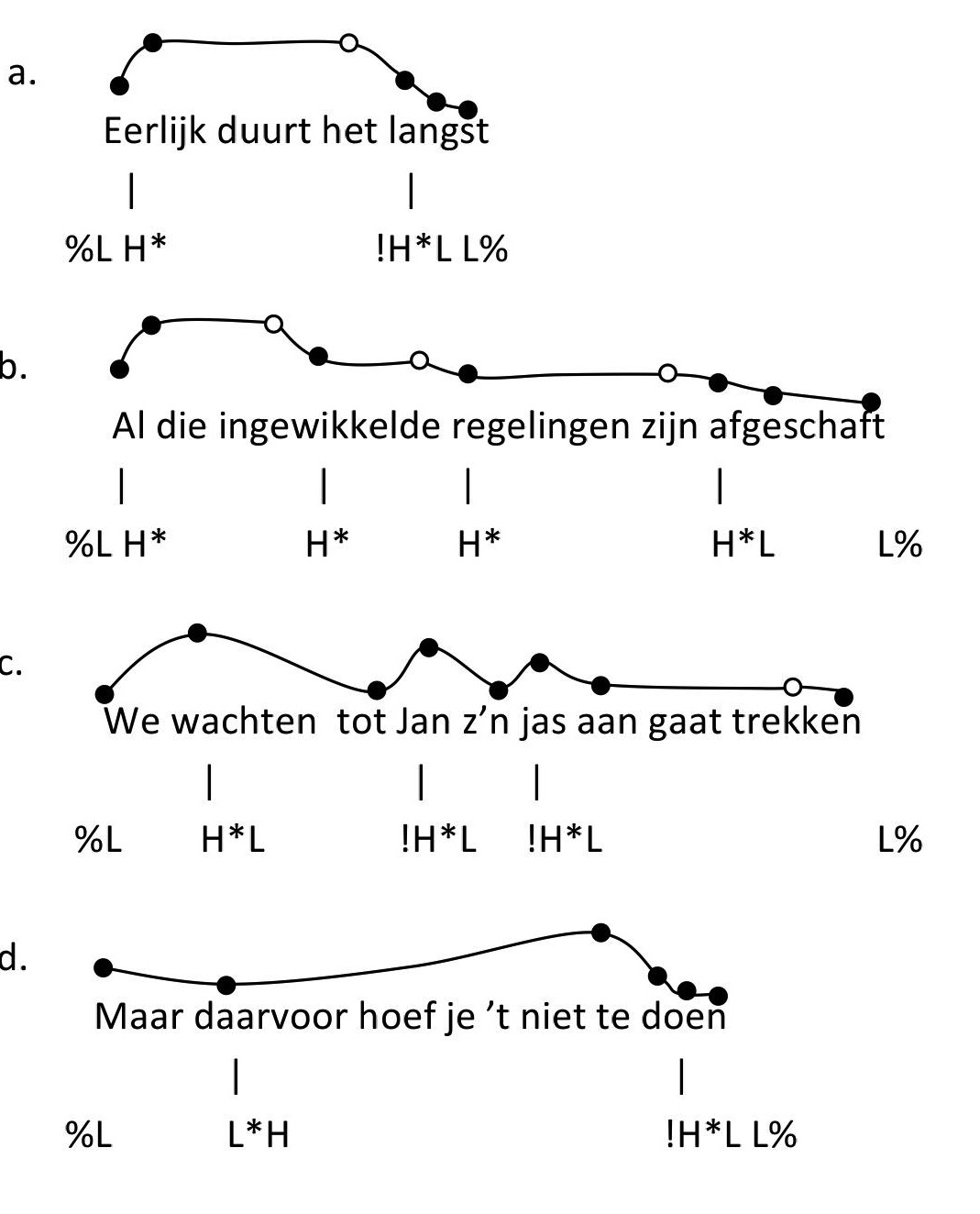

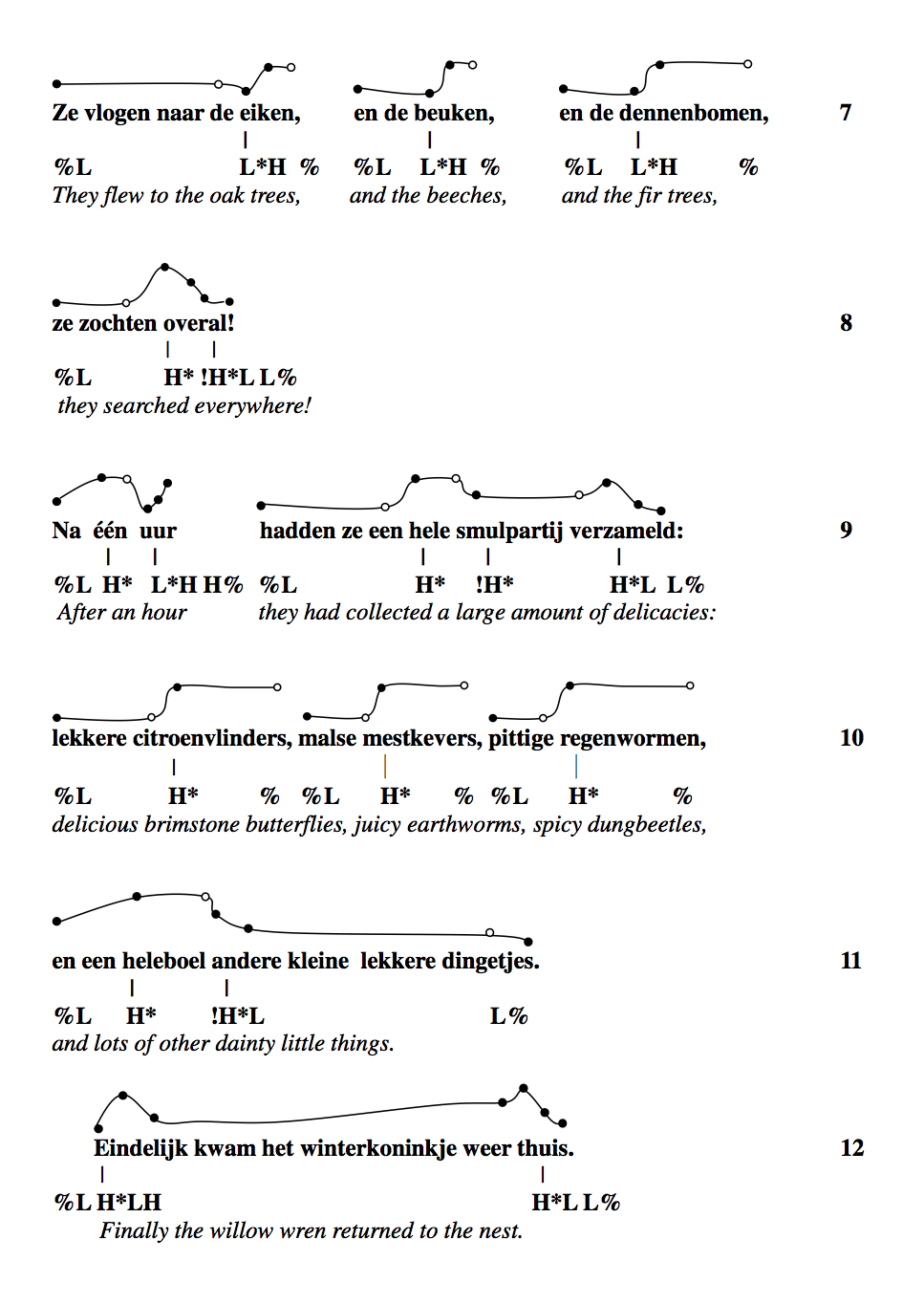

A well-known contour with downstep is one that became known as the flat hat (also known as the platte hoed). It is illustrated in (10a)Eerlijk duurt het langst Honesty is the best policy, which was described in Hart et al. (1990) as a contour consisting of an accent-lending rise followed by an accent-lending fall. In (10a), the context for !H* is the preceding H*. The non-downstepped variant of (10a), which is not given here, has a later fall, just like the fall in (9b). Figure 10b - Al die ingewikkelde regelingen zijn afgeschaft All those complicated regulations have been abolished - shows that downstep is iterative. That is, the target of every H* is lower than the one before. As a result, the H* pitch accents form a contour resembling the terracing of sloping terrains used for agriculture. Instead of H*, (10c) - We wachten tot Jan z'n jas aan gaat trekken We will wait till Jan will put his coat on - has H*L’s in pre-nuclear positon. The pronunciation of the trailing L-tones is observed as dips before the targets of H*, here on tot till en z'n his. Contour (10d) - Maar daarvoor hoef je 't niet te doen You don't need to do it for that - shows that the trailing H can provide the context for downstep. The target of H* is lowered, occurring after the end of the slow rise towards a point just before the accented syllable, on te.

