- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

The main part of this section consists of developing a partly novel classification of main verbs based on the number and the type of arguments they take. Before we take up this issue in Subsection II, we will briefly introduce a number of basic notions and conventions that will be used in the discussion.

Like all lexical items, verbs have unpredictable properties (like the Saussurean arbitrary form-meaning pairing) that are listed in the mental lexicon. Among these properties there are also properties relevant to syntax, like the number of arguments selected by the verb and the form these arguments take. Although Section 1.2.4 will show that some of these properties are closely related to the meanings of the verbs in question and that it therefore remains to be seen whether these properties are semantic or syntactic in nature, we will introduce in this subsection a number of notions and conventions that are used in the syntactic literature (including this grammar) to refer to these properties.

Main verbs are normally syntactically classified on the basis of the number and the kind of arguments they take. These properties are sometimes formalized by assigning main verbs subcategorization frames, which specify the number of arguments as well as the categories (e.g., NP or PP) and the thematic roles of these arguments: an intransitive verb like lachen 'to laugh' has one nominal argument with the thematic role of agent; a transitive verb like lezen 'to read' has two nominal arguments with the thematic roles of, respectively, agent and theme; a ditransitive verb like geven 'to give' has three nominal arguments with the thematic roles of agent, theme and recipient; we will return to the fact that the recipient of geven can also be expressed as a PP in Subsection D below.

| a. | lopenV: NPAgent | |

| walk |

| a'. | Jan loopt. | |

| Jan walks |

| b. | lezenV: NPAgent, NPTheme | |

| read |

| b'. | Marie leest | een krant. | |

| Marie reads | a newspaper |

| c. | gevenV: NPAgent, NPTheme, PPRecipient | |

| give |

| c'. | Jan geeft | een boek | aan Marie. | |

| Jan gives | a book | to Marie |

At least some of the information in these subcategorization frames is systematically related to the meanings of the verbs in question. This is evident from the fact that the arguments mentioned in (23) fill slots in the semantic predicate frames implied by the verbs: lachen is a one-place predicate lachen (x) and the agentive argument fills the single argument slot; lezen is a two-place predicate and the agent and the theme argument fill, respectively, the x and the y slot in the predicate frame lezen (x,y); geven is a three-place predicate and again the three arguments fill the slots in the predicate frame geven (x,y,z).

The arguments that fill the slots in the predicate frames of two- and three-place predicates are not all on an equal footing: filling the y and z slots in a sense creates one-place predicates, which can be predicated of the arguments placed in the x slot. If we rephrase this in syntactic terms, we can say that fillers of y and/or z correspond to the objects of the clause, and that fillers of x correspond to subjects. Since addition of the object(s) to the verb creates a predicate in the traditional, Aristotelian sense, the objects are often referred to as the complements or internal arguments of the verb, subjects, on the other hand, are the arguments that these one-place predicate are predicated of and they are therefore also referred to as external arguments of the verb. In (24), the subcategorization frames in (23) are repeated with the external arguments underlined in order to distinguish them from the internal arguments.

| a. | lopenV: NPAgent | |

| walk |

| a'. | Jan | [loopt]Pred | |

| Jan | walks |

| b. | lezenV: NPAgent, NPTheme | |

| read |

| b'. | Marie | [leest | een krant]Pred | |

| Marie | reads | a newspaper |

| c. | gevenV: NPAgent, NPTheme, NPrecipient | |

| give |

| c'. | Jan [geeft | een boek | aan Marie]Pred | |

| Jan gives | a book | to Marie |

There are several complications that are not discussed here, subsection II, for example, will show that so-called unaccusative and undative verbs do not have an external argument but are predicated of an internal argument; cf. Table 2 below.

The fact that the three arguments selected by a verb like geven'to give' function as, respectively, an agent, a theme and a recipient is often referred to as semantic selection. Semantic selection may, however, be much more specific than that; verbs like zich verzamelen'to gather', zich verspreiden'to spread' and omsingelen'to surround' in (25), for example, normally require their subject to be plural when headed by a count noun unless the noun denotes a collection of entities like menigte'crowd'.

| a. | De studenten | verspreiden | zich. | |

| the students | spread | refl |

| a'. | De menigte/*student | verspreidt | zich. | |

| the crowd/student | spread | refl |

| b. | De studenten | omsingelen | het gebouw. | |

| the students | surround | the building |

| b'. | De menigte/*student | omsingelt | het gebouw. | |

| the crowd/student | surrounds | the building |

There are also verbs like verzamelen'to collect' and (op)stapelen'to stack/pile up' that impose similar selection restrictions on their objects: the object of such verbs can be a plural noun phrase or a singular noun phrase headed by a count noun denoting collections of entities, but not a singular noun phrase headed by a count noun denoting discrete entities.

