- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

Modality is used as a cover term for various meanings that can be expressed by modal verbs and adverbs. Barbiers (1995:ch.5), for instance, has argued that example (276a) can have the four modal interpretations in (276b).

| a. | Jan | moet | schaatsen. | |

| Jan | must | skate |

| (i) | Dispositional: Jan definitely wants to skate. | ||

| (ii) | Directed deontic: Jan has the obligation to skate. | ||

| (iii) | Non-directed deontic: It is required that Jan skate. | ||

| (iv) | Epistemic: It must be the case that Jan skates. |

The first three interpretations of (276b) can be seen as subcases of event modality and stand in opposition to interpretation (iv), which can be seen as a subcase of propositional modality. The main difference is that event modality expresses the view of the speaker on the moving forces that favor the potential realization of the event referred to by the proposition expressed by the lexical projection of the embedded verb (obligation, volition, ability, etc). Epistemic modality, on the other hand, expresses the view of the speaker on the truth of this proposition (necessity, probability, likelihood, etc). The examples in (277) show that the two groups can readily be distinguished syntactically given that they exhibit different behavior in perfect-tense constructions that refer to eventualities preceding speech time n; dispositional/deontic modal verbs appear as non-finite forms in such constructions, whereas epistemic modal verbs normally appear as finite forms; note that this distinction this does not hold for perfect-tense constructions that refer to future eventualities, which can be four-fold ambiguous. We refer the reader to Section 5.2.3.2, sub III, for a more detailed discussion of the distinction between event and epistemic modality.

| a. | Jan heeft | gisteren | moeten | schaatsen. | event modality | |

| Jan has | yesterday | must | skate | |||

| 'Jan had to skate yesterday.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan moet | gisteren | hebben | geschaatst. | epistemic modality | |

| Jan must | yesterday | have | skated | |||

| 'It must be the case that Jan has skated yesterday.' | ||||||

This section will focus on epistemic modality, subsection I starts with a brief discussion of the epistemic modal verbs moeten'must' and kunnen'can', subsection II argues that the verb zullen behaves in all relevant respects as an epistemic modal verb and that the future reading normally attributed to this verb is due to pragmatics, subsection III supports this conclusion by showing that we find the same pragmatic effects with other verb types.

Epistemic modality is concerned with the mental representation of the world of the language user, who may imagine states of affairs different from what they are in the actual world, states of affairs as they will hold in the future, etc. Consider the examples in (278).

| a. | Dat huis | stort | in. | |

| that house | collapses | prt. | ||

| 'It is the case that that house collapses.' | ||||

| b. | Dat huis | moet | instorten. | |

| that house | has.to | prt.-collapse | ||

| 'It must be the case that that house will collapse.' | ||||

| c. | Dat huis | kan | instorten. | |

| that house | may | prt.-collapse | ||

| 'It may be the case that that house will collapse.' | ||||

By uttering sentences like these the speaker provides his estimation on the basis of the information available to him of the likelihood that eventuality k will actually occur. Under the default (non-future) reading of (278a), the speaker witnesses the collapse of the house. In the case of (278b) and (278c) there is no collapse at speech time n, but the speaker asserts something about the likelihood of a future collapse. By uttering (278b) or (278c), the speaker in a sense quantifies over a set of possible, that is, not (yet) actualized worlds: the modal verb moeten 'must' functions as a universal quantifier, which is used by the speaker to assert that the eventuality of that house collapsing will take place in all possible worlds; kunnen 'may' , on the other hand, functions as an existential quantifier, which is used by the speaker to assert that this eventuality will take place in at least one possible world. Note in passing that the future reading triggered by the epistemic modal verbs need not be attributed to the modal verb itself given that example (278a) can also be used with a future reading; see Section 1.5.4 for more discussion of this.

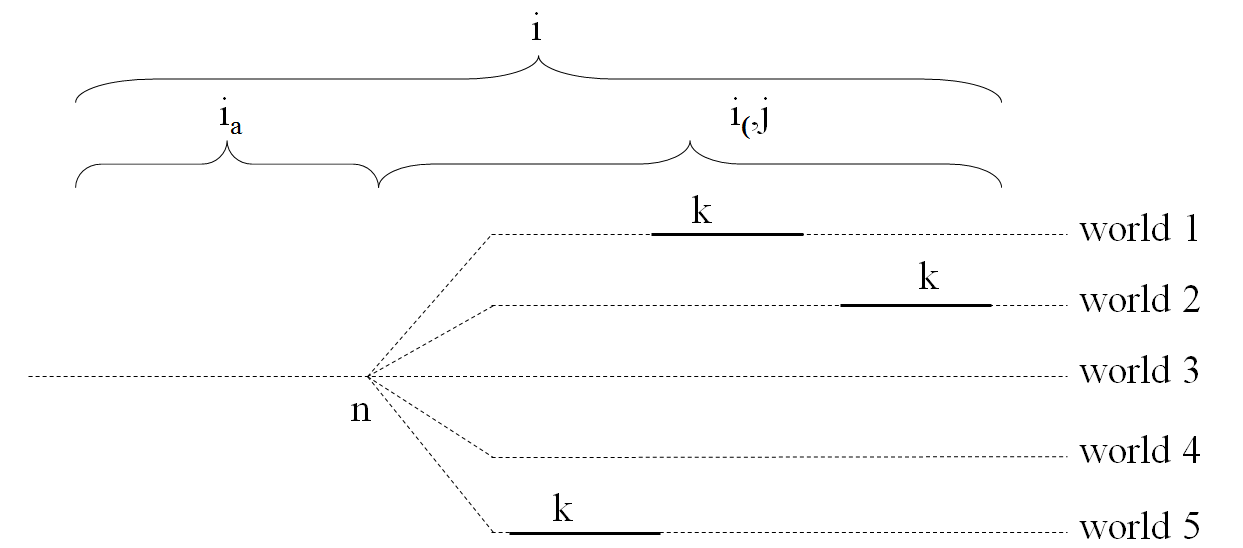

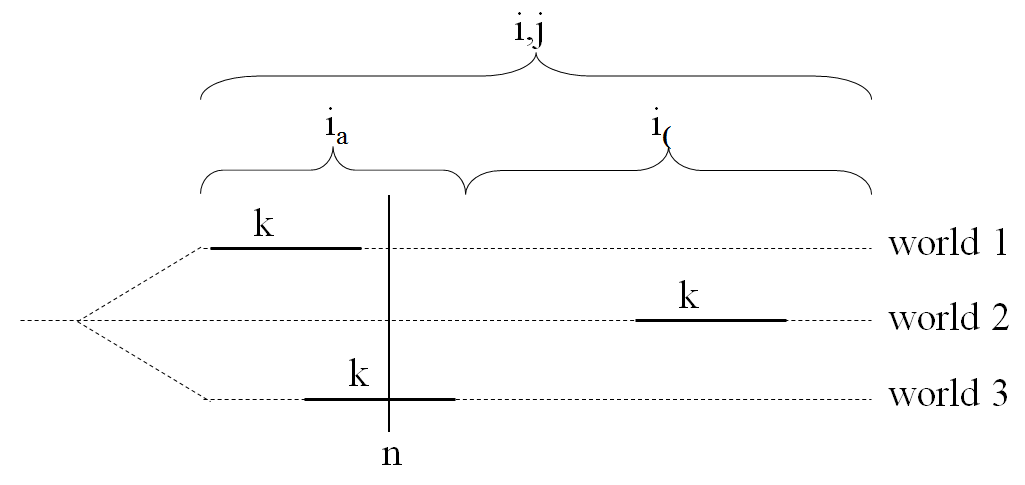

We will represent the meaning of examples like (278b&c) by means of temporal diagrams of the type in Figure 20, which are essentially the same as the ones introduced in Section 1.5.1 with the addition of possible worlds. Again, n stands for the speech time, i stands for the present of the speaker/hearer, ia for the actualized and i◊ for the non-actualized part of this present. The index k stands for the event denoted by the lexical projection of the embedded main verb and the continuous line below it for the actual running time of k . Index j , finally, represents the present of k , that is, the temporal domain within which k must be located. The possible worlds in Figure 20 may differ with respect to (i) whether eventuality k does or does not occur, as well as (ii) the precise location of eventuality k on the time axis. Possible world representations like Figure 20 are, of course, simplifications in the sense that they select a number of possible worlds that suit our illustrative purposes from an in principle infinite set of possible worlds.