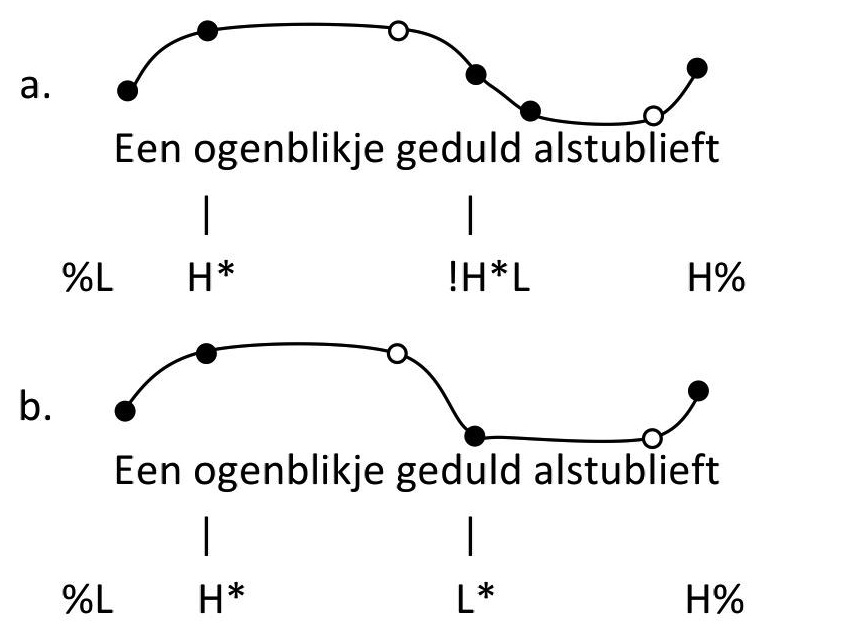

An interesting contrast is shown in (11a, b)een ogenblikje geduld alstublieft one moment please, where the downstepped H* before H% in (11a) contrasts with L* in (11b). Bruce Hayes was the first to notice that the description in Pierrehumbert (1980) did not account for the contrast between !H* and L*. In her description, a downstepped !H* was analyzed as H+L*. A realization rule treated L* as if it was !H*. Later analyses have generally replaced H+L* by H+!H* (Grice 1995: fn 7). Figure 11a is a request, but (11b) is an echo question. Their meanings are obviously different.

