- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

Weak (phonetically reduced) proforms normally occur in the left periphery of the middle field of the clause, with the exception of weak subject pronouns, which may also occur in clause-initial position; cf. Section 9.3. We can distinguish the three groups of weak elements in (173), all of which have strong counterparts with the exception of expletive and partitive er.

| a. | Referential personal pronouns; ie/ze'he/she', ʼm/ʼr'him/her', etc. |

| b. | Reflexive personal pronouns: me'myself', je'yourself', zich'him/herself', etc. |

| c. | the R-word er: expletive, locational, prepositional and quantitative |

The set of elements in (173) closely resembles the set of clitics found in French: see the lemma French personal pronouns at Wikipedia for a brief review. We will see that the relative order of the weak proforms also exhibits a number of similarities with the French clitics, which may justify the claim that the Dutch weak proforms are clitics as well; see Huybregts (1991), Zwart (1993/1996) as well as Haegeman (1993a/1993b) on W-Flemish. It should be noted, however, that the Dutch proforms differ from French clitics in that they do not need a verbal host: while the French clitics always cluster around a main or an auxiliary verb, the Dutch proforms do not require this. In order to not bias the discussion beforehand, we will refer to the movement that places weak proforms in the left periphery of the middle field as weak proform shift. Subsection I starts with a discussion of the weak referential personal pronouns, Subsection II discusses the weak (simplex) reflexive pronouns, and Subsection III concludes with the various uses of the weak R-word er.

Table 2 shows the classification of referential personal pronouns, which is more extensively discussed in Section N5.2.1. The discussion in this subsection focuses on the distribution of the weak forms.

| singular | plural | ||||||||

| subject | object | subject | object | ||||||

| strong | weak | strong | weak | strong | weak | strong | weak | ||

| 1st person | ik | ’k | mij | me | wij | we | ons | — | |

| 2nd person | regular | jij | je | jou | je | jullie | — | jullie | — |

| polite | u | u | u | u | |||||

| 3rd person | masculine | hij | -ie | hem | ’m | zij | ze | henacc hundat | ze |

| feminine | zij | ze | haar | (d)’r | |||||

| neuter | ?het | ’t | *?het | ’t | |||||

In embedded clauses weak subject pronouns are right-adjacent to the complementizer (if present), and immediately precede or follow the finite verb in second position in main clauses; cf. Paardekooper (1961). This is illustrated in (174) by means of the 3rd person singular feminine pronoun ze'her'.

| a. | dat | ze | waarschijnlijk | morgen | komt. | embedded clause | |

| that | she | probably | tomorrow | comes | |||

| 'that sheʼs probably coming tomorrow.' | |||||||

| b. | Ze | komt | waarschijnlijk | morgen. | subject-initial main clause | |

| she | comes | probably | tomorrow | |||

| 'Sheʼs probably coming tomorrow.' | ||||||

| b'. | Waarschijnlijk | komt | ze | morgen. | other main clauses | |

| probably | comes | she | tomorrow | |||

| 'Probably sheʼs coming tomorrow.' | ||||||

The examples in (175) show that subject pronouns can occur in positions more to the right only if they are strong and carry contrastive focus accent. The question mark in example (175b) is used to indicate that even then strengthening of the pronoun by means of a focus particle is often preferred.

| a. | * | dat | waarschijnlijk | ze | morgen | komt. |

| that | probably | she | tomorrow | comes |

| b. | dat | waarschijnlijk | ?(zelfs) zij | morgen | komt. | |

| that | probably | even she | tomorrow | comes | ||

| 'that even she is probably coming tomorrow.' | ||||||

The examples in (176) show that the singular third person masculine subject pronoun ie'he' is exceptional in that it cannot occur in clause-initial position: it is a truly enclitic pronoun in that it obligatorily follows the complementizer or the finite verb in second position.

| a. | dat-ie | waarschijnlijk | morgen | komt. | embedded clause | |

| that-he | probably | tomorrow | comes | |||

| 'that heʼs probably coming tomorrow.' | ||||||

| b. | Hij/*Ie | komt | waarschijnlijk | morgen. | subject-initial main clause | |

| he/he | comes | probably | tomorrow | |||

| 'Heʼs probably coming tomorrow.' | ||||||

| b'. | Waarschijnlijk | komt-ie | morgen. | other main clauses | |

| probably | comes-he | tomorrow | |||

| 'Probably heʼs coming tomorrow.' | |||||

Example (177) shows that weak subject pronouns differ conspicuously from weak object pronouns in that the latter cannot occur in sentence-initial position.