Figure 20 is a correct semantic representation of the assertion in example (278c) with existential kunnen given that there is at least one possible world in which the eventuality denoted by the lexical projection of the embedded main verb takes place, but it is an incorrect representation of the assertion in (278b) with universal moeten because the eventuality does not take place in possible worlds 3 and 4.

The examples in (279) show that epistemic modal verbs can readily occur in the past tense. The additions of the particle/adverbial phrase within parentheses will make these examples sound more natural in isolation, but they are also perfectly acceptable without them in a proper discourse.

| a. | Dat huis | moest | (wel) | instorten. | |

| that house | had. to | prt | prt.-collapse | ||

| 'It had to be the case that that house would collapse.' | |||||

| b. | Dat huis | kon | (elk moment) | instorten. | |

| that house | might | any moment | prt.-collapse | ||

| 'It might have been the case that that house would collapse any moment.' | |||||

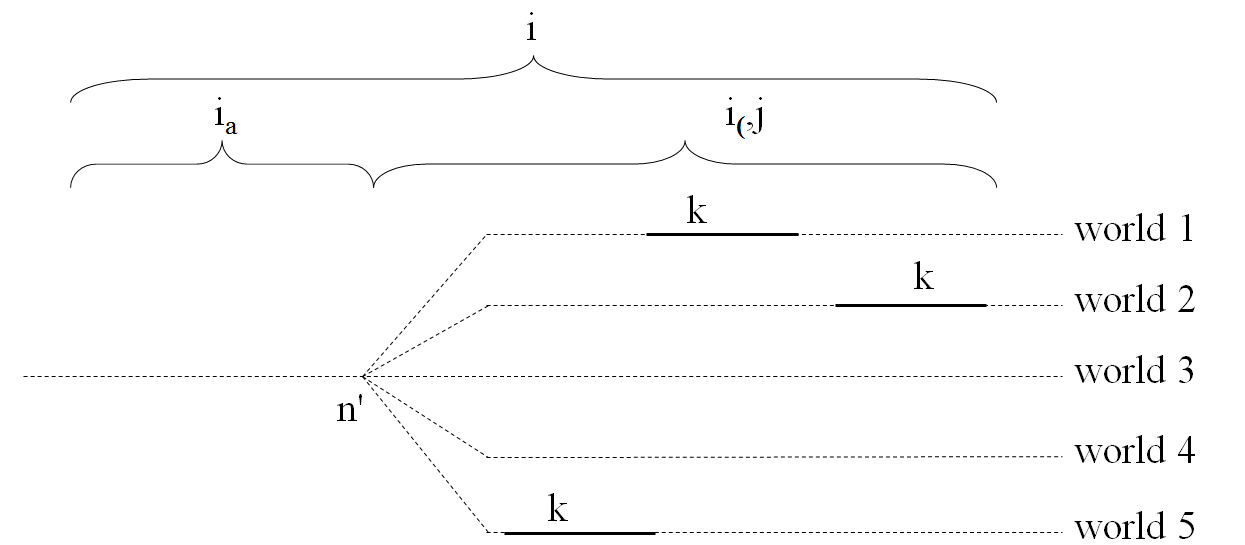

Now consider the representation in Figure 21, in which n' stands for the virtual speech-time-in-the past that functions as the point of perspective, and i stands for the relevant past-tense interval. Figure 21 is a correct representation of the assertion in (279b) given that there are possible worlds in which eventuality k takes place, but an incorrect representation of the assertion in (279a) given that there are possible worlds in which eventuality k does not take place. Figure 21 is again a simplification; it selects a number of possible worlds that suit our illustrative purposes from an in principle infinite set of possible worlds. From now on our semantic representations will contain only the minimal selection of possible worlds that is needed to illustrate our point.

It should further be noted that examples such as (279) are normally used if speech time n is not included in the past-tense interval. Examples such as (279a) are used if eventuality k did take place before n in order to suggest that the occurrence of k was inevitable. Examples such as (279b), on the other hand, are used especially if eventuality k did not take place in the actual world in order to suggest that certain measures have prevented k from taking place, that we are dealing with a lucky escape, etc. We will return to these restrictions on the usage of the examples in (279) in Section 1.5.2, sub IIC, and confine ourselves here to noting that the epistemic modals differ in this respect from their deontic counterparts, which normally do not carry such implications: the past-tense construction with deontic moeten in (280), for example, may refer both to factual and counterfactual situations.

| Jan moest | verleden week | dat boek | lezen, ... | ||

| Jan had. to | last week | that book | read | ||

| 'Jan had the obligation to read that book last week, ...' | |||||

| a. | ... | maar | hij | heeft | het | niet | gedaan. | counterfactual | |

| ... | but | he | has | it | not | done | |||

| '... but he didnʼt do it.' | |||||||||

| b. | ... | en | het | is hem | met veel moeite | gelukt. | factual | |

| ... | and | it | is him | with much trouble | succeeded | |||

| '... and he has managed to do it with much trouble.' | ||||||||

In Figure 20 and Figure 21, the splitting point into possible worlds (from now on: split-off point) starts at n or n'. This is, however, by no means necessary. Suppose the following context. There has been a storm last week and on Sunday the speaker inspected his weekend house and saw that it was seriously damaged. Since it will remain stormy this week the speaker has worries about what will happen to the house and on Tuesday he expresses these by means of the utterance in (281).

| Mijn huis | moet | deze week | instorten. | ||

| my house | has.to | this week | prt.-collapse | ||

| 'It must be the case that my house will collapse this week.' | |||||

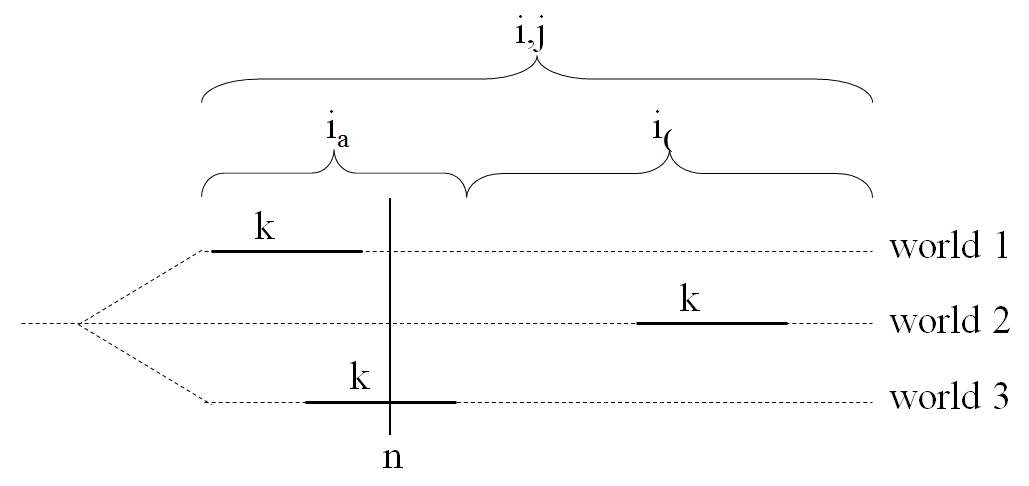

Given that the speaker does not know whether the house is still standing at n, the utterance refers to the situation depicted in Figure 22, in which the split-off point is situated at the moment that the speaker left the house on Sunday; the present j of eventuality k, which is specified by the adverbial phrase deze week'this week', therefore starts on Monday and ends on Sunday next. In this situation it is immaterial whether eventuality k precedes, overlaps with or follows n.