| a. | Jan verzamelt | gouden munten. | |

| Jan collects | golden coins | ||

| 'Jan is collecting golden coins.' | |||

| a'. | Jan verzamelt | porselein/*een gouden munt. | |

| Jan collects | china/a golden coin | ||

| 'Jan is collecting china.' | |||

| b. | Jan stapelt | de borden | op. | |

| Jan piles | the plates | up | ||

| 'Jan is piling up the plates.' | ||||

| b'. | Jan stapelt | het servies/*het bord | op. | |

| Jan piles | the dinnerware/the plate | up | ||

| 'Jan is piling up the dinnerware.' | ||||

The examples in (27) show that the information may be of an even more idiosyncratic nature: verbs of animal sound emissions often select an external argument that refers to a specific or at least very small set of animal species, verbs that take an agentive external argument normally require their subject to be animate, and verbs of consumption normally require their object to be edible, drinkable, etc.

| a. | Honden, vossen en reeën | blaffen, | ganzen gakken | en | paarden | hinniken. | |

| dogs, foxes and roe deer | bark, | geese honk | and | horses | neigh |

| b. | Jan/$de auto | eet | spaghetti. | |

| Jan/the car | eats | spaghetti | ||

| 'Jan is eating spaghetti.' | ||||

| c. | Jan eet | spaghetti/$staal. | |

| Jan eats | spaghetti/steel | ||

| 'Jan is eating spaghetti/steel.' | |||

Given that restrictions of the kind illustrated in (25) through (27) do not enter into the verb classifications that we will discuss here, we need not delve into the question as to whether such semantic selection restrictions must be encoded in the subcategorization frames of the verbs or whether they follow from our knowledge of the world and/or our understanding of the meaning of the verb in question; see Grimshaw (1979) and Pesetsky (1991) for related discussion.

Subcategorization frames normally provide information about the categories of the arguments, that is, about whether they must be realized as a noun phrase, a prepositional phrase, a clause, etc. That this is needed can be motivated by the fact that languages may have different subcategorization frames for similar verbs; the fact that the Dutch verb houden requires a PP-complement whereas the English verb to like takes a direct object shows that the category of the internal argument(s) cannot immediately be inferred from the meaning of the verb but may be a language-specific matter.

| a. | houdenV: NPExperiencer, [PP van NPTheme] |

| a'. | Jan houdt van spaghetti. |

| b. | likeV: NPExperiencer, NPTheme |

| b'. | John likes spaghetti. |

That the category of the internal argument(s) cannot immediately be inferred from the meaning of the verb is also suggested by the fact that verbs like verafschuwen'to loathe', walgen'to loathe', which express more or less similar meanings, do have different subcategorization frames.

| a. | JanExperiencer | verafschuwt | spaghettiTheme. | NP-complement | |

| Jan | loathes | spaghetti |

| b. | JanExperiencer | walgt van | spaghettiTheme. | PP-complement | |

| Jan | loathes | spaghetti |

Furthermore, subcategorization frames must provide more specific information about, e.g., the prepositions that head PP-complements. This can again be motivated by comparing some Dutch and English examples; although the Dutch translation of the English preposition for provided by dictionaries is voor, the examples in (30) show that in many (if not most) cases English for in PP-complements does not appear as voor in the Dutch renderings of these examples, and, vice versa, that Dutch voor often has a counterpart different from for. This again shows that the choice of preposition is an idiosyncratic property of the verb, which cannot be inferred from the meaning of the clause.

| a. | hopen op NP |

| a'. | to hope for NP |

| b. | verlangen naar NP |

| b'. | to long for NP |

| c. | behoeden voor NP |

| c'. | to guard from |

| d. | zwichten voor NP |

| d'. | to knuckle under NP |

The above, of course, does not imply that the choice between nominal and PP-complements is completely random. There are certainly a number of systematic correlations between the semantics of the verb and the category of its internal arguments; cf. Section 1.2.4. The examples in (31), for instance, show that incremental themes (themes that refer to entities that gradually come into existence as the result of the event denoted by the verb) are typically realized as noun phrases, whereas themes that exist independently of the event denoted by the verb often appear as PP-complements.

| a. | Jan schreef | gisteren | een gedicht. | |

| Jan wrote | yesterday | a poem | ||

| 'Jan wrote a poem yesterday.' | ||||

| b. | Jan schreef | gisteren | over de oorlog. | |

| Jan wrote | yesterday | about the war | ||

| 'Jan wrote about the war yesterday.' | ||||

Similarly, affected themes are normally realized as direct objects, whereas themes that are not (necessarily) affected by the event can often be realized as PP-complements. Example (32a), for instance, implies that Jan hit the hare, whereas (32b) does not have such an implication; cf. Section 3.3.2, sub I.