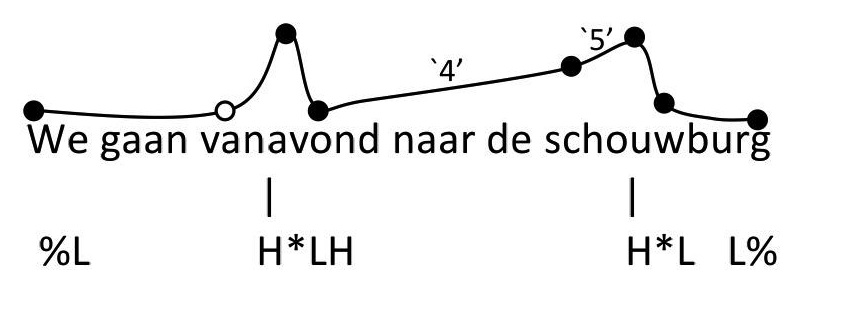

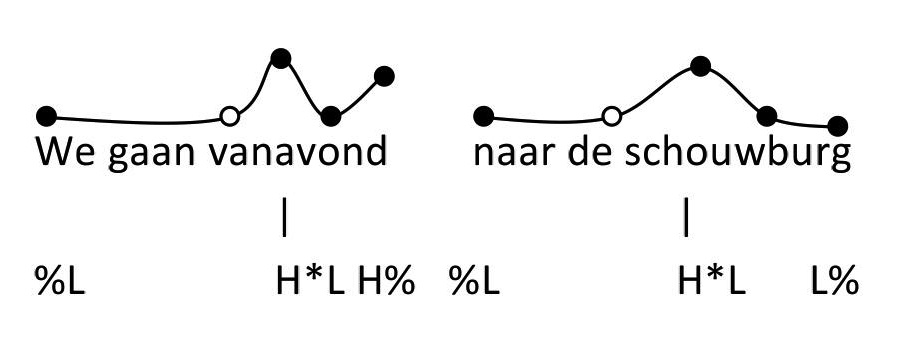

We will go to the theatre tonight

The contour would appear to contradict the regularity outlined above that prenuclear trailing tones are pronounced late, on the assumption that the first pitch accent is H*L. An analysis with H*L on vanavond tonight predicts a slow fall to the rising movement on schouwburg theatre. The steep fall would be expected if there was an IP-boundary after vanavond tonight, but there is no indication that there is any such prosodic break. Taking a different route, we could assume that after the trailing L of the first pitch accent there is another trailing tone H, which has a rightmost target, as is regularly the case for the last trailing tone. This analysis correctly describes the contour, on condition that a tritonal prenuclear pitch accent is introduced, H*LH, as shown in (13).

There are two arguments that can be presented in favour of the analysis in (13). The first is that Hart et al. (1990) defined a rise `5´ which only occurs after the slow rise that follows a prenuclear accent. This `5' has been indicated in the contour in (13), and evidently suggests the presence of two H-targets over de schouw-. It is important to see that the assumption of this additional rise, an acceleration of the slow rise described as `4´, was independent of and predated any tonal theory of Dutch intonation, and therefore represents independent confirmation of the tonal analysis in (7). The second argument is based on the meaning of (13). Its intonation suggests it is an answer to a question about the listener’s plans for the evening. That is, vanavond evening is the topic of the conversation, just as is we we, and constitutes the known information to which additional information is provided in (13): naar de schouwburg to the theatre. The same meaning is expressed in a more explicit way when the topic and the new information are spoken as different IPs. In that case, the topic has a pitch accent H*L followed by H%, as shown in (14). This suggests that (13) has developed from (14) by way of a faster realization, whereby the IP-boundary was lost and H% reinterpreted as a third trailing tone of the prenuclear pitch accent.

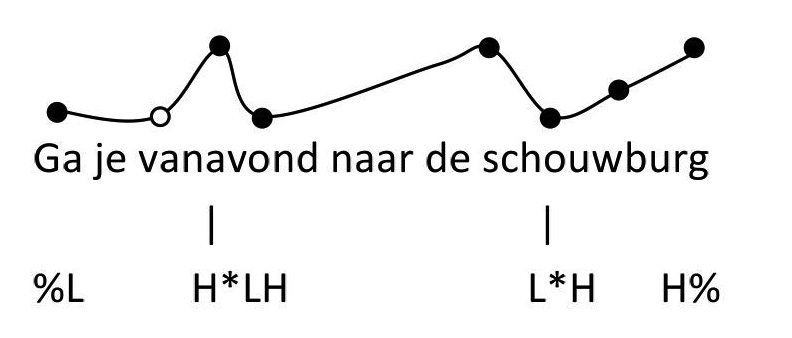

The introduction of H*LH as a prenuclear pitch accent in the grammar predicts that it can combine with other nuclear contours than H*L. This prediction is correct, as shown in (15), for instance, where it occurs before L*H H%. It conveys a high degree of surprise over the timing of the visit to the theatre, announced in response to a preceding statement by the listener about their visit to the theatre that evening.

Are you going to the theatre tonight?

Contour (13) is known in other West Germanic languages, too. It has however, only been described for Dutch so far. Examples of this contour are attested in the recordings of O’Connor and Arnold (1973), where they are depicted as (14).