The fact that k can be located anywhere within time interval j is related to the fact that the speaker has a knowledge gap about his actual world; he simply does not know at n whether the house is still standing, that is, in which possible world he is actually living. In fact, this is made explicit in (282) by the addition of a sentence that explicitly states that the collapse may already have taken place at speech time n.

| Mijn huis moet | deze week | instorten. | Mogelijk | is | het | al | gebeurd. | ||

| my house has.to | this week | prt.-collapse | possibly | is | it | already | happened | ||

| 'It must be the case that my house collapsed or will collapse this week. Possibly it has already happened.' | |||||||||

The situation is quite different, however, when the knowledge of the speaker is up-to-date. Suppose that the speaker is at the house with someone on Tuesday and that he utters the sentence in (283).

| Dit huis | moet | deze week | instorten. | ||

| this house | has.to | this week | prt.-collapse | ||

| 'It must be the case that this house will collapse this week.' | |||||

From this utterance we now will conclude that the house is still standing at speech time n, and infer from this that it is asserted that the collapsing of the house will take place in the non-actualized part of the present-tense interval i◊. This is, however, not a matter of semantics but of pragmatics. The infelicity of utterance (283) in a world in which the speaker already knows that the house has collapsed follows from Grice's (1975) maxim of quantity given that the speaker could describe that situation more accurately by means of the perfect-tense construction in (284), which places the eventuality in the actualized part of the present-tense interval ia; see Section 1.5.4.2.

| Dit huis | is | deze week | ingestort. | ||

| this house | has | this week | prt.-collapsed | ||

| 'This house has collapsed this week.' | |||||

The observations concerning (283) and (284) show that the simple present can only be used to refer to an eventuality preceding speech time n if the speaker is underinformed: if he has more specific information about the location of the eventuality, he will use the tense form that most aptly describes that location. As a result, example (282) does not primarily provide temporal information concerning the eventuality of a collapse but information about the necessity of this eventuality.

We conclude with an observation that is closely related to this. The past-tense counterpart of (281) can also be followed by a sentence that explicitly states that the collapse may already have taken place at speech time n. We assume here the same situation as for (282): the sentence uttered on Tuesday looks back to some virtual speech-time-in-the-past at which it was said that the house would collapse during the time interval referred to by the adverbial phrase deze week'this week', that is, a time interval that includes speech time n. Given that the speaker is underinformed about the actual state of his house, what counts is not the actual eventuality of a collapse but the necessity of this eventuality.

| Mijn huis moest | deze week | instorten. | Mogelijk | is | het | al | gebeurd. | ||

| my house had.to | this week | prt.-collapse | possibly | is | it | already | happened | ||

| 'It had to be the case that my house will collapse this week. Possibly it has already happened.' | |||||||||

The observations in (282) and (285) show that the use of an epistemic modal shifts the attention from the actual location of eventuality k within the interval j to epistemic information; the speaker primarily focuses on the necessity, probability, likelihood, etc. of the occurrence of eventuality k within j. Information about the precise location of k is of a secondary nature and dependent on contextual information that determines the split-off point of possible worlds as well as information about the knowledge state of the speaker. Our findings are summarized in (286).

| Temporal interpretation of epistemic modal, simple present/past constructions: |

| a. | If the split-off point of the possible worlds is located at speech time n, eventuality k cannot be situated in the actualized part ia of the present/past-tense interval because the maxim of quantity would then favor a present/past perfect-tense construction. |

| b. | If the split-off point of the possible worlds precedes speech time n, the temporal interpretation depends on the knowledge state of the speaker: | |

| (i) if the speaker is underinformed, that is, not able to immediately observe whether eventuality k has taken place, eventuality k can be situated before speech time n. | ||

| (ii) if the speaker is not underinformed, that is, able to immediately observe whether eventuality k has taken place, eventuality k cannot be situated before speech time n, because the maxim of quantity would then favor a present/past perfect-tense construction. |

The binary tense system discussed in Section 1.5.1 takes zullen in examples such as (287a) as a future auxiliary. However, it is also claimed that zullen can be used as an epistemic modal verb in examples such as (287b); cf. Haeseryn et al. (1997:944). On this view there are two verbs zullen, one temporal, and the other modal.

| a. | Marie zal | dat boek | morgen | versturen. | temporal: future | |

| Marie will | that book | tomorrow | send | |||

| 'Marie will send that book tomorrow.' | ||||||

| b. | Marie zal | dat boek | wel | versturen. | modal: probability | |

| Marie will | that book | prt | send | |||

| 'It is very likely that Marie will send that book.' | ||||||

That zullen need not function as a future auxiliary is also clear from the fact that examples with zullen of the type in (288b) behave similar as examples with epistemic moeten/kunnen'must/may' in (288a) in that they refer to an eventuality k that overlaps with speech time n as is clear from the use of the adverb nu'now'.

| a. | Het | is vier uur. | Marie moet/kan | nu | wel | thuis | zijn. | |

| it | is 4.00 p.m. | Marie must/may | now | prt | at.home | be | ||

| 'It is 4.00 p.m. Marie must/may be at home now.' | ||||||||

| b. | Het | is vier uur. | Marie zal | nu | wel | thuis | zijn. | |

| it | is 4.00 p.m. | Marie will | now | prt | at.home | now | ||

| 'It is 4.00 p.m. Marie will be at home now.' | ||||||||

The examples in (287) and (288) do not necessarily lead to the conclusion that zullen is homonymous. The fact discussed in Subsection I that epistemic verbs like moeten/kunnen can also be used in examples with a future interpretation in fact suggests that zullen functions as an epistemic modal throughout; see Janssen (1983/1989), and also Erb (2001), who concludes the same thing for German werden'will'. The following subsections will more extensively motivate this conclusion.

The claim that zullen is homonymous is often motivated by the meaning attributed to sentences such as (287). Example (287a) strongly suggests that the eventuality of Marie sending that book will take place tomorrow, thus giving room to the idea that the information is primarily about the location of the eventuality with respect to speech time n and therefore essentially temporal. The idea is then that (287b) is about whether or not Marie will send that book and the speaker finds it probable that she will; we are dealing with epistemic modality—temporality is not a factor.