| a. | Jan schoot | de haas. | |

| Jan shot/hit | the hare |

| b. | Jan schoot | op de haas. | |

| Jan shot | at the hare |

The same thing holds for the choice between a nominal and a clausal complement. The examples in (33), for instance, show that verbs like zeggen'to say' or denken'to think', which select a proposition as their complement, typically take declarative clauses and not noun phrases as their complement, since the former but not the latter are the canonical expression of propositions.

| a. | Jan zei/dacht | dat | zwanen | altijd | wit | zijn. | |

| Jan said thought | that | swans | always | white | are | ||

| 'Jan said/thought that swans are always white.' | |||||||

| b. | * | Jan zei/dacht | het verhaal. |

| Jan said/thought | the story |

The examples in (34) show that something similar holds for verbs like vragen or zich afvragen, which typically select a question.

| a. | Jan vroeg/vroeg | zich | af | of | zwanen | altijd | wit | zijn. | |

| Jan asked/wondered | refl | prt. | whether | swans | always | white | are | ||

| 'Jan asked/wondered whether swans are always white.' | |||||||||

| b. | * | Jan vroeg het probleem/vroeg | zich | het probleem | af. |

| Jan asked the problem/wondered | refl | the problem | prt. |

Finally, it can be noted that the choice for a specific preposition as the head of a PP-complement need not be entirely idiosyncratic either; there are several subregularities (Loonen 2003) and in some cases the (original) locational meaning of the preposition used in PP-complements of the verb can still be recognized; see Schermer-Vermeer (2006). Two examples are volgen uit'to follow from' and zondigen tegen'to sin against'.

Some verbs can occur in more than one "verb frame"; cf. the examples in (31) and (32). A familiar example of such verb frame alternations is given in (35), which shows that verbs like schenken'to give/present' can realize their internal recipient argument either as a noun phrase or as an aan-PP.

| a. | Peter schenkt | het museumRec | zijn verzamelingTheme. | |

| Peter gives | the museum | his collection |

| b. | Peter schenkt | zijn verzamelingTheme | aan het museumRec. | |

| Peter gives | his collection | to the museum |

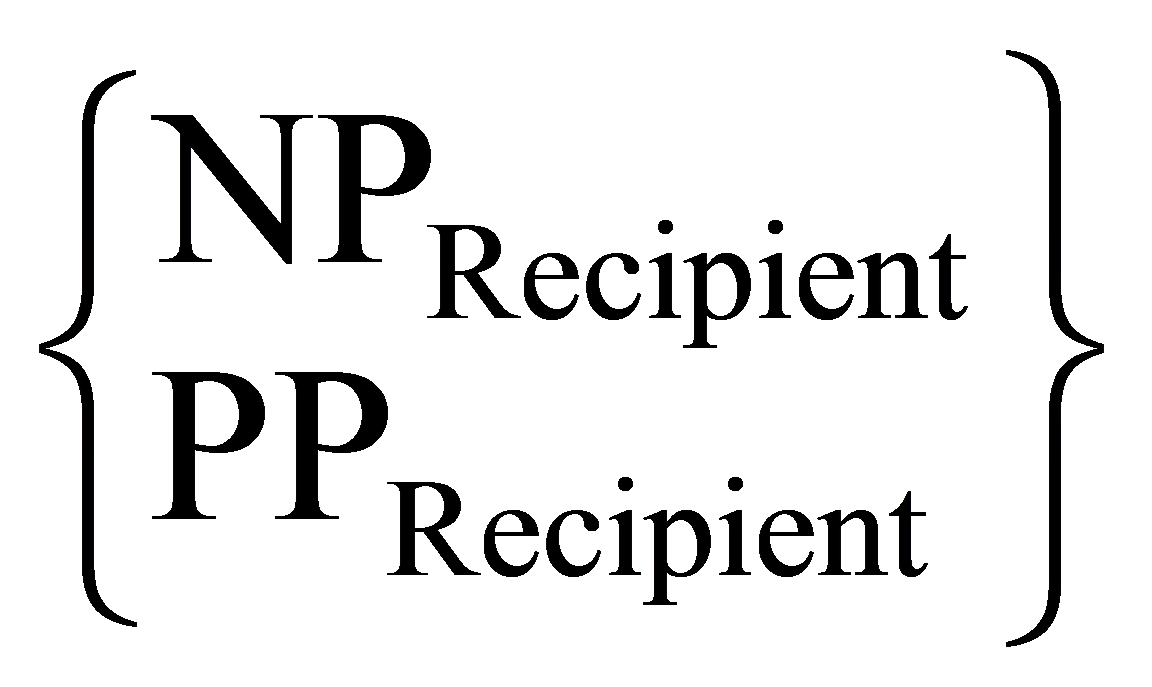

In early generative grammar this alternation was accounted for by assuming that the subcategorization frame of the verb schenken was as in (36), in which the braces indicate that the NP and PP are alternative realizations of the recipient argument.