| a. | Gisteren | heeft | Jan het boek/ʼt | gelezen. | |

| yesterday | has | Jan the book/it | read | ||

| 'Yesterday Jan read the book/it.' | |||||

| b. | Het boek/*ʼt | heeft | Jan gisteren | gelezen. | |

| the book/it | has | Jan yesterday | read |

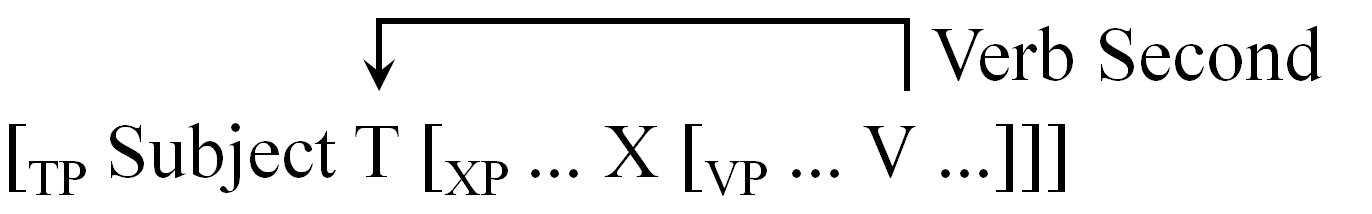

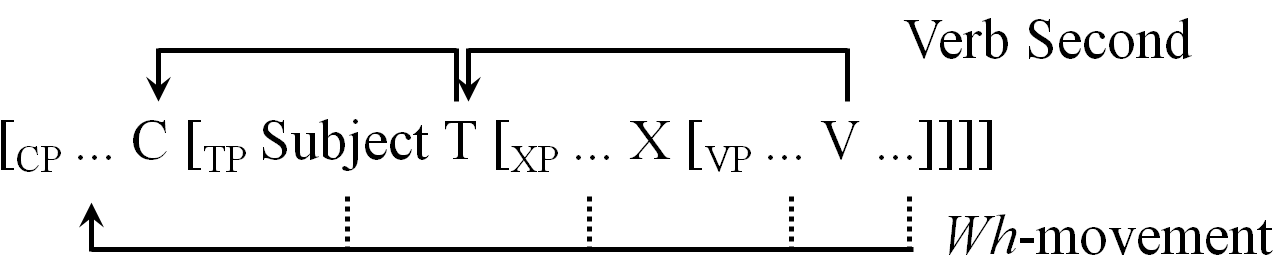

This fact motivated the claim in (178) that subject-initial sentences are not CPs but TPs, as this hypothesis makes it possible to maintain the generalization that weak pronouns cannot be topicalized, that is, wh-moved into the specifier of CP; we refer the reader to Section 9.3 for detailed discussion.

| a. | Subject-initial sentence | |

|

| b. | Other main clauses | |

|

This subsection discusses weak proform shift of object pronouns. In succession, we will address the placement of weak object pronouns with respect to subjects, the relative order of weak direct and indirect object pronouns, and the relative order of weak object pronouns with respect to accusative subjects of AcI-constructions.

Example (177) above has already shown that weak object pronouns cannot occur in sentence-initial position but must occupy a position in the middle field of the clause. The examples in (179) further show that they immediately follow the subject if it is not in sentence-initial position; cf. Huybregts (1991). This does not only hold if the subject is in the regular subject position, as in the primeless examples, but also if it is contrastively focused and can be assumed to be located in the specifier of FocP lower in the clause, as in the primed examples; cf. Section 13.3.2.

| a. | dat | <*ʼt> | Jan/ie <ʼt> | waarschijnlijk <*ʼt> | niet | gelezen | heeft | |

| that | it | Jan/he | probably | not | read | has | ||

| 'that Jan/he probably hasnʼt read it.' | ||||||||

| a'. | dat | <*ʼt> | waarschijnlijk | zelfs Jan <ʼt> | niet | gelezen | heeft. | |

| that | it | probably | even Jan | not | read | has | ||

| 'that even Jan probably hasnʼt read it.' | ||||||||

| b. | dat | <*ʼm> | Marie/ze <ʼm> | waarschijnlijk <*ʼm> | goede raad | wil | geven. | |

| that | him | Marie/she | probably | good advice | wants | give | ||

| 'that Marie/she probably wants to give him good advice.' | ||||||||

| b'. | dat | <*ʼm> | waarschijnlijk | zelfs Marie <ʼm> | goede raad | wil | geven. | |

| that | him | probably | even Marie | good advice | wants | give | ||

| 'that even Marie probably wants to give him good advice.' | ||||||||

In subject-initial main clauses, weak object pronouns immediately follow the finite verb in second position. This is illustrated in (180) by showing that modal adverbs cannot precede the object pronoun but this holds for other constituents as well.

| a. | Jan heeft | <ʼt> | waarschijnlijk <*ʼt> | niet | gelezen. | |

| Jan has | it | probably | not | read | ||

| 'Jan probably hasnʼt read it.' | ||||||

| b. | Marie wil | <ʼm> | waarschijnlijk <*ʼm> | goede raad | geven. | |

| Marie wants | him | probably | good advice | give | ||

| 'Marie probably wants to give him good advice.' | ||||||

The previous subsection has shown that weak proform shift cannot affect the unmarked order of the subject and the objects. This is different when it comes to the relative order of direct and indirect objects: while direct objects normally follow nominal indirect objects under a neutral intonation pattern, weak pronominal direct objects normally precede indirect objects. Example (181b) shows that this holds regardless of whether the indirect object is non-pronominal or pronominal. It should further be noted that it also holds if the two object pronouns have the same form: the first object pronoun in dat Peter ʼm ʼm aanbood'that Peter offered it to him' is construed as the direct object.

| a. | dat | Peter | <*de auto> | Marie | <de auto> | aanbood. | |

| that | Peter | the car | Marie | the car | prt.-offered | ||

| 'that Peter offered Marie the car.' | |||||||

| b. | dat | Peter | <ʼm> | Marie/ʼr <??ʼm> | aanbood. | |

| that | Peter | him | Marie/her | prt.-offered | ||

| 'that Peter offered it to Marie/her.' | ||||||

Weak objects pronouns are always adjacent to each other, which may be due to the fact illustrated in the previous subsection that they must both be adjacent to the finite verb or the subject if it is not in clause-initial position; the only new thing is that this restriction does not hold for the individual pronouns but for the full cluster. It should also be noted that Haegeman (1993a) observes for W-Flemish that inversion of the indirect and direct object requires the indirect object to be scrambled. Example (182) shows that the same seems to hold in Dutch, although it should be noted that the degraded order improves if the indirect object is assigned contrastive accent.

| dat | Jan | ʼt | <Marie> | waarschijnlijk <*?Marie> | gegeven | heeft. | ||

| that | Jan | it | Marie | probably | given | has | ||

| 'that Jan has probably given it to Marie.' | ||||||||

This reversal of the direct and the indirect objects is possible only with reduced direct objects. It is not easy, however, to demonstrate reversal for strong referential personal pronouns because they cannot be used to refer to inanimate entities. The examples in (183) therefore illustrate this reversal by means of the demonstrative die'that one'; the judgments only hold under a non-contrastive intonation pattern.

| a. | dat | Peter | <??die> | Marie <die> | aanbood. | |

| that | Peter | dem | Marie | prt.-offered | ||

| 'that Peter offered Marie that one.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Peter | <*die> | ʼr <die> | aanbood. | |

| that | Peter | dem | her | prt.-offered | ||

| 'that Peter offered her that one.' | ||||||

The fact that object pronouns can be inverted while non-pronominal nominal arguments cannot has given rise to the hypothesis that they do not occupy the same position in the middle field of the clause, since only weak pronouns undergo weak proform shift; cf. Zwart (1996). If we assume in addition that weak proform shift is similar to clitic movement in languages like French, this hypothesis can be supported by the fact that third person direct and indirect object clitics in French appear in the same order as in Dutch: Jean leDO luiIO donnera'Jean will give it to him/her'. The fact discussed earlier that weak object pronouns cluster provides additional support to the hypothesis that they are clitic-like.