A contrast between a temporal and a probability reading should come out by adding the conjunct ... maar je weet het natuurlijk nooit echt zeker'... but one never knows for sure, of course' as this should lead to an acceptable result with sentences expressing probability only; in sentences expressing future the result should be semantically incoherent given that the added, second clause contradicts the presumed core meaning of the first clause. That this does not come true is shown by the fact that both examples in (289) are fully acceptable.

| a. | Marie zal | dat boek | morgen | versturen ... | (maar | je | weet | het | natuurlijk | nooit | echt | zeker | bij haar). | |

| Marie will | that book | tomorrow | send | but | you | know | it | of.course | never | really | certain | with her | ||

| 'Marie will send that book tomorrow (although one never knows for sure with her, of course).' | ||||||||||||||

| b. | Marie zal | dat boek | wel | versturen .... | (maar | je | weet | het | natuurlijk | nooit | echt | zeker | bij haar). | |

| Marie will | that book | prt | send | but | you | know | it | of.course | never | really | certain | with her | ||

| 'It is very likely that Marie will send that book (although one never knows for sure with her, of course).' | ||||||||||||||

Haeseryn et al. (1997:994) note that examples with a probability reading normally include the modal particle wel, which opens the possibility that the probability reading is not part of the meaning of the verb zullen but should be ascribed to the particle. This suggestion is supported by the fact that examples such as (290) receive a probability reading without the help of the verb zullen, and it is also consistent with the fact that Van Dale's dictionary simply classifies wel as a modal adverb that may express a conjecture or doubt.

| Marie stuurt | dat boek | wel. | ||

| Marie sends | that book | prt | ||

| 'It is very likely that Marie will send that book.' | ||||

If wel is indeed responsible for the probability meaning of examples such as (287b), it is no longer clear that the two occurrences of zullen in (287) differ in meaning. That these occurrences may have identical meanings might be further supported by the fact that the two examples in (287) receive similar quantificational force when we add modal adverbs like zeker'certainly' or misschien'maybe', as in (291).

| a. | Marie zal | dat boek | morgen | zeker/misschien | sturen. | |

| Marie will | that book | today | certainly/maybe | send | ||

| 'It will certainly/maybe be the case that Marie will send that book tomorrow.' | ||||||

| b. | Marie zal | dat boek | zeker/misschien | wel | sturen. | |

| Marie will | that book | certainly/maybe | prt | send | ||

| 'It will certainly/maybe be the case that Marie will send that book.' | ||||||

The acceptability of (291b) would be surprising if the meaning aspect "probably" of (287b) is due to the meaning of zullen. First, this presumed meaning of zullen is inconsistent with the meaning "certainly" expressed by the adverb zeker, and we would therefore wrongly predict example (291b) to be semantically incoherent with this adverb. Second, this presumed meaning aspect of zullen is very similar to the meaning expressed by the adverb misschien'maybe' and example (291b) would therefore be expected to have the feel of a tautology with this adverb. The fact that this is not borne out again suggests that the probability meaning aspect of (287b) is due to the modal particle wel, which can also be supported by the fact illustrated in (292) that the combinations zeker wel and misschien wel can also be used to express epistemic modality in constructions without zullen. We therefore conclude that the two occurrences of zullen in (287) are semantically more similar than is often assumed, if not identical.

| a. | Marie stuurt | dat boek | zeker | wel. | |

| Marie sends | that book | certainly | prt | ||

| 'It is virtually certain that Marie will send the book.' | |||||

| a'. | Stuurt | Marie | dat boek? | ja, | zeker | wel. | |

| sends | Marie | that book | yes | certainly | prt | ||

| 'Will Marie send the book? Yes, definitely.' | |||||||

| b. | Marie stuurt | dat boek | misschien | wel. | |

| Marie sends | that book | maybe | prt | ||

| 'It isnʼt excluded that Marie will send the book.' | |||||

| b'. | Stuurt | Marie | dat boek? | ja, | misschien | wel. | |

| sends | Marie | that book | yes | maybe | prt | ||

| 'Will Marie send the book? Yes, maybe.' | |||||||

That the two occurrences of zullen in (287) are similar is less easy to establish on the basis of their morphosyntactic behavior. At first sight, the primeless sentences in (293) seem to show that, like the epistemic modals moeten and kunnen, both occurrences of zullen appear as the finite verb in the corresponding perfect-tense constructions that refer to eventualities preceding speech time n, whereas the primed examples seem to show that they do not allow the syntactic format normally found with deontic modals; see the discussion of the examples in (277) in the introduction to Section 1.5.2. The problem with this argument, however, is that some readers will reject the idea that the (a)-examples with gisteren'yesterday' involve temporal zullen simply because we are dealing with an eventuality preceding n in that case. We nevertheless include this argument given that it should be valid for readers that follow, e.g., Hornstein's (1990) implementation of Reichenbach's tense system, which in fact predicts that the future perfect can refer to eventualities preceding speech time n.

| a. | Marie | zal | dat boek | gisteren | hebben | verstuurd. | |

| Marie | will | that book | yesterday | have | sent | ||

| 'Marie will have sent that book yesterday.' | |||||||

| a'. | * | Marie heeft | dat boek | gisteren | zullen | versturen. |

| Marie has | that book | yesterday | will | sent |

| b. | Marie | zal | het boek | gisteren | wel | verstuurd | hebben. | |

| Marie | will | the book | yesterday | probably | sent | have | ||

| 'Marie will probably have sent the book yesterday.' | ||||||||

| b'. | * | Marie heeft | het boek | gisteren | wel | zullen | versturen. |

| Marie has | the book | yesterday | probably | will | send |

We will not, however, press this argument any further and conclude this subsection by observing that the past-tense counterpart of example (293a') seems fully acceptable. However, examples such as (294) are irrealis constructions of a special type, in which hebben does not seem to function as a perfect auxiliary.

| Marie had dat boek | gisteren | zullen | versturen | (maar | ze had geen tijd). | ||

| Marie had that book | yesterday | will | sent | but | she had no time | ||

| 'Marie would have sent that book yesterday (but she couldnʼt find the time).' | |||||||