| schenkenV: NPAgent, NPTheme, |  |

There are, however, alternative ways of accounting for this alternation. One way is to derive example (35a) from (35b) by means of a transformation normally referred to as dative shift; see Emonds (1972/1976) and many others. Another way is to assume that there is just a single underlying semantic representation but that the syntactic mapping of the arguments may vary. We refer the reader to Levin & Rappaport Hovav (2005:ch.7) for a review of these and other theoretical approaches to verb frame alternations, and to Chapter 3 for an extensive discussion of the verb frame alternations that can be found in Dutch.

This subsection takes the traditional classification of main verbs as its starting point, which is based on the adicity (or valency) of these verbs, that is, the number of nominal arguments they take: intransitive verbs have a subject but do not select any object, transitive verbs select an additional direct object, and ditransitive verbs select a direct and an indirect object. We will show, however, that this classification is inadequate and that a better way of classifying verbs is by also appealing to the semantic roles that they assign to their nominal arguments.

Traditional grammar normally classifies main verbs on the basis of the adicity of these verbs, that is, the number of nominal arguments they take. For reasons that will become clear in what follows, we will use the notions given in (37) to refer to the three subclasses traditionally distinguished and reserve the traditional notions of intransitive, transitive and ditransitive verbs to refer to specific subsets of these classes.

| a. | Monadic verbs: lachen'to laugh', arriveren'to arrive' |

| b. | Dyadic verbs: eten'to eat', bevallen'to please' |

| c. | Triadic verbs: geven'to give', aanbieden'to offer' |

The classification of main verbs in (37) is crucially based on the notions of subject and object. This has been criticized by pointing out that in this way verbs are lumped together with quite different properties; see the discussion in Subsection B. This is due to the fact that whether an argument is realized as a subject or an object is determined by the syntactic properties of the construction as a whole and not by the semantic function of the arguments. This can be readily illustrated by means of the active/passive pair in (38): in (38a), the subject de bij'the bee' is an external argument, which is clear from the fact that it has the prototypical subject role of agent, whereas in (38b) the subject de kat'the cat' is an internal argument, as is clear from the fact that it has the prototypical direct object role of patient.

| a. | De bij | stak | de kat. | |

| the bee | stung | the cat |

| b. | De kat | werd | (door de bij) | gestoken. | |

| the cat | was | by the bee | stung |

In generative grammar, the semantic difference between the subjects of the examples in (38) is often expressed by saying that the subject de bij'the bee' in (38a) is a "logical" subject, whereas the subject de kat in (38b) is a "derived" subject. We will from now on refer to the derived subjects as DO-subjects, since the discussion of the examples in (40) and (42) in Subsection B will show that such derived subjects originate in the same structural position in the clause as direct objects.

Perlmutter (1978) and Burzio (1986) have shown that the set of monadic verbs in (37a) can be divided into two distinct subclasses. Besides run-of-the-mill intransitive verbs like lachen'to laugh', there is a class of so-called unaccusative verbs like arriveren'to arrive' with a number of distinctive properties (which may differ from language to language). The examples in (39) illustrate some of the differences between the two types of monadic verbs that are normally given as typical for Dutch; cf. Hoekstra (1984a).

| a. | Jan heeft/*is | gelachen. | |

| Jan has/is | laughed |

| a'. | Jan is/*heeft | gearriveerd. | |

| Jan is/has | arrived |

| b. | * | de | gelachen | jongen |

| the | laughed | boy |

| b'. | de | gearriveerde | jongen | |

| the | arrived | boy |

| c. | Er | werd | gelachen. | |

| there | was | laughed |

| c'. | * | Er | werd | gearriveerd. |

| there | was | arrived |

The first property involves auxiliary selection in the perfect tense: the (a)-examples show that intransitive verbs like lachen take the perfect auxiliary hebben'to have', whereas unaccusative verbs like arriveren take the auxiliary zijn'to be'. The second property involves the attributive use of past/passive participles: the (b)-examples show that past/passive participles of unaccusative verbs can be used attributively to modify a head noun that corresponds to the subject of the verbal construction, whereas past/passive participles of intransitive verbs lack this ability. The third property involves impersonal passivization: the (c)-examples show that this is possible with intransitive but not with unaccusative verbs.