Subjects and direct objects of infinitival complement clauses in AcI-constructions are indistinguishable as far as their morphological form is concerned: this holds not only for referential noun phrases but also for their pronominalized counterparts, as both appear as object pronouns. Nevertheless, the examples in (184a&b) show that weak proform shift of an embedded object can optionally cross the subject of the infinitival clause; cf. Zwart (1996). Example (184c) shows that this is in fact the preferred option if the subject is also realized as a weak pronoun. The acceptability of inversion shows that the restriction established above, namely that weak proform shift of objects cannot affect the unmarked order of subjects and objects, only holds if the subject is assigned nominative case.

| a. | Jan zag/liet | <*het boektheme> | Marieagent < het boektheme> | lezen. | |

| Jan saw/let | the book | Marie | read | ||

| 'Jan saw/let Marie read the book.' | |||||

| b. | Jan zag/liet | <ʼttheme> | Marieagent <ʼttheme> | lezen. | |

| Jan saw/let | it | Marie | read |

| c. | Jan zag/liet | <ʼttheme> | ʼragent <??ʼttheme> | lezen. | |

| Jan saw/let | it | her | read |

The examples in (185) show that weak proform shift of an embedded direct object may also cross the subject if the infinitival clause is ditransitive: the direct object pronoun must cross the indirect object and optionally crosses the embedded subject.

| a. | Jan zag/liet | <*het boektheme> | Elsagent | Petergoal <het boektheme> | aanbieden. | |

| Jan saw/let | the book | Els | Peter | prt. offer | ||

| 'Jan saw/let Els offer Peter the book.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan zag/liet | <ʼttheme> | Elsagent <ʼttheme> Petergoal | <??ttheme> | aanbieden. | |

| Jan saw/let | it | Els | Peter | prt.-offer |

It seems, however that weak embedded indirect object pronouns cannot cross the subject of the infinitival clause: according to us, (186b) can only be interpreted with the pronoun as an agent and Els as a goal. It seems plausible that the deviance of (186b) is related to the fact that the agent and the goal are both +human.

| a. | Jan zag/liet | <*Petergoal> | Elsagent <Petergoal> | het boektheme | aanbieden. | |

| Jan saw/let | Peter | Els | the book | prt. offer | ||

| 'Jan saw/let Els offer Peter the book.' | ||||||

| b. | * | Jan zag/liet | <ʼmgoal> | Elsagent <ʼmgoal> | het boektheme | aanbieden. |

| Jan saw/let | him | Els | the book | prt. offer | ||

| 'Jan saw/let Els offer him the book.' | ||||||

Something similar holds for cases in which both the direct and the indirect object surface as weak pronouns: examples such as (187b), which are given as fully acceptable in Zwart (1993/1996), are only acceptable to us if the pronoun ʼm is interpreted as agent and Els as goal. The unacceptability of (187c) deserves special mention as it is unexpected in the light of the fact that (184c) is fully acceptable; the fact that weak object pronouns must be adjacent to each other again provides support to the hypothesis that they are clitic-like in that they obligatorily cluster.

| a. | Jan zag/liet | Elsagent | ʼttheme | ʼmgoal | aanbieden. | |

| Jan saw/let | Els | it | him | prt. offer | ||

| 'Jan saw/let Els offer it to him.' | ||||||

| b. | * | Jan zag/liet | ʼttheme | ʼmgoal | Elsagent | aanbieden. |

| Jan saw/let | it | him | Els | prt. offer |

| c. | * | Jan zag/liet | ʼttheme | Elsagent | ʼmgoal | aanbieden. |

| Jan saw/let | it | Els | him | prt. offer |

Example (188a) shows that if all the arguments of a ditransitive infinitival clause surface as weak pronouns they must occur in the order agent > theme > goal. It should be pointed out, however, that some speakers find a sequence of three weak pronouns difficult to pronounce and may therefore prefer the version in (188b) with a prepositional indirect object; in such cases the theme again preferably precedes the agent.

| a. | Jan zag/liet | ʼragent | ʼttheme | ʼmgoal | aanbieden. | |

| Jan saw/let | her | it | him | prt. offer | ||

| 'Jan saw/let her offer him the book.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan zag/liet | <ʼttheme> | ʼragent <ʼttheme> | aan ʼmgoal | aanbieden. | |

| Jan saw/let | it her | her | to him | prt. offer | ||

| 'Jan saw/let her offer it to him.' | ||||||

Example (189) suggests that weak proform shift is able to feed binding: while non-pronominal direct objects cannot bind a reciprocal indirect object, shifted direct object pronouns can.

| dat | Marie | <zetheme> | elkaargoal | <*de jongenstheme> | voorgesteld | heeft. | ||

| that | Marie | them | each.other | the boys | prt.-introduced | has | ||

| 'that Marie has introduced them to each other.' | ||||||||

Since feeding of binding is generally seen as a hallmark of A-movement, this may also suggest that weak proform shift is A-movement. It should be noted, however, that weak proform shift may be preceded by nominal argument shift and that it may be the case that this is responsible for feeding binding; cf. Haegeman (1993a/1993b). We provisionally assume that weak proform shift of arguments is A'-movement because Subsection III will show that weak proforms that do not function as arguments may undergo a similar shift.