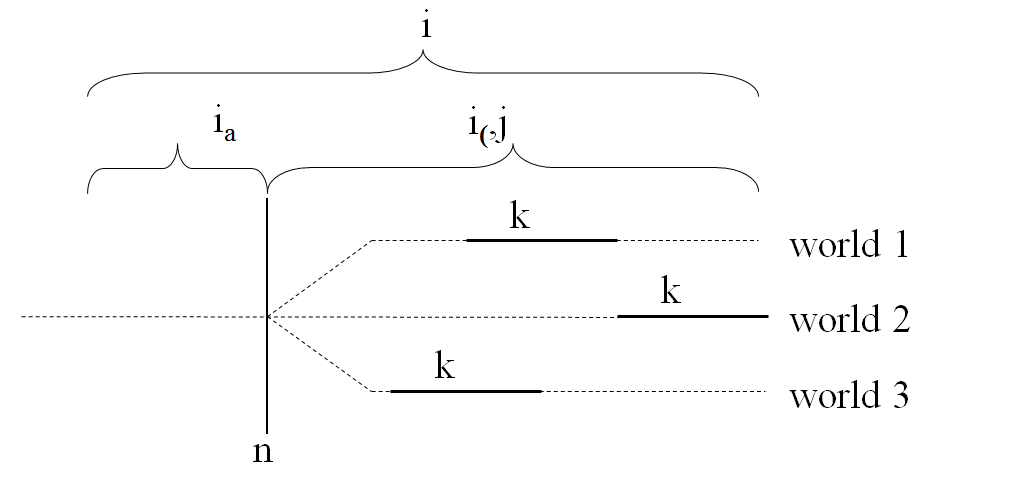

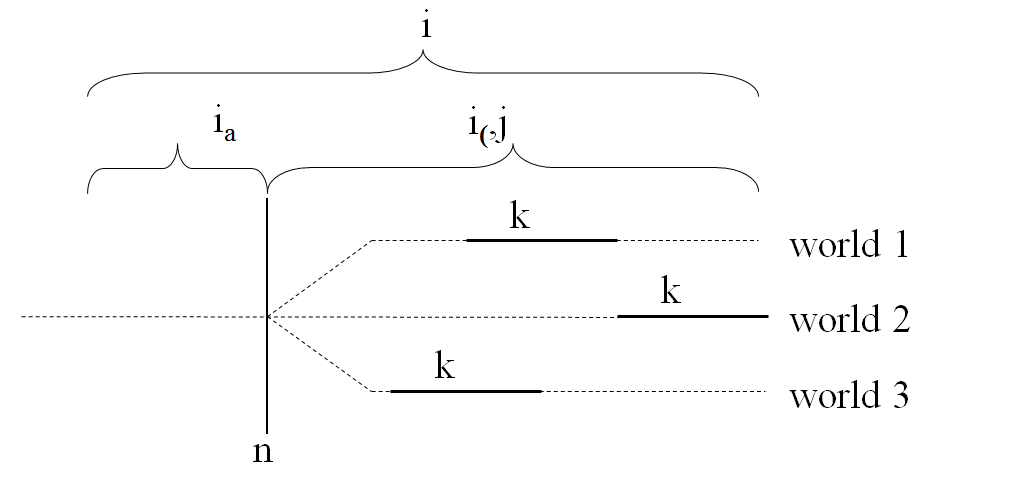

If the two occurrences of zullen in (287) are not homonymous but representatives of a single category, we will have to establish whether we are dealing with a future auxiliary or with an epistemic modal. If zullen is a future auxiliary, we would expect the use of its present-tense forms to have the effect of locating eventuality k in non-actualized part i◊ of the present-tense interval, as indicated in Figure 23, where we assume n to be the split-off point for the possible worlds; note that we have seen earlier that zullen does not imply that eventuality k takes place in all possible worlds, but we ignore this for the moment for simplicity.

If zullen is an epistemic modal, on the other hand, we would expect that its present-tense forms are also possible if the split-off point precedes n and eventuality k is located in the actualized part ia of the present-tense interval, as in . Since the examples in (288) in the introduction to this subsection have already shown that in certain examples with zullen eventuality k may overlap with speech time n , the discussion below will focus on whether k may also precede n .

The representation in Figure 24 is essentially the one that we gave in Figure 22 for example (282) with epistemic moeten 'must' ; the main difference involves the fact not indicated here that whereas moeten is truly a universal quantifier, the use of zullen does not imply that the speaker asserts that eventuality k will take place in all possible worlds. This means that we can easily test whether zullen can be used epistemically by considering the result of replacing moeten in (282) by zullen , as in (295).

| Mijn huis | zal | deze week | instorten. | Mogelijk | is | het | al | gebeurd. | ||

| my house | will | this week | prt.-collapse | possibly | is | it | already | happened | ||

| 'My house will collapse this week. Possibly it has already happened.' | ||||||||||

Now, assume the same context as for (282): there has been a storm last week and on Sunday the speaker inspected his weekend house and saw that it was seriously damaged. Since it has remained stormy, the speaker has worries about the house and on Tuesday he expresses these worries by means of uttering sentence (295). In this context, this sentence would be considered true if the house had already collapsed on Monday, as in world 1 of Figure 24, and we can therefore conclude that zullen indeed exhibits the semantic hallmark of epistemic modals.

As in the case of moeten and kunnen , the unambiguous future readings in Figure 23 should be seen as the result of pragmatics. This will become clear when we replace the modal moeten in example (283) by zullen , as in (296a). The proximate demonstrative dit in dit huis 'this house' suggests that the speaker is able to evaluate the actual state of the house at speech time n. It now follows from Grice's (1975) maxim of quantity that (296a) can only be used if the house is still standing: if the house is already in ruins at n , the speaker could, and therefore would have expressed this more accurately by using the perfect-tense construction in (296b).

| a. | Dit huis | zal | deze week | instorten. | |

| this house | will | this week | prt.-collapse | ||

| 'This house will collapse this week.' | |||||

| b. | Dit huis | is | deze week | ingestort. | |

| this house | has | this week | prt.-collapse | ||

| 'This house has collapsed this week.' | |||||

In the situation just described, a simple present sentence such as (297) would also receives a future interpretation for the same pragmatic reason; if the house is already in ruins at n, the speaker again could have expressed this more accurately by the perfect-tense construction in (296b). This shows that the future reading of (296c) is independent of the use of the verb zullen .

| Dit huis | stort | deze week | in. | ||

| this house | collapses | this week | prt. | ||

| 'This house will collapse this week.' | |||||

Note, finally, that the speaker who uttered sentence (295) could also have used the sentence in (298) given that the two examples express virtually identical meanings; compare the discussion of moeten in sentences like (282) and (285).

| Mijn huis zou | deze week | instorten. | Mogelijk | is | het | al | gebeurd. | ||

| my house would | this week | prt.-collapse | maybe | is | it | already | happened | ||

| 'My house would collapse this week. Maybe it has already happened.' | |||||||||

The possibility that the house still stands at speech time n is not only left open in (295), but also in (298). This is due to the fact that speech time n can be included in past-tense interval i; see the definition of +past in Section 1.5.1, sub C, example (249b). The two examples differ, however, in the perspective from which the information about eventuality k is presented. In (295) the information is presented from the perspective of the actual speech time n of the speaker/hearer, as is clear from the fact that it can be followed by the present-tense clause … zo is mij verteld 'so I am told' . In (298), on the other hand, the information is presented from the perspective of the virtual speech-time-in-the pastn', as is clear from the fact that it can only be followed by a past-tense clause: … zo werd mij verteld 'so I was told' . This suggests that the choice between present and past tense is determined by the wish to speak about eventuality k on the basis of information available within, respectively, a specific present-tense interval i or a specific past-tense interval i.

That eventuality k can precede speech time n can also be illustrated by means of non-telic predicates; see Janssen (1983). An example such as (299) is three ways ambiguous when it comes to the location of eventuality k . First, if the speaker and hearer know that Jan has already departed, the speaker can use (299) to express his expectation that Jan has already travelled for three hours at the moment of speech ( k < n ). Second, if the speaker and hearer know that Jan has departed one hour earlier, the speaker can use (299) to express his expectation that Jan will arrive in two hours ( n is included in k ). Third, if the speaker and hearer know that Jan has not yet departed, (299) can be used to express the speaker's expectation that Jan will undertake a future journey that lasts three hours ( n < k ).

| Jan zal | in totaal | drie uur | onderweg | zijn. | ||

| Jan will | in total | three hours | on.the.road | be | ||

| 'Jan will be on the road for three hours.' | ||||||

Note, however, that the three readings of (299) differ in their implications for the duration of Jan's travel. The first reading ( k < n ) can be used if the speaker knows the complete journey will take longer than three hours, whereas under the second and third reading the speaker expresses that the journey will take three hours. We assume that this is a side effect of the fact that the first reading implies some evaluation time that is identical to speech time, which could be made explicit by means of the adverb nu 'now' . When we overrule this default evaluation time by adding an adverbial phrase like morgenmiddag om drie uur 'at 3:00 p.m. tomorrow' , the future reading ( k < n ) of this example will also allow the reading that the journey will take longer than three hours. If we put this side effect aside, we can conclude that the three way ambiguity of (299) with respect to the location of k shows that examples with zullen can have the temporal representation in Figure 24, and, hence, that zullen is not a future auxiliary.

This subsection has shown that the interpretation of simple present/past-tense constructions with the verb zullen proceeds in a way similar to the interpretation of simple present/past constructions with the epistemic modals moeten 'must' and kunnen 'may' . This means especially that in both cases inferences about the precise location of eventuality k (that is, whether it is situated before or after speech time n) are made along the lines sketched in (286) in Subsection I. We take this to be a conclusive argument for assuming that zullen is not a future auxiliary; see Janssen (1983) for a similar line of reasoning.

Now that we have established that zullen is not a future auxiliary, we can conclude that it is an epistemic modal verb. This subsection tries to establish more precisely what its meaning contribution is.