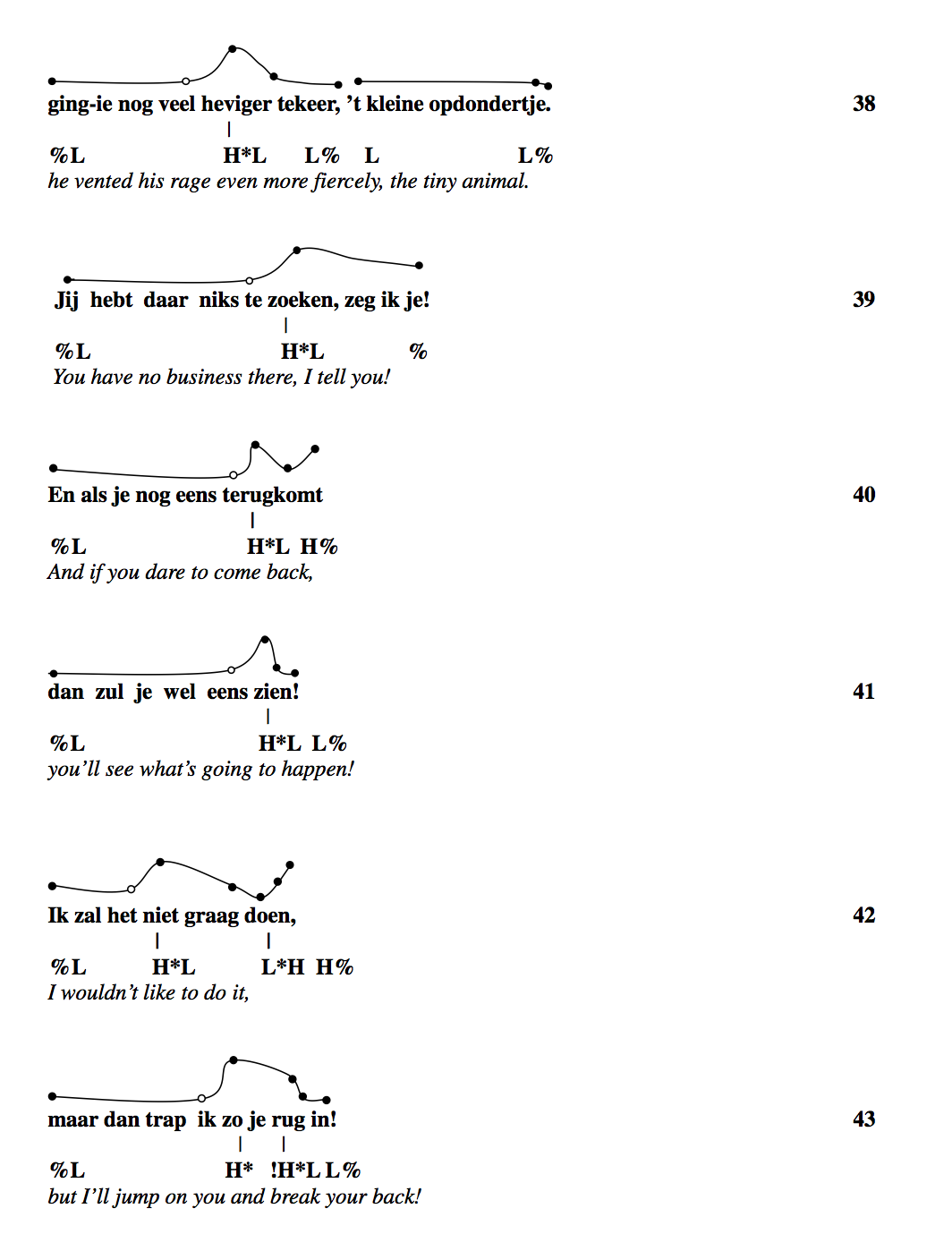

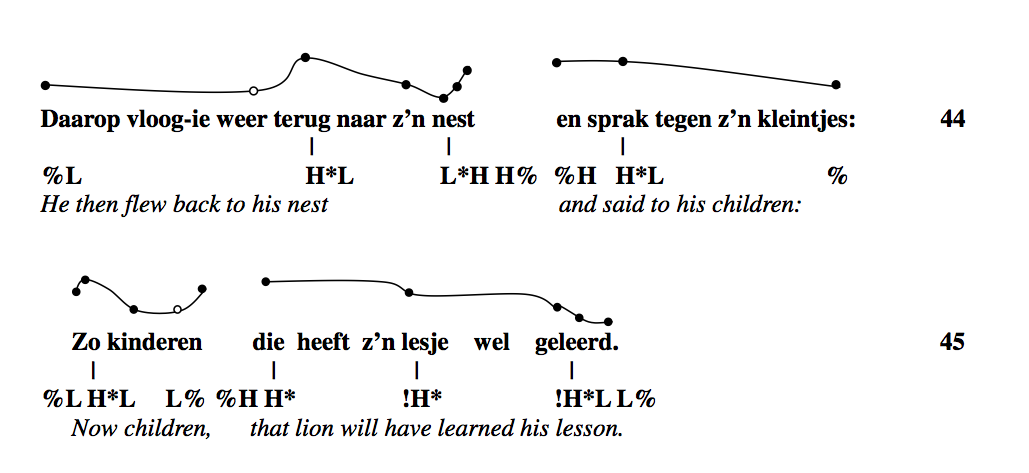

In the following section an example of an intonation transcription is provided. The willow wren was translated from the original Low Saxon De Tunkrüper taken from Wisser (1922). With thanks to Jörg Peters, transcriptions are provided with stylized pitch contours. Each black bullet is the target of a tone, white bullets represent a second target of a tone that has a continued pronunciation. The sound files were obtained from various sources comprising different variants and dialects. In table 1 a complete transcription of all the recordings is given as to provide the reader with the story in one piece, while in table 2 each contour is given separately with its corresponding sound file.

[click image to enlarge]  [click image to enlarge]  [click image to enlarge]  [click image to enlarge]  [click image to enlarge]  [click image to enlarge]  [click image to enlarge]  [click image to enlarge] |

|

- 1922Plattdeutsche Märchen. Ausgabe für ErwachseneJenaDietrichs

- 1998Pre-accentual pitch and speaker attitudes in DutchLanguage and Speech4163-85

- 1995Leading tones and downstep in EnglishPhonology12183-233

- 1995Leading tones and downstep in EnglishPhonology12183-233

- 1983A semantic analysis of the nuclear tones of EnglishBloomington. IULC

- 1993The Dutch foot and the chanted callJournal of Linguistics2937-63

- 2000The behavior of H* and L* under variations in pitch range in Dutch rising contoursLanguage and Speech43183-203

- 2000The behavior of H* and L* under variations in pitch range in Dutch rising contoursLanguage and Speech43183-203

- 1970A Course in Spoken English: IntonationOxford University Press