Section 2.1.2 has shown that derived subjects can either precede or follow an indirect object; this is illustrated again in (190a) by means of the passivized counterpart of the ditransitive construction dat Jan Peter/ʼm de baan aanbood 'that Jan offered Peter/him the job' . Example (190b) shows that the weak subject pronoun must precede the indirect object (which is not very surprising because strong subject pronouns are obligatorily moved into the regular subject position by nominal argument object shift; see 13.2, sub IB). The examples in (191) show the same for the dyadic unaccusative (nom-dat) verb bevallen 'to please' .

| a. | dat | <de baan> | Peter/ʼm <de baan> | aangeboden | werd. | |

| that | the job | Peter/him | prt.-offered | was | ||

| 'that the job was offered to Peter/him.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | <ie> | Peter/ʼm | <*ie> | aangeboden | werd. | |

| that | he | Peter/him | he | prt.-offered | was | ||

| 'that it was offered to Peter/him.' | |||||||

| a. | dat | <de film> | Peter/ʼm <de film> | bevallen | is. | |

| that | the movie | Peter/him | pleased | is | ||

| 'that the movie has pleased Peter/him.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | <ie> | Peter/ʼm | <*ie> | bevallen | is. | |

| that | he | Peter/him | he | pleased | is | ||

| 'that it has pleased Peter/him.' | |||||||

The previous subsections have shown that weak object pronouns cannot be moved across nominative subjects. At first sight, this would suggest that weak proform shift cannot affect the unmarked order of nominal arguments (agent > goal > theme), but this turns out not to be correct, as is clear from the fact that weak direct object pronouns preferably precede nominal indirect objects, and that they can also be moved across an embedded subject in an AcI-construction. That weak proform shift can affect the unmarked order of nominal argument shows that weak pronouns can occupy positions in the clause that are not accessible to their non-pronominal counterparts, which in turn gives credence to the hypothesis that they are clitic-like. This hypothesis is further supported by the fact that weak object pronouns obligatorily cluster together.

Weak subject and object pronouns exhibit various properties often attributed to clitics. The examples in (192) show, for example, that they cannot be used as independent utterances and cannot be topicalized or coordinated; see Haegeman (1993b) for relevant discussion. Zwart (1996) notes, however, that these properties also hold for the English reduced pronouns, which behave syntactically as regular pronouns, and concludes from this that they are not defining characteristics of clitics but simply follow from the fact that weak pronouns cannot be accented.

| a. | Wie | heb | je | gezien? | Hem/*ʼm. | |

| who | have | you | seen | him/him |

| b. | Hem/*ʼm | heb | ik | niet | gezien. | |

| him/him | have | I | not | seen | ||

| 'Him, I havenʼt seen.' | ||||||

| c. | [hem | en | haar]/ | *[ʼm | en | ʼr] | |

| him | and | her | him | and | her |

A potential problem for the claim that Dutch weak pronouns are clitics is that they differ from run-of-the-mill clitics in that they are not hosted by a verb. A related problem is that they can occur in PPs: bij ʼm'with him'; cf. Haegeman (1993b). The hypothesis that Dutch weak pronouns are clitics thus requires there to be some (phonetically empty) functional head that they can cliticize to. Currently, there does not seem to be a generally accepted analysis available but the tentative proposals in Haegeman (1993a/1993b) and Zwart (1993/1996) do agree on the fact that the prospective functional head(s) have nominal (case or agreement) features. We leave this claim for future research.

Section N5.2.1.5 has shown that Dutch has two types of reflexive pronouns: simplex reflexive pronouns such as third person zich and complex ones such as third person zichzelf'him/herself/themselves'. Simplex reflexive pronouns differ from complex ones in that they must precede modal adverbs such as waarschijnlijk'probably'; cf. Huybregts (1991). We refer the reader to N5.2.1.5 for a more extensive discussion of these two forms.

| a. | Marie heeft | <zichzelf> | waarschijnlijk <zichzelf> | aan Jan | voorgesteld. | |

| Marie has | herself | probably | to Jan | prt.-introduced | ||

| 'Marie has probably introduced herself to Jan' | ||||||

| b. | Marie heeft | <zich> | waarschijnlijk <*zich> | voorgesteld | aan Jan. | |

| Marie has | refl | probably | prt.-introduced | to Jan | ||

| 'Marie has probably introduced herself to Jan.' | ||||||

Simplex reflexive pronouns behave like object pronouns in that they cannot precede subject pronouns. We illustrate this in (194) by means of a number of strong singular referential personal pronouns; the judgments do not change if we replace the strong subject pronouns by their weak counterparts.

| a. | dat | <*me> | ik <me> | nog | niet | heb | voorgesteld. | |

| that | refl | I | yet | not | have | prt.-introduced | ||

| 'that I havenʼt introduced myself yet.' | ||||||||

| b. | dat | <*je> | jij <je> | nog | niet | hebt | voorgesteld. | |

| that | refl | you | yet | not | have | prt.-introduced | ||

| 'that you havenʼt introduced yourself yet.' | ||||||||

| c. | dat | <*zich> | zij <zich> | nog | niet | heeft | voorgesteld. | |

| that | refl | she | yet | not | has | prt.-introduced | ||

| 'that she hasnʼt introduced herself yet.' | ||||||||

Simplex reflexive pronouns are special, however, in that they normally precede non-specific indefinite and negative subject pronouns, which we illustrate in (195) by means of expletive- there constructions; cf. Haeseryn et al. (1997:1314). This means that they differ from object pronouns, which can never be moved across the subject of their clause but instead push the subject up into the regular subject position: see Section 13.2, sub IC1, for discussion.

| a. | dat | er | <zich> | drie vaten bier <*zich> | in de kelder bevinden. | |

| that | there | refl | three barrels [of] beer | in the cellar are.located | ||

| 'There are three barrels of beer in the cellar.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | er | <zich> | een meisje <*zich> | in de kelder | opgehangen | heeft. | |

| that | there | refl | a girl | in the cellar | prt.-hanged | has | ||

| 'that a girl has hanged herself in the cellar.' | ||||||||

With respect to specific indefinite and generic subject pronouns simplex reflexive pronouns again behave like object pronouns in that they follow them; cf. Haeseryn et al. (1997:1314).