Like monadic verbs, dyadic verbs can be divided into two distinct subclasses. Besides run-of-the-mill transitive verbs like kussen'to kiss' with an accusative object, we find so-called nom-dat verbs like bevallen'to please' taking a dative object; since Dutch has no morphological case, we illustrate the case property of the nom-dat verbs by means of the German verb gefallen'to please' in (40a'). Lenerz (1977) and Den Besten (1985) have shown that these nom-dat verbs are special in that the subject follows the object in the unmarked case, as in the (b)-examples.

| a. | Dutch: | dat | jouw verhalen | mijn broer | niet | bevallen. |

| a'. | German: | dass | deine Geschichtennom | meinem Bruderdat | nicht | gefallen. | |

| literal: | that | your stories | my brother | not | please | ||

| 'that your stories donʼt please my brother.' | |||||||

| b. | Dutch: | dat | mijn broer | jouw verhalen | niet | bevallen. |

| b'. | German: | dass | meinem Bruderdat | deine Geschichtennom | nicht | gefallen. | |

| literal: | that | my brother | your stories | not | please | ||

| 'that your stories donʼt please my brother.' | |||||||

This word order property readily distinguishes nom-dat verbs from transitive verbs since the latter do not allow the subject after the object; transitive constructions normally have a strict nom-acc order (unless the object undergoes wh-movement or topicalization).

| a. | dat | mijn broernom | jouw verhalenacc | leest. | |

| that | my brother | your stories | reads | ||

| 'that my brother is reading your stories.' | |||||

| b. | * | dat jouw verhalenacc mijn broernom leest. |

The (b)-examples in (42) show that the same word order variation as with nom-dat verbs is found with passivized ditransitive verbs, in which case the dat-nom order is again the unmarked one.

| a. | Jannom | bood | de meisjesdat | de krantacc | aan. | |

| Jan | offered | the girls | the newspaper | prt. | ||

| 'Jan offered the girls the newspaper.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | de meisjesdat | de krantnom | aangeboden | werd. | |

| that | the girls | the newspaper | prt.-offered | was | ||

| 'that the newspaper was offered to the girls.' | ||||||

| b'. | dat | de krantnom | de meisjesdat | aangeboden | werd. | |

| that | the newspaper | the girls | prt.-offered | was | ||

| 'that the newspaper was offered to the girls.' | ||||||

Den Besten (1985) analyzes the word order variation in these examples by assuming that the DO-subject originates in the regular direct object position and optionally moves into subject position; see the representations in (43), in which the em-dash indicates the empty subject position of the clause and the trace the original position of the nominative phrase. Broekhuis (1992/2008) has shown that this movement is not really optional but subject to conditions related to the information structure of the clause; the subject remains in its original position if it is part of the focus (new information) of the clause but moves into the regular subject position if it is part of the presupposition (old information) of the clause.

| a. | dat-nom order: [dat — IO DO-subject V] |

| b. | nom-dat order: [dat DO-subject IO ti V] |

The word order similarities between (40) and (42) show that nom-dat verbs also take DO-subjects; the dat-nom orders in the (b)-examples in (40) are the base-generated ones and the nom-dat orders in the (a)-examples are derived by movement of the DO-subject into the regular subject position of the clause.

Monadic unaccusative verbs like arriveren'to arrive' are like nom-dat verbs in that they take a DO-subject. This can be illustrated by means of the examples in (44). The (b)-examples show that the past/passive participle of a transitive verb like kopen'to buy' can be used as an attributive modifier of a noun that corresponds to the internal theme argument (here: direct object) of the verb, but not to the external argument (subject) of the verb.

| a. | Het meisje | kocht | het boek. | |

| the girl | bought | the book |

| b. | het | gekochte | boek | |

| the | bought | book |

| b'. | * | het gekochte | meisje |

| the bought | girl |

The fact that the past participle of arriveren in (39b') can be used as an attributive modifier of a noun that corresponds to the subject of the verb therefore provides strong evidence in favor of the claim that the subject of an unaccusative verb is also an internal theme argument of the verb. That subjects of unaccusative verbs are not assigned the prototypical semantic role of external arguments (= agent) can furthermore be supported by the fact that unaccusative verbs never allow agentive er-nominalization, that is, they cannot be used as the input of the derivational process that derives person nouns by means of the suffix -er; the primed examples in (45) show that whereas many subjects of intransitive and (di-)transitive verbs can undergo this process, unaccusative and nom-dat verbs never do. See N1.3.1.5 and N2.2.3.1 for a more detailed discussion of agentive er-nominalization.