It seems that zullen'will' differs from epistemic modal verbs like moeten'must' and kunnen'may' in that it does not have any inherent quantificational force. This will be clear from the examples in (300), in which the quantificational force must be attributed to the modal adverbs: zeker'certainly' expresses universal quantification over possible worlds, mogelijk/misschien'possibly' expresses a low degree of probability, and waarschijnlijk'probably' expresses a high degree of probability.

| a. | Dit huis | zal | deze week | zeker | instorten. | universal | |

| this house | will | this week | certainly | prt.-collapse | |||

| 'This house will certainly collapse this week.' | |||||||

| b. | Dit huis | zal | deze week | mogelijk/misschien | instorten. | low degree | |

| this house | will | this week | possibly/maybe | prt.-collapse | |||

| 'Possibly/Maybe, this house will collapse this week.' | |||||||

| c. | Dit huis | zal | deze week | waarschijnlijk | instorten. | high degree | |

| this house | will | this week | probably | prt.-collapse | |||

| 'This house will probably collapse this week.' | |||||||

If zullen were inherently quantificational, we would expect the examples in (300) to be degraded or at least to give rise to special effects (which is indeed the case in various degrees when we replace zullen by moeten or kunnen). For example, if zullen were to inherently express universal quantification, the modal adverb zeker in (300a) would be tautologous and the adverbs mogelijk and waarschijnlijk in (300b&c) would be contradictory. And if zullen were to inherently express existential quantification, mogelijk and waarschijnlijk in (300b&c) would be tautologous. Nevertheless, it should be noted that examples like (295) and (296a), which do not contain any element with quantificational force, are normally used if the speaker has strong reason for believing that eventuality k will occur in all possible worlds; high degree quantification therefore seems to be the default reading of sentences with zullen.

In order to describe the meaning contribution of zullen'will', we have to discuss a meaning aspect of epistemic modality that has only been mentioned in passing. Epistemic modality stands in opposition to what is known as metaphysical modality, in which objective truth is the central notion and which is part of a very long philosophical tradition concerned with the reliability of scientific knowledge. Epistemic modality, on the other hand, concerns the degree of certainty assigned to the truth of a proposition by an individual on the basis of his knowledge state (note in this connection that the notion epistemic is derived from Greek episteme'knowledge'). Epistemic modal verbs like moeten'must' and kunnen'can', for example, do not express a degree of probability that is objectively given, but one that results from the assessment of the situation by some individual on the basis of the knowledge available to him. The difference between a declarative clause without a modal verb such as (301a) and a declarative clause with a modal verb such as (301b) is thus that in the former case the proposition that Marie is at home is merely asserted "without indicating the reasons for that assertion or the speaker's commitment to it" (Palmer 2001:64), whereas in the latter the modal verb indicates "that a judgment has been made or that there is evidence for the proposition" (Palmer 2001:68).

| a. | Marie is nu | thuis. | |

| Marie is now | at.home | ||

| 'Marie is at home now.' | |||

| b. | Marie moet/kan | nu | thuis | zijn. | |

| Marie must/may | now | at.home | be | ||

| 'Marie must/may be at home now.' | |||||

In his Kritik der reinen Vernunft (1781) Immanuel Kant already distinguished three types of epistemic modality, which he called problematical, apodeictical and assertorical modality. Palmer (2001) makes essentially the same distinctions in Section 2.1; he refers to the three types as speculative, deductive and assumptive modality. Illustrations are given in (302).

| a. | Marie kan | nu | thuis | zijn. | problematic/speculative | |

| Marie may | now | at.home | be |

| b. | Marie moet | nu | thuis | zijn. | apodeictical/deductive | |

| Marie must | now | at.home | be |

| c. | Marie zal | nu | thuis | zijn. | assertorical/assumptive | |

| Marie will | now | at.home | be |

By uttering examples such as (302), the speaker provides three different epistemic judgments about (his commitment to the truth of) the proposition Marie is at home. The use of kunnen 'may' in (302a) presents the proposition as a possible conclusion: the speaker is uncertain whether the proposition is true, but on the basis of the information available to him he is not able to exclude it. The use of moeten 'must' in (302b) presents the proposition as the only possible conclusion: on the basis of information available the speaker concludes that it is true. The use of zullen 'will' in (302c), finally, presents the proposition as a reasonable but uncertain conclusion on the basis of the available evidence; see also Droste (1958:311) and Janssen (1983/1989). Palmer (2001) further suggests that the evidence involved may include experience and generally accepted knowledge as in Het is vier uur; Marie kan/moet/zal nu thuis zijn'It is 4.00 p.m.; Marie may/must/will be at home now'. Note that contrary to what Palmer (2001: section 2.1.2) suggests, we believe that (at least in Dutch) this holds not only for assumptive but for all types of epistemic modality.

The claim that epistemic modality involves some subjective assessment is completely compatible with our earlier claim that epistemic modality introduces a set of possible worlds. The term possible world in fact only makes sense if such a world is accessible, that is, if one can, in principle, enter it from the one that counts as the point of departure. Thus, the creation of a point of perspective is—however metaphorically expressed—an essential ingredient of the notion of possible world; "Suppose now that someone living in w1 is asked whether a specific proposition, p, is possible (whether p might be true). He will regard this as the question as to whether in some conceivable world (conceivable, that is, from the point of view of his world, w1), p would be true …" (Hughes & Cresswell 1968:77).

That we are dealing with subjective assessments is clear from the fact that examples such as (303a) are definitely weird; the modals moeten and kunnen express that the suggested probability of the sun rising is just the result of an assessment by the speaker, who thereby suggests that the alternative view of the sun not rising tomorrow might in principle also be viable. Example (303b) shows that the modal zullen likewise gives rise to a weird result; examples like these are only possible if stating the obvious has some rhetoric function as in Maak je niet druk, de zon zal morgen ook wel opkomen'Donʼt get upset, the sun will rise tomorrow just the same'. Janssen (1983) suggests that the markedness of the examples in (303) follows from Grice's maxim of quantity; the expression of doubt makes the utterances more informative than is required.

| a. | $ | De zon | moet/kan | morgen | op | komen. |

| the sun | has.to/may | tomorrow | up | come | ||

| 'The sun must/may rise tomorrow.' | ||||||

| b. | $ | De zon | zal | morgen | op | komen. |

| the sun | will | tomorrow | up | come | ||

| 'The sun will rise tomorrow.' | ||||||

That epistemic modals imply an assessment by some individual may also be supported by the fact that examples like (304a&b) are completely acceptable if uttered by an amateur astronomer who has calculated for the first time in his life the time of the rising of the sun on a specific day; in these cases the possibility that the sun rises at some other time than indicated is indeed viable, as the speaker may have made some miscalculation. The expression of doubt in these examples is thus in accordance with the maxim of quantity.

| a. | De zon | moet | morgen | om 6.13 | op | komen. | |

| the sun | has.to | tomorrow | at 6:13 | up | come | ||

| 'The sun must rise at 6:13 a.m. tomorrow.' | |||||||

| b. | De zon | zal | morgen | om 6:13 | op | komen. | |

| the sun | will | tomorrow | at 6.13 | up | come | ||

| 'The sun will rise at 6:13 a.m. tomorrow.' | |||||||

That subjective assessment is an essential part of the meaning of epistemic modal verbs is perhaps clearer in English than in Dutch given that epistemic clauses require that a modal verb be used in the English, but not the Dutch, simple present. This difference can be formulated as in (305): English obeys the material implication in (305a), from which we can derive (305a') by modus tollens (the valid argumentation form in propositional logic according to which we may conclude from P → Q and ¬Q that ¬P); Dutch, on the other hand, has the material implication in (305b), from which we cannot derive the statement in (305b') as that would be a formal fallacy.