| a. | dat | <*zich> | een vriendin van hem <zich> | in de kelder | opgehangen | heeft. | |

| that | refl | a friend of him | in the cellar | prt.-hanged | has | ||

| 'that a lady friend of his has hanged herself in the cellar.' | |||||||

| b. | dat | <*zich> | een puber <zich> | nu | eenmaal | zo | gedraagt. | |

| that | refl | an adolescent | prt | prt | like.that | behaves | ||

| 'that an adolescent will behave like that.' | ||||||||

The ordering with respect to definite subjects seems to be relatively free, as is clear from example (197b). The placement of the subject in this example seems to be determined by the information structure of the clause: it follows the reflexive if it is part of the new information of the clause, while it precedes the reflexive if it is part of the presupposition; cf. Haeseryn et al. (1997:1315).

| a. | dat | er | zich | hier | een drama | heeft | afgespeeld. | |

| that | there | refl | here | a tragedy | has | prt.-played | ||

| 'that a tragedy took place here.' | ||||||||

| b. | dat <dat drama> zich | hier <dat drama> | afgespeeld | heeft. | |

| that that tragedy refl | here | prt.-played | has | ||

| 'that that tragedy took place here.' | |||||

This is consistent with the observation in Haeseryn et al. that the order reflexive–subject is found especially with inherently reflexive predicates that denote a process of appearing or coming into existence. Some examples are given in (198).

| a. | In de verte | verhieven | zich | de Alpen. | |

| in the distance | rose | refl | the Alps | ||

| 'In the distance rose the Alps.' | |||||

| b. | Er | dienen | zich | twee problemen | aan. | |

| there | present | refl | two problems | prt. | ||

| 'Two problems present themselves.' | ||||||

| c. | Er | tekende | zich | een kleine meerderheid | af. | |

| there | silhouetted | refl | a small majority | prt. | ||

| 'A small majority became apparent.' | ||||||

The ordering vis-a-vis negative subjects also has a semantic effect: while (199) expresses that there are no registrations at all, example (199b) does not necessarily imply this but may also be used to express that no individual from a contextually defined set has registered; cf. Haeseryn et al. (1997:1315).

| a. | dat | zich | nog | niemand | heeft | aangemeld. | |

| that | refl | yet | nobody | has | prt.-registered | ||

| 'that nobody has registered yet.' | |||||||

| b. | dat | niemand | zich | nog | heeft | aangemeld. | |

| that | nobody | refl | yet | has | prt.-registered | ||

| 'that nobody has registered yet.' | |||||||

In some cases it is virtually impossible for the reflexive pronoun to precede the subject; in (200) the simplex reflexive must follow the negative subject even though this means that it cannot be shifted across the modal adverb; cf. (193b). The acceptability contrast indicated is confirmed by the fact that a Google search (7/14/2015) on the string [zich niemand herinnert] resulted in no more than five relevant examples from the 19th century, while the alternative order resulted in 48 hits. It is not yet clear what determines precisely whether the order reflexive pronoun–subject is possible or not, although it is conspicuous that all examples given in Haeseryn et al. (1997) involve intransitive inherently reflexive verbs.

| a. | dat | (waarschijnlijk) | niemand | zich | die man | herinnert. | |

| that | probably | nobody | refl | that man | remembers | ||

| 'that probably nobody remembers that man.' | |||||||

| b. | ?? | dat | zich | (waarschijnlijk) | niemand | die man | herinnert. |

| that | refl | probably | nobody | that man | remembers |

In transitive constructions, the relative order of weak object and simplex reflexive pronouns seems to be relatively free, although there is a clear preference for the former to precede the latter. We checked this for the pronoun het'it', which is virtually always weak in speech, by doing a Google search (7/14/2015) on the search strings [het zich (niet) herinnert] and [zich het (niet) herinnert].

| a. | dat | Jan | ʼt | zich | (niet) | herinnert. | 207 hits | |

| that | Jan | it | refl | not | remembers | |||

| 'that Jan remembers it/that Jan doesnʼt remember it.' | ||||||||

| b. | dat | Jan | zich | ʼt | (niet) | herinnert. | 36 hits | |

| that | Jan | refl | it | not | remembers | |||

| 'that Jan remembers it/that Jan doesnʼt remember it.' | ||||||||

For completeness’ sake, it should be noted that the preferred Dutch order differs from the one found in French, where the reflexive clitic precedes the object clitic: cf. Il se le rappelle'He remembers it'.

The phonetically weak R-word er has the four distinctive functions illustrated in (202). Expletive er normally introduces some indefinite subject (cf. N8.1.4) but also occurs in impersonal passives (cf. 3.2.1.2), locational er refers to some contextually defined location, prepositional er represents the nominal part of a pronominalized PP (cf. P5), and quantitative er is associated with an interpretative gap [e] in a quantified noun phrase (cf. N6.3). Sometimes a single occurrence of er expresses more than one function, but this will be ignored here; see Section P5.5 for extensive discussion.

| a. | dat | <er> | waarschijnlijk <*er> | iemand | ziek | is. | expletive | |

| that | there | probably | someone | ill | is | |||

| 'that there is probably someone ill.' | ||||||||

| b. | dat | Jan | <er> | waarschijnlijk <*er> | geweest | is. | locational | |

| that | Jan | there | probably | been | is | |||

| 'that Jan has probably been there.' | ||||||||

| c. | dat | Jan <er> | waarschijnlijk <?er> | over | wil | praten. | prepositional | |

| that | Jan there | probably | about | wants | talk | |||

| 'that Jan probably wants to talk about it.' | ||||||||

| d. | dat | Jan <eri> | waarschijnlijk <*eri> | [twee/veel [ei]] | heeft. | quantitative | |

| that | Jan there | probably | two/many | has | |||

| 'that Jan probably has two/many of them.' | |||||||

This subsection will focus on the distribution of the various types within the clause. The examples in (202) already show that all types resemble weak pronouns in that they normally precede modal adverbs such as waarschijnlijk'probably'. Details concerning their placement will be discussed in separate subsections.