- 1990A perceptual study of intonation: an experimental-phonetic approach to speech melodyCambridgeCambridge University Press

- 1990A perceptual study of intonation: an experimental-phonetic approach to speech melodyCambridgeCambridge University Press

- 1991Durationally specified intonation in English and BengaliSundberg, Johan, Nord, Lennart & Carlson, Rolf (eds.)Music, language, speech and brain: Proceedings of an international symposium at the Wenner-Gren Center, Stockholm, 5–8 September 1990Basingstoke, UKMacmillan78–91

- 1980The Structure of Intonational Meaning. Evidence from EnglishBloomington. IULC

- 1983Phonological features of intonational peaksLanguage59721-759

- 2003“Sagging transition” between high pitch accents in English: Experimental evidenceJournal of Phonetics3181–112

- 1975The Intonational System of EnglishPhD dissertation. Cambridge, MA. MITThesis

- 1973Intonation of Colloquial EnglishLondonLongman

- 2014The phonetic realization of focus in West Frisian, Low Saxon, High German, and three varieties of DutchJournal of Phonetics46185-209

- 1980The Phonology and Phonetics of English IntonationPhD dissertation. Cambridge, MA. MITThesis

- 1980The Phonology and Phonetics of English IntonationPhD dissertation. Cambridge, MA. MITThesis

- 1980The Phonology and Phonetics of English IntonationPhD dissertation. Cambridge, MA. MITThesis

- 1980The Phonology and Phonetics of English IntonationPhD dissertation. Cambridge, MA. MITThesis

- 1980The Phonology and Phonetics of English IntonationPhD dissertation. Cambridge, MA. MITThesis

- 1980The Phonology and Phonetics of English IntonationPhD dissertation. Cambridge, MA. MITThesis

- 1980The Phonology and Phonetics of English IntonationPhD dissertation. Cambridge, MA. MITThesis