| a. | English: | subjective assessment → modal present |

| a'. | no modal present → no subjective assessment | valid inference |

| b. | Dutch: | modal present → subjective assessment |

| b'. | no modal present → no subjective assessment | invalid inference |

From this difference it follows that the Dutch simple present can be used in a wider range of "future" constructions than the English simple present. Comrie (1985:118) has claimed that the English simple present construction can only be used to refer to future states of affairs if we are dealing with what he calls scheduled events (such as the rising of the sun, the departure of a train, etc.). Under the reasonable assumption that scheduled events do not involve a subjective assessment, this is correctly predicted by the valid inference in (305a').

| a. | * | Jan leaves tomorrow. |

| b. | The train leaves at 8.25 a.m. |

The invalidity of the inference in (305b'), on the other hand, expresses that Dutch is not restricted in the same way as English, but can freely use clauses in the simple present to refer to any future event; see Section 1.5.4 for further discussion.

| a. | Jan | vertrekt | morgen. | |

| Jan | leaves | tomorrow | ||

| 'Jan will leave tomorrow.' | ||||

| b. | De trein | vertrekt | om 8.25 uur. | |

| the train | leaves | om 8.25 hour | ||

| 'The train leaves at 8.25 a.m.' | ||||

Although the presence of an epistemic modal is not forced in contexts of subjective assessment in Dutch, the discussion above has shown that subjective assessment is an inherent part of the meaning of epistemic modals. Note that the person whose assessment is given can be made explicit by means of an adverbial PP. In accordance with the generalizations in (305) such PPs normally require an epistemic modal verb to be present in English present-tense constructions (Carole Boster, p.c.), whereas in Dutch they can also be used without such a modal.

| a. | Volgens Jan | komt | de zon | morgen | om 6.13 uur | op. | |

| according.to Jan | comes | the sun | tomorrow | at 6.13 hour | up | ||

| 'According to Jan the sun will rise at 6.13 a.m. tomorrow.' | |||||||

| a'. | *? | According to John the sun rises at 6.13 a.m. tomorrow. |

| b. | Volgens Jan | zal | de zon | morgen | om 6.13 uur | op | komen. | |

| according.to Jan | will | the sun | tomorrow | at 6.13 hour | up | come | ||

| 'According to Jan the sun will rise at 6.13 a.m. tomorrow.' | ||||||||

| b'. | According to John the sun will rise at 6.13 a.m. tomorrow. |

The previous subsection has shown that epistemic modals are used to provide a subjective assessment of the degree of probability that the proposition expressed by the lexical projection of the embedded verb is true. The person providing the assessment will from now on be referred to as the source. Given that the source need not be syntactically expressed by means of an adverbial volgens-PP and need not even be identified by the context, it seems that language users assign specific default values to the source. When uttered "out of the blue", the assessment expressed by epistemic modals in present tense sentences such as (309a) will be attributed to the speaker himself (who, of course, may rely either on his own judgment or on some other source). This default interpretation can only be canceled by explicitly assigning a value to the source by adding a volgens-PP, as in (309b). Observe that it is also possible for speakers to explicitly present themselves as the source.

| a. | Dit huis | moet/kan/zal | instorten. | |

| this house | has.to/may/will | prt.-collapse |

| b. | Volgens Els/mij | moet/kan/zal | dit huis | instorten. | |

| according.to Els/me | has.to/may/will | this house | prt.-collapse |

In past-tense constructions with the universal modal verb moeten'must', the default interpretation of the source again seems to be the speaker. As in the present tense this default interpretation can be canceled or be made explicit by adding a volgens-PP.

| a. | Dit huis | moest | (toen wel) | instorten. | |

| this house | had.to | then prt | prt.-collapse |

| b. | Volgens Els/mij | moest | dit huis | instorten. | |

| according.to Els/me | had.to | this house | prt.-collapse |

We have seen in Subsection I that examples such as (310a) are normally used to indicate that a specific eventuality that occurred before speech time n was inevitable. Furthermore, example (311) shows that it is impossible to cancel the universal quantification expressed by the modal. The reason is that the sources of the first and the second conjunct in (311) have the same value, the speaker. On the assumption that the past-tense interval precedes speech time n, this leads to a contradiction: according to the first conjunct the eventuality occurs in all possible worlds in the past-tense interval, but according to the second conjunct the eventuality did not take place in the actualized part of the present-tense interval.

| $ | Dit huis | moest | (toen wel) | instorten, | maar | het | is | niet | gebeurd. | |

| this house | had.to | then prt | prt.-collapse | but | it | is | not | happened | ||

| 'This house had to collapse, but it didnʼt happen.' | ||||||||||

A potential problem for this account is that the past-tense interval may in principle include speech time n; see the discussion in Section 1.5.1, sub I. Consequently, the first conjunct of (311) should be true if the collapsing of the house takes place after speech time n. This reading of (311) is blocked, however, by Grice's maxim of quantity given that the speaker can more accurately express this situation by means of the present-tense counterpart of (310a): Dit huis moet (wel) instorten'This house has to collapse'.

Examples such as (312) that do explicitly mention the source by means of a volgens-PP are different in that they do not imply that the eventuality denoted by the lexical projection of the embedded main verb occurred before speech time n; this is clear from the fact that examples such as (312a) do not lead to a contradiction but are fully acceptable. The reason is that the sources of the first and the second conjunct have different values: the former has Els as its source and the latter the speaker. This leads to the coherent interpretation that Els' past assessment has proven to be incorrect. In fact, example (312b) may receive a similar interpretation, provided that we construe the pronoun mij as referring to the speaker-in-the-past; by (312b) the speaker asserts that his earlier assessment was wrong. If we interpret the pronoun as referring to the speaker-in-the-present, the example becomes incoherent again.

| a. | Volgens | Els moest | dit huis | instorten, | maar | het | is | niet | gebeurd. | |

| according.to | Els had.to | this house | prt.-collapse | but | it | is | not | happened | ||

| 'According to Els, this house had to collapse, but it didnʼt happen.' | ||||||||||

| b. | Volgens | mij moest | dit huis | instorten, | maar | het | is | niet | gebeurd. | |

| according.to | me had.to | this house | prt.-collapse | but | it | is | not | happened | ||

| 'According to me, this house had to collapse, but it didnʼt happen.' | ||||||||||

In the past-tense example with the existential modal verb kunnen in (313a), the default interpretation of the source is again the speaker; as usual, this default interpretation can be canceled or be made explicit by adding a volgens-PP.

| a. | Dit huis | kon | (elk moment) | instorten. | |

| this house | might | any moment | prt.-collapse | ||

| 'It might have been the case that this house would collapse any moment.' | |||||

| b. | Volgens | Els/mij | kon | dit huis | (elk moment) | instorten. | |

| according.to | Els/me | might | this house | any moment | prt.-collapse |

We have seen in Subsection I that examples such as (313a) are used especially if the event denoted by the lexical projection of the embedded main verb did not yet take place in the actual world, and suggest that certain measures have prevented the eventuality from taking place, that we have had a lucky escape, etc. That the source of this example is the speaker is clear from the fact that adding the conjunct ...maar dat was onzin to this example, as in (314a), leads to an incoherent result: the first conjunct asserts the speaker's currently held belief that there are possible worlds accessible from some point of time in the present-tense interval in which the house would have collapsed (e.g., in which the measures that have prevented the eventuality from occurring in the speaker's actual world were not taken or in which the circumstances were different) and in the second conjunct the speaker characterizes this belief as nonsense. Example (314b), of course, does not suffer from this defect as it is perfectly coherent to characterize a belief held by somebody else or by the speaker-in-the-past as nonsense.