The distribution of expletive er is identical to that of (weak) subject pronouns: in main clauses it immediately precedes or follows the finite verb and in embedded clauses it immediately follows the complementizer (if overtly realized). It is therefore not surprising that it is often assumed that expletive er is located in the regular subject position, that is, the specifier of TP. Putting aside cases in which expletive er occupies the sentence-initial position, this correctly predicts that it is always the leftmost element in the middle field of the clause.

| a. | Er | komt | morgen | waarschijnlijk | een vriend van hem | op visite. | |

| there | comes | tomorrow | probably | a friend of his | on visit | ||

| 'There is probably a friend of his coming to visit us tomorrow.' | |||||||

| a'. | Morgen | komt | er | waarschijnlijk | een vriend van hem | op visite. | |

| tomorrow | comes | there | probably | a friend of his | on visit | ||

| 'Tomorrow there is probably a friend of his coming to visit us.' | |||||||

| b. | dat | er | morgen | waarschijnlijk | een vriend van hem | op visite | komt. | |

| that | there | tomorrow | probably | a friend of his | on visit | comes | ||

| 'that there is probably a friend of his coming to visit us tomorrow.' | ||||||||

Locational er differs from other locational proforms in that it must precede the modal adverbs. The (a)-examples in (204) illustrate this for an adverbial phrase, and the (b)-examples for a complementive. Observe that the locational R-word daar can also be moved across the modal adverb; we return to this in Subsection C.

| a. | dat | Jan waarschijnlijk | in de speeltuin | speelt. | adverbial | |

| that | Jan probably | in the playground | plays | |||

| 'that Jan is probably playing in the playground.' | ||||||

| a'. | dat | Jan <daar/er> | waarschijnlijk <daar/*er> | speelt. | |

| that | Jan there/there | probably | plays | ||

| 'that Jan is probably playing there.' | |||||

| b. | dat | Jan waarschijnlijk | in de speeltuin | geweest | is. | complementive | |

| that | Jan probably | in the playground | been | is | |||

| 'that Jan has probably been in the playground.' | |||||||

| b'. | dat | Jan <daar/er> | waarschijnlijk <daar/*er> | geweest | is. | |

| that | Jan there/there | probably | been | is | ||

| 'that Jan has probably been there.' | ||||||

The examples in (205) show that location er resembles the French locative clitic y in that it follows weak object pronouns: cf. Je les y ai vus'I have seen them there'.

| a. | dat | ik | ze | er | gezien heb. | |

| that | I | them | there | seen have | ||

| 'that I have seen them there.' | ||||||

| b. | * | dat | ik | er | ze | gezien | heb. |

| that | I | there | them | seen | have |

Pronominal PPs functioning as an argument of the verb can be split; movement of heavier R-words such as daar is optional, while movement of the weak form er is greatly preferred. The two parts of the pronominal PP are in italics.

| a. | dat | Jan waarschijnlijk | over dat probleem | wil | praten. | |

| that | Jan probably | about that problem | wants | talk | ||

| 'that Jan probably wants to talk about that problem.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Jan | <daar> | waarschijnlijk [PP <daar> | over] | wil | praten. | |

| that | Jan | there | probably | about | wants | talk | ||

| 'that Jan probably wants to talk about that.' | ||||||||

| c. | dat | Jan <er> | waarschijnlijk [PP <?er> | over] | wil | praten. | |

| that | Jan there | probably | about | wants | talk | ||

| 'that Jan probably wants to talk about it.' | |||||||

The fact that daar and er can both be moved leftward, which was also observed in the previous subsection for locational proforms, can perhaps be taken as evidence against the claim that er is clitic-like by assuming that the ability to undergo leftward movement is simply a more general property of R-words. Indeed, it has been suggested that there is a designated [+R]-position in the functional domain of the clause that serves as a landing site for R-words; cf. Van Riemsdijk (1978). The examples in (207) show, however, that it is possible to shift two R-words in a single clause as long as they are not both weak or both strong.

| a. | dat | Jan | er | hier | waarschijnlijk | niet | over | wil praten. | |

| that | Jan | there | here | probably | not | about | wants talk | ||

| 'that Jan probably doesnʼt want to talk about it here.' | |||||||||

| b. | * | dat | Jan | er | er | waarschijnlijk | niet | over | wil praten |

| that | Jan | there | there | probably | not | about | wants talk | ||

| 'that Jan probably doesnʼt want to talk about it here.' | |||||||||

| c. | ?? | dat | Jan | daar | hier | waarschijnlijk | niet | over | wil | praten. |

| that | Jan | there | here | probably | not | about | wants | talk | ||

| 'that Jan probably doesnʼt want to talk about it here.' | ||||||||||

Huybregts (1991) concluded from this that there are actually two [+R]-positions, one of which is accessible to weak R-words only. If correct, this shows that it is possible to identify a designated position for the weak R-word er after all, as required by the hypothesis that er is clitic-like. We will not digress on this here, but refer to reader to Section P5.5 for a detailed discussion of Huybregts’ proposal.

The examples in (208) show that while prepositional er is able to precede non-pronominal objects, it must follow weak object pronouns.

| a. | Jan heeft | zijn kinderen | tegen | ongewenste invloeden | beschermd. | |

| Jan has | his children | against | undesirable influences | protected | ||

| 'Jan has protected his children against undesirable influences.' | ||||||

| a'. | Jan heeft | <er> zijn kinderen <er> | tegen | beschermd. | |

| Jan has | there his children | against | protected | ||

| 'Jan has protected his children against them.' | |||||

| a''. | Jan heeft | <*er> | ze <er> | tegen beschermd. | |

| Jan has | there | them | against protected |

| b. | Marie heeft | Peter | tot | diefstal | gedwongen. | |

| Marie has | Peter | to | theft | forced | ||

| 'Marie has forced Peter to steal.' | ||||||

| b'. | Marie heeft | <er> | Peter <er> | toe | gedwongen. | |

| Marie has | there | Peter | to | forced | ||

| 'Marie has forced Peter to do it.' | ||||||

| b''. | Marie heeft | <*er> | ʼm <er> | toe | gedwongen. | |

| Marie has | there | him | to | forced |

Quantitative er is associated with an interpretative gap within a quantified nominal argument which can be filled in on the basis of contextual information. While Peter is looking for a pan, the speaker may tell him how to obtain one by means of the utterances in (209a&b). Example (209c) likewise implies that there is a contextually defined set of individuals (say, students) who are given a book.