| a. | snurken | 'to snore' |

| a'. | snurker | 'snorer' | intransitive |

| b. | arriveren | 'to arrive' |

| b'. | *arriveerder | 'arriver' | unaccusative |

| c. | kopen | 'to buy' |

| c'. | koper | 'buyer' | transitive |

| d. | bevallen | 'to please' |

| d'. | *bevaller | 'pleaser' | nom-dat |

| e. | aanbieden | 'to offer' |

| e'. | aanbieder | 'provider' | ditransitive |

We will discuss here one final argument for claiming that subjects of unaccusative verbs are internal arguments. This is provided by causative-inchoative pairs such as (46), which show that the subject of the unaccusative construction in (46b) stands in a similar semantic relation with the (inchoative) verb breken as the direct object of the corresponding transitive construction with the (causative) verb breken in (46a); cf. Mulder (1992), Levin (1993) and Levin & Rappaport Hovav (1995:ch.2).

| a. | Jan | heeft | het raam | gebroken. | |

| Jan | has | the window | broken | ||

| 'Jan has broken the window.' | |||||

| b. | Het raam | is gebroken. | |

| the window | is broken | ||

| 'The window has broken.' | |||

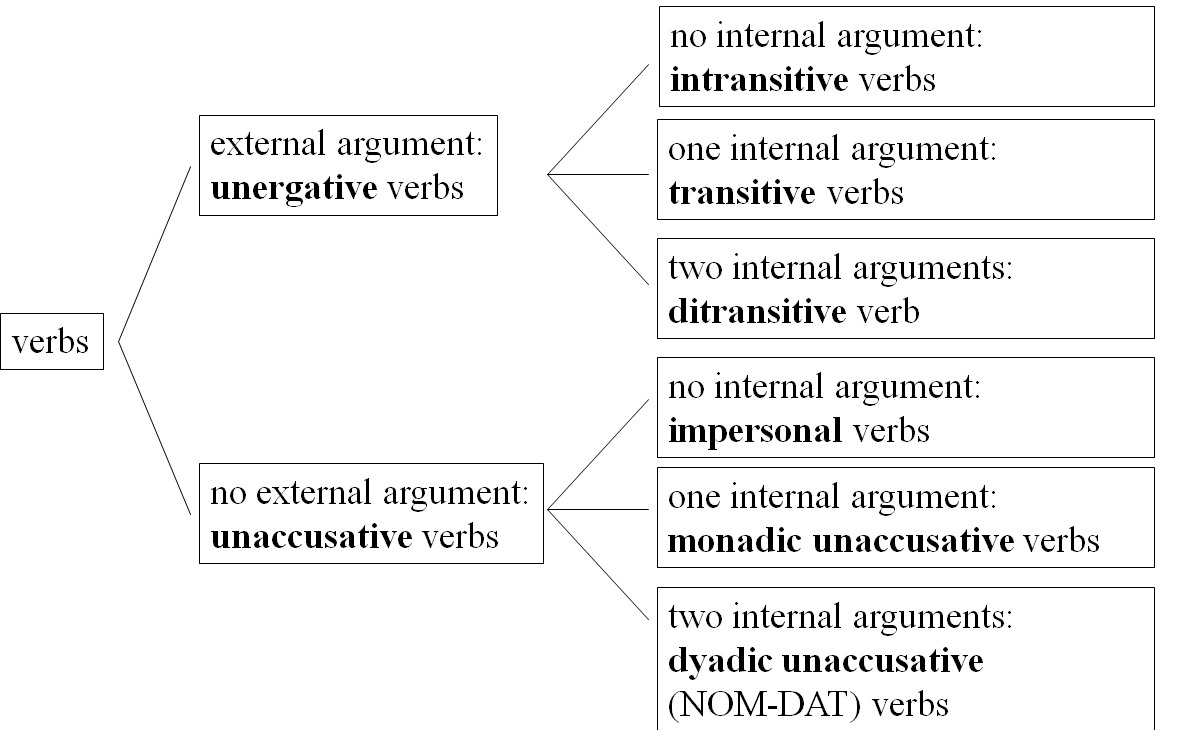

The discussion in the previous subsections has shown that the traditional classification of main verbs on the basis of the number of nominal arguments that they take is seriously flawed. The set of monadic verbs lumps together two sets of verbs with very distinct properties, and the same thing holds for the set of dyadic verbs. When we also take into account impersonal verbs like sneeuwen'to snow' which are often assumed not to take any argument at all and occur with the non-referential subject het'it', we may replace the traditional classification by the more fine-grained one in Table 2, which appeals to the type of argument(s) the verb takes, that is, the distinction between internal and external arguments.