| a. | $ | Dit huis | kon | (elk moment) | instorten, | maar | dat | was | onzin. |

| this house | might | any moment | prt.-collapse | but | that | was | nonsense | ||

| 'It might have been the case that this house would collapse any moment, but that was nonsense.' | |||||||||

| b. | Volgens | Els/mij | kon | dit huis | (elk moment) | instorten, | maar | dat | was onzin. | |

| according.to | Els/me | might | this house | any moment | prt.-collapse | but | that | was nonsense | ||

| 'According to Els/me, it might have been the case that this house would collapse any moment, but that turned out to be nonsense.' | ||||||||||

Given the discussion above, one might expect that in past-tense examples with zullen, the default interpretation of the source is again the speaker, but this is not borne out; such examples typically involve some other source, as will be clear from the fact that the examples in (315) are both fully coherent: (315a) expresses that the prediction of some source has not come true and (315b) expresses that somebody's belief was badly motivated.

| a. | Dit huis | zou | instorten, | maar | het | is | niet | gebeurd. | |

| this house | would | prt.-collapse | but | it | is | not | happened | ||

| 'This house was predicted to collapse, but it didnʼt happen.' | |||||||||

| b. | Dit huis | zou | (elk moment) | instorten, | maar | dat | was onzin. | |

| this house | would | any moment | prt.-collapse | but | that | was nonsense | ||

| 'It was said that this house would collapse any moment, but that was/turned out to be nonsense.' | ||||||||

That past-tense examples with zullen have a default interpretation in which the source is not the speaker may account for the fact that constructions with zullen are versatile in counterfactuals such as (315a) and conditionals such as (316). We will return to constructions of these types in Section 1.5.4.2.

| a. | Als | hij | al zijn geld | in aandelen | belegd | had, | dan | zou | hij | nu | straatarm | zijn. | |

| if | he | all his money | in shares | invested | had, | then | would | he | now | penniless | be | ||

| 'If he had invested all his money in shares, he would be penniless now.' | |||||||||||||

| b. | Als | hij | niet | al zijn geld | in aandelen | belegd | zou hebben, | dan | was hij | nu | schatrijk. | |

| if | he | not | all his money | in shares | invested | would have | then | was he | now | immensely.rich | ||

| 'If he hadnʼt invested all his money in shares, he would be rich now.' | ||||||||||||

The verb zullen thus differs from moeten and kunnen in that the speaker is the default value of the source in the present but not in the past tense. This contrast in interpretation can also be brought to the fore by the contrast between (317) and (318). The fact that the speaker is the default value of the source in present-tense examples with zullen accounts for the fact that examples such as (317) are readily construed as promises made by the speaker as he can be held responsible for the truth of the assertions.

| a. | Ik | zal | u | het boek | deze week | toesturen. | |

| I | will | you | the book | this week | prt.-send | ||

| 'Iʼll send you the book this week.' | |||||||

| b. | Het boek | zal | u | deze week | toegestuurd | worden. | |

| the book | will | you | this week | prt.-sent | be | ||

| 'The book will be sent to you this week.' | |||||||

The fact that the default value of the source in past-tense examples with zullen is some person other than the speaker accounts for the fact that examples such as (318) are construed as promises made by the (implicit) agent of the clause (which, of course, can also be the speaker-in-the-past). Examples such as (318) often have a counterfactual interpretation: they strongly suggest that, to the knowledge of the speaker-in-the-present, the promise has not been fulfilled, which is also clear from the fact that they are typically followed by a conjunct connected with the adversative coordinator maar'but'.

| a. | Els | zou | u/me | het boek | vorige week | toesturen | (maar ...). | |

| Els | would | you/me | the book | last week | prt.-send | but | ||

| 'Els would have sent you/me the book last week (but ...).' | ||||||||

| b. | Het boek | zou | u/me | vorige week | toegestuurd | worden | (maar ...). | |

| the book | would | you/me | last week | prt.-sent | be | but | ||

| 'The book would have been sent to you/me last week (but ...).' | ||||||||

Subsection II has shown that the future reading of the modal verb zullen is triggered by pragmatics and is thus not an inherent part of the meaning of the verb. Present tense sentences with zullen can felicitously refer to the situation depicted in Figure 23 from Subsection I where the split-off point of the possible worlds is situated at speech time n ; such examples cannot refer to a similar situation in which the eventuality k is situated in time interval ia given that such a situation could be more accurately expressed without zullen by means of the present perfect.

If this approach is correct, we would expect future readings to arise as well with other (non-main) verbs in situations like Figure 23. We have already seen in Subsection I, that this is indeed the case with the epistemic modals moeten and kunnen . It is important to stress, however, that we can find the same effect outside the domain of epistemic modal verbs. Consider the examples in (319).

| a. | Ik | ga/kom | vandaag | vissen. | |

| I | go/come | today | fish | ||

| 'I (will) go/come fishing today.' | |||||

| b. | Ik | ga | slapen. | |

| I | go | sleep | ||

| 'I (will) go to sleep.' | ||||

The semantics of the verbs in (319) is rather complex. In some cases, they seem to have maintained the lexical meaning of the main verb and thus imply movement of the subject of the clause: example (319a) with gaan 'to go' may express that the speaker is leaving his default location (e.g., his home) whereas the same example with komen 'to come' may express that the speaker will move to the default location of the addressee; see Section 6.4.1, sub I, for more discussion. However, this change of location reading can also be entirely missing with gaan ; example (319b), for instance, can be uttered when the speaker is already in bed, and thus does not have to change location in order to get to sleep. The verb gaan in (319b) is solely used to express inchoative aspect, a meaning aspect that can also be detected in the examples in (319a); see Haeseryn et al. (1997: Section 5.4.3).

The future reading of the examples in (319) can again be derived by means of Grice's maxim of quantity: if the eventuality denoted by the lexical projection of the main verb had already started at speech time n, the speaker could have described the situation more precisely by using the simple present or the present perfect (depending on whether the eventuality is presented as ongoing or completed). Things are again different in situations where the split-off point of the possible worlds precedes speech time n , like in Figure 22 in Subsection I. Consider the examples in (320) and suppose that the speaker does not know anything about Els' movement since some contextually determined moment preceding speech time n.

| a. | Els gaat | vandaag | vissen. | |

| Els goes | today | fish | ||

| 'Els goes fishing today.' | ||||

| b. | Els komt | vandaag | vissen. | |

| Els comes | today | fish | ||

| 'Els will come fishing today.' | ||||

In the situation sketched, example (320a) does not imply anything about the temporal location of the eventuality denoted by the lexical projection of the main verb within the present-tense interval; it may precede, overlap with or follow speech time n . In (320b), a future reading is greatly favored given that this example strongly suggests that the agent of the clause is moving to the default location of the speaker; if Els had already joined the speaker, the speaker could have expressed the situation more precisely by using the present perfect: Els is vandaag komen vissen'Els has come fishing today'.

To conclude, note that we find similar facts with the verb blijven , which in its main verb use means "to stay" and denotes lack of movement. In examples such as (321a) the meaning of the main verb is retained, and the sentence is interpreted as referring to a future event. In examples such as (321b) the locational interpretation has completely disappeared and it is just a durative (non-terminative) aspect that remains, and the eventuality denoted by the lexical projection of the main verb is therefore construed as occurring at speech time n.

| a. | Jan blijft | eten. | |

| Jan stays | eat | ||

| 'Jan will stay for dinner.' | |||

| b. | Jan blijft twijfelen. | |

| Jan stays doubt | ||

| 'Jan continues to doubt.' |