| a. | Er | staan | eri | waarschijnlijk [NP | twee [ei]] | in de keuken. | subject | |

| there | stand | there | probably | two | in the kitchen | |||

| 'There are probably two [pans] in the kitchen.' | ||||||||

| b. | Jan heeft | eri | waarschijnlijk [NP | drie [ei]] | op tafel | gezet. | direct object | |

| Jan has | there | probably | three | on table | put | |||

| 'Jan has put three [pans] on the table.' | ||||||||

| c. | Jan gaf | eri | waarschijnlijk [NP | één [ei]] | een boek. | indirect object | |

| Jan gave | there | probably | one | a book | |||

| 'Jan probably gave one [student] a book.' | |||||||

The examples in (209) show that quantitative er is obligatorily placed in front of the modal adverb and follows the finite verb in subject-initial clauses. If the subject is located in the middle field. as in (210), quantitative er follows the subject even if the subject follows a modal adverb.

| a. | dat | Jan eri | waarschijnlijk [NP | één [ei]] | heeft. | |

| that | Jan there | probably | one | has | ||

| 'that Jan probably has one.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | waarschijnlijk | niemand | eri [NP | één [ei]] | heeft. | |

| that | probably | nobody | there | one | has | ||

| 'that probably nobody has one.' | |||||||

When we consider the relative order of quantitative er and weak object pronouns, at least three cases should be distinguished; this will be discussed in the following subsections.

If the associate of quantitative er is a subject, a weak direct object pronoun must follow the associate, and even then the result is somewhat marked, which we indicate here by means of a question mark. This is shown in (211b), on the basis of the clause dat vier studenten het boek gelezen hebben'that four students have read the book.'

| a. | dat | eri [NP | vier [ei]] | het boek | gelezen | hebben. | |

| that | there | four | the book | read | have |

| b. | dat | <*ʼt> | eri <*ʼt> [NP | vier [ei]] < ?ʼt> | gelezen | hebben. | |

| that | it | there | four | read | have |

Example (212b) shows that the same holds for weak indirect object pronouns, on the basis of the clause dat twee studenten Peter het boek aangeboden hebben'that two students have offered Peter the book'. For completeness’ sake, the (c)-examples show that the direct and indirect pronouns must appear after the associate; although the primeless (c)-example is somewhat marked itself, the contrast with the primed ones is quite sharp.

| a. | dat | eri [NP | twee [ei]] | Peter | het boek | aangeboden | hebben. | |

| that | there | two | Peter | the book | prt.-offered | have |

| b. | dat | eri | <*ʼm> [NP | twee [ei]] < ?ʼm> | het boek | aangeboden | hebben. | |

| that | there | him | two | the book | prt.-offered | have |

| c. | ? | dat | eri [NP | twee [ei]] | ʼt | ʼm | aangeboden | hebben. |

| that | there | two | it | him | prt.-offered | have |

| c'. | * | dat | eri | ʼt [NP | twee [ei]] | ʼm | aangeboden | hebben. |

| that | there | it | two | him | prt.-offered | have |

| c''. | * | dat | eri | ʼt | ʼm [NP | twee [ei]] | aangeboden | hebben. |

| that | there | it | him | two | prt.-offered | have |

Example (213a) shows that quantitative er may either precede or follow the indirect object. This is not entirely optional, however, as the (b)-examples bear out that the choice is partly determined by the surface position of the indirect object. Example (213b) shows that if the indirect object surfaces after the modal verb, the shift of quantitative er is indeed optional, although it should be noted that the shift must cross the modal adverb. Example (213c) shows that if the indirect object has undergone nominal argument shift, weak proform shift must apply as well although it may end up either preceding or following the indirect object.

| a. | Marie heeft | <eri> | Jan <eri> [NP | één [ei]] | gegeven. | |

| Marie has | there | Jan | one | given | ||

| 'Marie has given Jan one.' | ||||||

| b. | Marie heeft | <eri> | waarschijnlijk <*er> | Jan <eri> [NP | één [ei]] | gegeven. | |

| Marie has | there | probably | Jan | one | given |

| c. | Marie heeft | <eri> | Jan <eri> | waarschijnlijk <*eri> [NP | één [ei]] | gegeven. | |

| Marie has | there | Jan | probably | one | given |

While the examples in (213) show that quantitative er may either precede or follow a non-pronominal indirect object, there may be a preference for it to follow weak indirect object pronouns, although Haeseryn et al. (1997:1321) take both orders to be fully acceptable; note that the /d/ in (214b) is a linking sound that is inserted to break the sequence of two schwa’s. If this preference is indeed significant, we should conclude that quantitative er behaves similarly in this respect to the French partitive clitic en: cf. Je lui en ai donné une'I have given him one'.

| a. | Jan heeft | <?eri> | ʼm <eri> [NP | één [ei]] | gegeven. | |

| Jan has | there | him | one | given | ||

| 'Jan has given him one.' | ||||||

| b. | Ik | heb | <?eri> | ze <(d)eri> [NP | een paar [ei]] | gegeven. | |

| I | have | there | them | a couple | given | ||

| 'Iʼve given them a couple.' | |||||||

It is hard to construct cases with a weak indirect object pronoun. It seems that the pronoun preferably precedes quantitative er. We illustrate this in (215) for the sentence dat ik twee studenten het boek heb aangeboden'that I have offered the book to two students'.