| name | external argument | internal argument(s) | |

| no internal argument | intransitive: snurken 'to snore' | nominative (agent) | — |

| impersonal: sneeuwen 'to snow' | — | — | |

| one internal argument | transitive: kopen 'to buy' | nominative (agent) | accusative (theme) |

| unaccusative: arriveren 'to arrive' | — | nominative (theme) | |

| two internal arguments | ditransitive: aanbieden 'to offer' | nominative (agent) | dative (goal) accusative (theme) |

| nom-dat verb: bevallen 'to please' | — | dative (experiencer) nominative (theme) | |

| ???? | — | nominative (goal) accusative (theme) |

Figure 2 gives the same classification in the form of a graph. In this figure it can be seen that the unaccusative verbs form the counterpart of the so-called unergative verbs (for which reason the unaccusative verbs are also known as ergative verbs in the literature). This graph nicely expresses our claim that the distinction between unaccusative and unergative verbs is more basic than that based on the adicity of the verb.

Observe that we also indicated in Table 2 the prototypical semantic roles assigned to the arguments in question without intending to exclude the availability of other semantic roles; external arguments, for example, need not be agents but can also function as external causes, as is clearly the case when the human subject in (46a) is replaced by a non-human one like de storm'the tempest': De storm brak het raam'The storm broke the window'.

The classification in Table 2 contains one logical possibility that we have not yet discussed, in which an internal goal argument (that is, an argument with a semantic role similar to that assigned to the dative argument of a ditransitive verb) functions as the subject of the clause, and which we may therefore call undative verbs. The current linguistic literature normally does not recognize that verbs of this type may exist, for which reason we marked this option with question marks in the table, but this subsection argues that they do exist and that the prototypical instantiations of this type are the verbs hebben'to have', krijgen'to get', and houden'to keep'. This subsection shows this only for the verb krijgen; hebben and houden as well as a number of other potential cases will be discussed in Section 2.1.4.

Consider the examples in (47). It seems that the indirect object in (47a) and the subject in (47b) have a similar semantic role: they both seem to function as the recipient/goal of the theme argument het boek'the book'. The fact that the subject in (47b) is not assigned the prototypical subject role of agent/cause furthermore suggests that the verb krijgen'to get' does not have an external argument (although the agent/cause can be expressed in a van-PP). Taken together, these two facts suggest that the noun phrase Marie in (47b) is not an underlying but a derived IO-subject. The remainder of this subsection will show that there are a number of empirical facts supporting this claim.

| a. | Jan | gaf | Marie het boek. | |

| Jan | gave | Marie the book |

| b. | Marie | kreeg | het boek | (van Jan). | |

| Marie | got | the book | of Jan | ||

| 'Marie got the book from Jan.' | |||||

Example (45) in Subsection B has shown that er-nominalization is only possible if an external (agentive) argument is present; snurker (snore + -er) versus *arriveerder (arrive + -er). If the subject in (47b) is indeed an internal goal argument, we expect er-nominalization of krijgen to be impossible as well. Example (48a) shows that this prediction is indeed borne out (krijger only occurs with the meaning "warrior"; this noun was derived from medieval crigen, which was also the input verb for gecrigen, which eventually developed into modern krijgen; cf. Landsbergen 2009:ch.4). The discussion in Subsection B has further shown that unaccusative verbs cannot be passivized, which strongly suggests that the presence of an external argument is a necessary condition for passivization. If so, we correctly predict passivization of (47b) also to be impossible; cf. example (48b).

| a. | * | de krijger | van dit boek |

| the get-er | of this book |

| b. | * | Het boek | werd/is | (door Marie) | gekregen. |

| the book | was/has.been | by Marie | gotten |

Although the facts in (48) are certainly suggestive, they are of course not conclusive for arguing that krijgen is an undative verb, since we know that not all verbs with an external argument allow er-nominalization, and that there are several additional restrictions on passivization. There is, however, more evidence that supports the idea that the subject of krijgen is a derived subject. For example, the claim that krijgen has an IO-subject may account for the fact that the Standard Dutch example in (49a), which contains the idiomatic double object construction iemand de koude rillingen bezorgen'to give someone the creeps', has the counterpart in (49b) with krijgen.