| a. | dat | ik | eri [NP | twee [ei]] | het boek | heb | aangeboden | |

| that | I | there | two | the book | have | prt.-offered |

| b. | ?? | dat | ik | eri [NP | twee [ei]] | ʼt | heb | aangeboden. |

| that | I | there | two | it | have | prt.-offered |

| b'. | * | dat | ik | eri | ʼt [NP | twee [ei]] | heb | aangeboden. |

| that | I | there | it | two | have | prt.-offered |

| b''. | ? | dat | ik | ʼt | eri [NP | twee [ei]] | heb | aangeboden. |

| that | I | it | there | two | have | prt.-offered |

The previous subsections have shown that there are grounds for assuming that weak proforms are clitic-like. The first and foremost reason is that weak proforms are like clitics in that they cluster together. Furthermore, there are certain similarities in the relative order of weak proforms and, e.g., French clitics. This holds especially for weak object pronouns. First, weak proform shift inverts the order of third person indirect and direct objects, just like clitic placement in French. Second, weak object pronouns precede most other weak proforms, as do the object clitics in French. The only difference involves the reflexive forms: reflexive clitics precede object clitics while simplex reflexive zich tends to follow the weak object pronouns. Another reason not yet mentioned is that weak proform shift is clause-bound: it is never possible to move a weak proform out of its minimal finite clause (cf. Huybregts 1991). A conspicuous difference between clitics and weak proforms is that the former normally attach to a verbal host while the latter do not: with the exception of the simplex reflexive zich the Dutch proforms must follow the (nominative) subject. It should also be noted that the location of the subject is immaterial:

| a. | dat | Jan ʼt | waarschijnlijk | gekocht | heeft. | |

| that | Jan it | probably | bought | has | ||

| 'that Jan has probably bought it.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | <*ʼt> | waarschijnlijk | Jan <ʼt> | gekocht | heeft | |

| that | it | probably | Jan | bought | has | ||

| 'that Jan has probably bought it.' | |||||||

| b'. | dat | <*ʼt> | waarschijnlijk | niemand <ʼt> | gekocht | heeft | |

| that | it | probably | nobody | bought | has | ||

| 'that probably nobody has bought it.' | |||||||

If we adopt the conclusions from Section 13.2 and 13.3.1 that the subjects in the examples in (216) occupy different positions, we must conclude that there is no fixed target position for weak proform shift either, which may be a potential problem for claiming that weak proform shift and clitic placement are virtually the same operation. We leave this issue to future research.

- 1993The morphology and distribution of object clitics in West FlemishStudia Linguistica4757-94

- 1993Some Speculations on Argument Shift, Clitics and Crossing in West-FlemishAbraham, Werner & Bayer, Josef (eds.)Dialektsyntax (Linguistische Berichte Sonderheft 6OpladenWestdeutscher Verlag131-160

- 1993The morphology and distribution of object clitics in West FlemishStudia Linguistica4757-94

- 1993The morphology and distribution of object clitics in West FlemishStudia Linguistica4757-94

- 1993Some Speculations on Argument Shift, Clitics and Crossing in West-FlemishAbraham, Werner & Bayer, Josef (eds.)Dialektsyntax (Linguistische Berichte Sonderheft 6OpladenWestdeutscher Verlag131-160

- 1993Some Speculations on Argument Shift, Clitics and Crossing in West-FlemishAbraham, Werner & Bayer, Josef (eds.)Dialektsyntax (Linguistische Berichte Sonderheft 6OpladenWestdeutscher Verlag131-160

- 1993Some Speculations on Argument Shift, Clitics and Crossing in West-FlemishAbraham, Werner & Bayer, Josef (eds.)Dialektsyntax (Linguistische Berichte Sonderheft 6OpladenWestdeutscher Verlag131-160

- 1993The morphology and distribution of object clitics in West FlemishStudia Linguistica4757-94

- 1993Some Speculations on Argument Shift, Clitics and Crossing in West-FlemishAbraham, Werner & Bayer, Josef (eds.)Dialektsyntax (Linguistische Berichte Sonderheft 6OpladenWestdeutscher Verlag131-160

- 1997Algemene Nederlandse spraakkunstGroningenNijhoff

- 1997Algemene Nederlandse spraakkunstGroningenNijhoff

- 1997Algemene Nederlandse spraakkunstGroningenNijhoff

- 1997Algemene Nederlandse spraakkunstGroningenNijhoff

- 1997Algemene Nederlandse spraakkunstGroningenNijhoff

- 1997Algemene Nederlandse spraakkunstGroningenNijhoff

- 1991CliticsModel, Jan (ed.)Grammatische analyseDordrechtICG Printing

- 1991CliticsModel, Jan (ed.)Grammatische analyseDordrechtICG Printing

- 1991CliticsModel, Jan (ed.)Grammatische analyseDordrechtICG Printing

- 1991CliticsModel, Jan (ed.)Grammatische analyseDordrechtICG Printing

- 1991CliticsModel, Jan (ed.)Grammatische analyseDordrechtICG Printing

- 1961Persoonsvorm en voegwoordDe Nieuwe Taalgids54296-301

- 1978A case study in syntactic markedness: the binding nature of prepositional phrasesnullnullnullPeter de Ridder Press

- 1993Dutch syntax. A minimalist approachGroningenUniversity of GroningenThesis

- 1993Dutch syntax. A minimalist approachGroningenUniversity of GroningenThesis

- 1993Dutch syntax. A minimalist approachGroningenUniversity of GroningenThesis

- 1996Clitics, Scrambling, and Head Movement in DutchHalpern, Aaron L. & Zwicky, Arnold M. (eds.)Approaching second. Second position clitics and related phenomenaStanfordCSLI579-611

- 1996Clitics, Scrambling, and Head Movement in DutchHalpern, Aaron L. & Zwicky, Arnold M. (eds.)Approaching second. Second position clitics and related phenomenaStanfordCSLI579-611

- 1996Clitics, Scrambling, and Head Movement in DutchHalpern, Aaron L. & Zwicky, Arnold M. (eds.)Approaching second. Second position clitics and related phenomenaStanfordCSLI579-611

- 1996Clitics, Scrambling, and Head Movement in DutchHalpern, Aaron L. & Zwicky, Arnold M. (eds.)Approaching second. Second position clitics and related phenomenaStanfordCSLI579-611

- 1996Clitics, Scrambling, and Head Movement in DutchHalpern, Aaron L. & Zwicky, Arnold M. (eds.)Approaching second. Second position clitics and related phenomenaStanfordCSLI579-611

- 1996Clitics, Scrambling, and Head Movement in DutchHalpern, Aaron L. & Zwicky, Arnold M. (eds.)Approaching second. Second position clitics and related phenomenaStanfordCSLI579-611