| a. | De heks | bezorgde | Jan de koude rillingen. | |

| the witch | gave | Jan the cold shivers | ||

| 'The witch gave him the creeps.' | ||||

| b. | Jan kreeg | de koude rillingen | (van de heks). | |

| Jan got | the cold shivers | from the witch | ||

| 'Jan has gotten the creeps from the witch.' | ||||

The final and perhaps most convincing argument in favor of the assumption that krijgen has a derived subject is that it is possible to have the possessive constructions in (50). If a locative PP is present, the possessor of the complement of the preposition can be realized as a dative noun phrase; the object Marie in (50a) must be construed as the possessor of the noun phrase de vingers. Generally speaking, it is only the possessive dative that can perform the function of possessor. The subject of the verb krijgen, however, is an exception to this general rule; the subject Marie in (50b) is also interpreted as the possessor of the noun phrase de vingers. This could be accounted for by assuming that Marie is not an external argument in (50b), but an internal argument with the same function as Marie in (50a).

| a. | Jan | gaf | Marie | een tik op de vingers. | |

| Jan | gave | Marie | a slap on the fingers |

| b. | Marie | kreeg | een tik | op de vingers. | |

| Marie | got | a slap | on the fingers |

This section has shown that the traditional distinction between monadic, dyadic and triadic verbs lumps together verbs with quite distinct properties: the intransitive and unaccusative verbs, for example, do not have more in common than that they take only one nominal argument.

| a. | Verbs with an adicity of zero: impersonal verbs. |

| b. | Monadic verbs (adicity of one): intransitive and unaccusative verbs. |

| c. | Dyadic verbs (adicity of two): transitive and nom-dat verbs. |

| d. | Triadic verbs (adicity of three): ditransitive verbs. |

This suggests that the traditional classification must be replaced by a classification that also appeals to the type of argument(s) the verb takes, that is, the distinction between internal and external arguments. This leads to the more fine-grained classification in Table 3. Recall from the discussion of Table 2 that the table also indicates the prototypical semantic roles assigned to the arguments in question without intending to exclude the availability of other semantic roles.

| name used in this grammar | external argument | internal argument(s) | |

| no internal argument | intransitive: snurken 'to snore' | nominative (agent) | — |

| impersonal: sneeuwen 'to snow' | — | — | |

| one internal argument | transitive: kopen 'to buy' | nominative (agent) | accusative (theme) |

| unaccusative: arriveren 'to arrive' | — | nominative (theme) | |

| two internal arguments | ditransitive: aanbieden 'to offer' | nominative (agent) | dative (goal) accusative (theme) |

| nom-dat verb: bevallen 'to please' | — | dative (experiencer) nominative (theme) | |

| undative: krijgen 'to get'; hebben 'to have'; houden 'to keep' | — | nominative (goal) accusative (theme) |

- 1985The ergative hypothesis and free word order in Dutch and GermanToman, Jindřich (ed.)Studies in German GrammarDordrecht/CinnaminsonForis Publications23-65

- 1985The ergative hypothesis and free word order in Dutch and GermanToman, Jindřich (ed.)Studies in German GrammarDordrecht/CinnaminsonForis Publications23-65

- 1992Chain-government: issues in Dutch syntaxThe Hague, Holland Academic GraphicsUniversity of Amsterdam/HILThesis

- 2008Derivations and evaluations: object shift in the Germanic languagesnullStudies in Generative GrammarBerlin/New YorkMouton de Gruyter

- 1986Italian syntax: a government-binding approachnullnullDordrecht/Boston/Lancaster/TokyoReidel

- 1972Evidence that indirect object movement is a structure preserving ruleFoundations of Language8546-561

- 1976A transformational approach to English syntax: root, structure-preserving, and local transformationsnullnullNew YorkAcademic Press

- 1979Complement selection and the lexiconLinguistic Inquiry10279-326

- 1984Transitivity. Grammatical relations in government-binding theorynullnullDordrecht/CinnaminsonForis Publications

- 2009Cultural evolutionary modeling of patterns in language change. Exercises in evolutionary linguisticsUniversity of LeidenThesis

- 1977Zur Abfolge nominaler Satzglieder im DeutschennullStudien zur deutschen GrammatikTübingenNarr

- 1993English verb classes and alternationsnullnullChicago/LondonUniversity of Chicago Press

- 1995Unaccusativity at the syntax-lexical semantics interfacenullnullCambridge, MA/LondonMIT Press

- 2005Argument realizationnullnullCambridge/New YorkCambridge University Press

- 2003Stante pede gaande van dichtbij langs AF bestemming @University of UtrechtThesis

- 1992The aspectual nature of syntactic complementationLeidenUniversity of LeidenThesis

- 1978Impersonal passives and the unaccusative hypothesisBerkeley Linguistics Society4157-189

- 1991Zero syntax II: infinitives

- 2006Worstelen met het voorzetselvoorwerpNederlandse Taalkunde11146-167